Building an Early Learning System that Works: Next Steps for California

Summary

This brief provides California policymakers with recommendations on how to improve access to high-quality early childhood education (ECE) for all children. It is based on a report that examines the ECE practices in 10 counties that vary by region, population density, and child care affordability. The report upon which this brief is based describes the landscape of ECE at the local level as it is shaped by federal and state policies, illuminates challenges that counties face in providing access to high-quality programs, and highlights promising practices. This report complements our earlier publication, Understanding California’s Early Care and Education System.

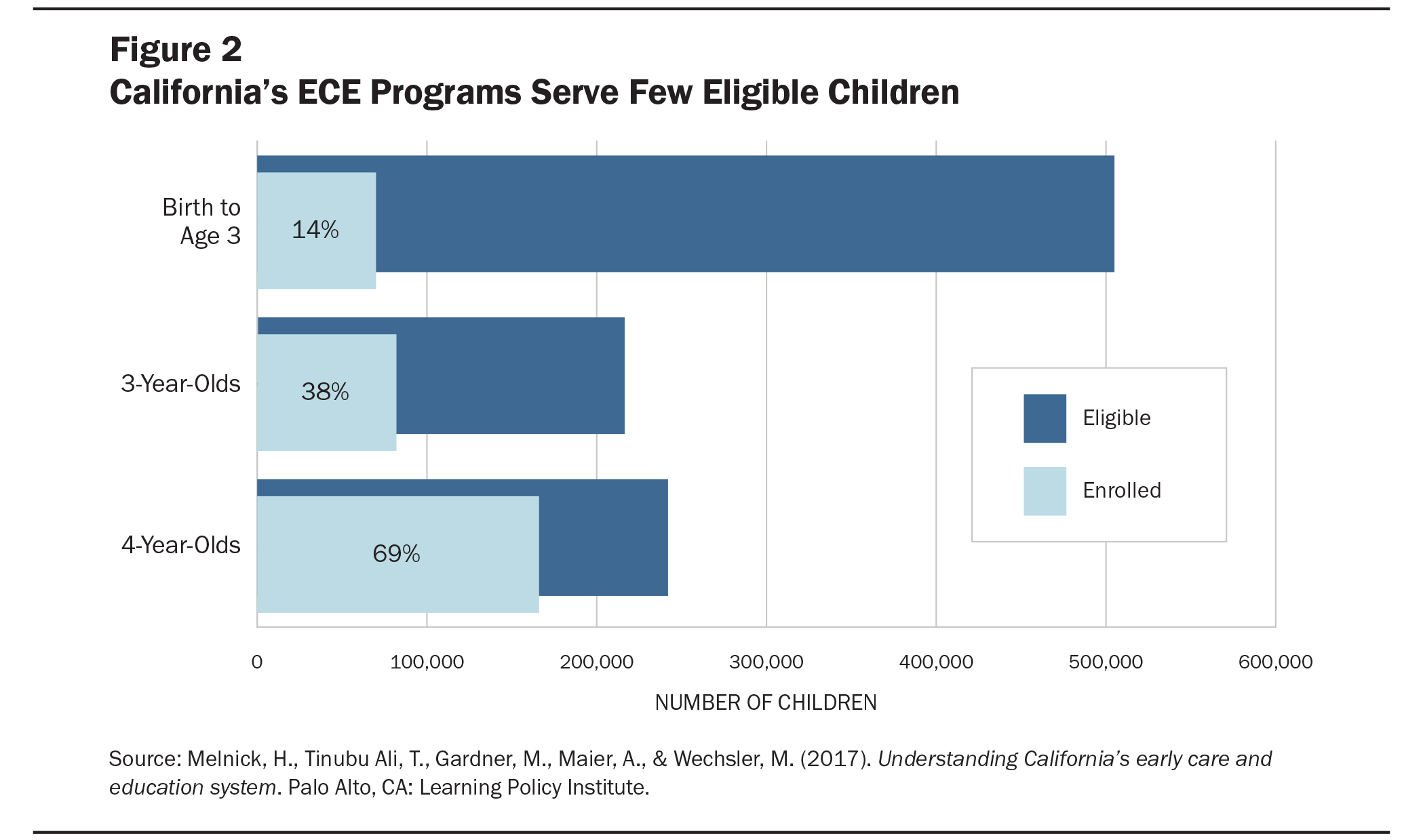

Evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that experiences from birth through the preschool years are critical to children’s development and that high-quality early learning opportunities support children’s school readiness, promote later life success, and yield a return of up to $7 for every $1 invested.Phillips, D. A., Lipsey, M. W., Dodge, K. A., Haskins, R., Bassok, D., Burchinal, M. R., Duncan, G. J., Dynarski, M., Magnuson, K. A., & Weiland, C. (2017). The current state of scientific knowledge on pre-kindergarten effects. Washington, DC: Brookings and Duke Center for Child and Family Policy. Given the long-term benefits of early childhood education (ECE) and the economic returns they generate, California will clearly benefit if all children, from birth to kindergarten, have access to high-quality ECE. Yet, as a state with the sixth-largest economy in the world, California lags behind many states and developed countries in providing ECE. In 2015–16, 1 million California children qualified for subsidized ECE, but just 33% of those eligible were served.Melnick, H., Tinubu Ali, T. Gardner, M., Maier, A., & Wechsler, M. (2017). Understanding California’s early care and education system. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Funding for ECE represents a remarkably small portion of total state spending: Only an estimated 1.8% of California’s budget went to subsidized child care and preschool in the 2017–18 budget. Furthermore, child care and preschool funding was cut drastically during the recession, and the 2017–18 funding level is still $500 million below pre-recession levels.Estimate excludes Head Start and transitional kindergarten. LPI analysis of Schumacher, K. (2017). Child Care and Development Programs in California: Funding Since the Great Recession. Presentation to the ECE coalition, Sacramento, CA; California Department of Finance. (2017). California state budget 2017–18, enacted budget summary charts.

For California to provide all children access to high-quality ECE, state policymakers will need to adopt a comprehensive approach to turn an uncoordinated set of underfunded programs into a true system of supports for children, families, and providers. To build an early learning system that works, the state should take action in four areas.

1. Build a coherent system of ECE administration.

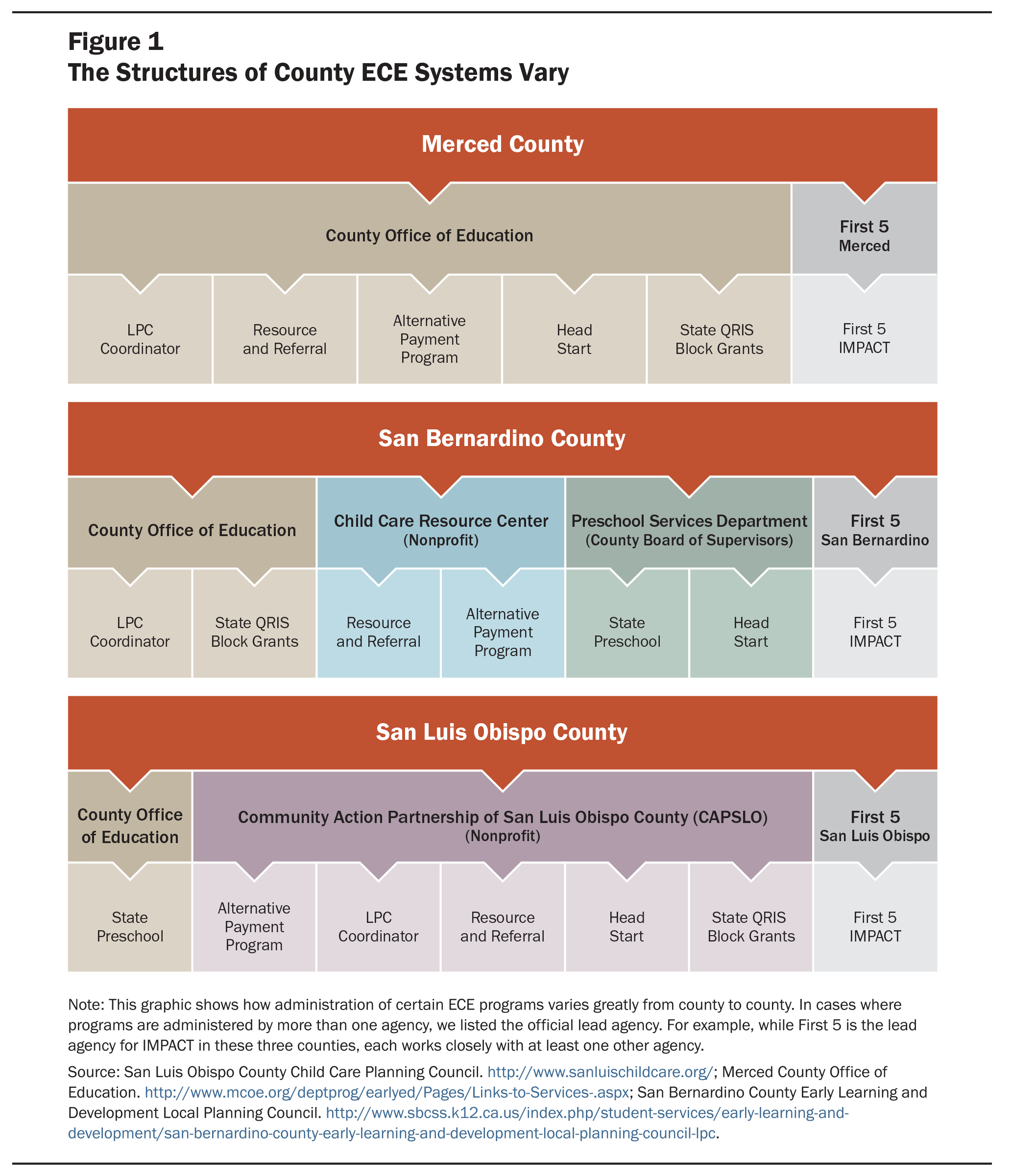

California’s current ECE system is composed of a patchwork of programs with distinct but overlapping purposes and designs. These programs are administered by multiple state agencies, including the California Department of Education, the California Department of Social Services, the California Department of Developmental Services, and First 5 California, and often are funded by and accountable to multiple agencies at the county, state, and federal levels. The complexity at the state level is passed down to county administrators, who do not have the capacity or authority to untangle the web. District-run and special education preschool programs are often isolated.

Navigating this system is daunting for parents and providers. Efforts to link eligible parents to services are often uncoordinated and sometimes fail to match parents to care that meets their needs. There are some bright spots, however. San Mateo and San Luis Obispo counties, for example, coordinate resources and have streamlined processes for families and providers. San Francisco and Sacramento counties maintain centralized waiting lists for ECE programs to efficiently link eligible families with available slots.

Long-term goals

California should take the following steps to ensure its early learning system is cohesive and easy for providers and parents to navigate.

- Identify and invest in a state-level governing body with the authority and expertise to coordinate all ECE programs. The governing body should provide guidance on how to effectively coordinate the state’s various ECE programs with each other and with federal and local ECE initiatives, such as Head Start, transitional kindergarten, and special education preschool. It should also set statewide goals for ECE, develop data and information systems to inform these goals, and build a shared policy agenda. The state could house the governing body for children’s services under a new or existing agency, or it could create a cabinet-level department that works across agencies.

- Fully fund and grant decision-making authority to a single coordinating body at the county or regional level. The local coordinating body should make decisions about local ECE priorities and services, and ensure that school districts, which often operate separately from other ECE agencies, are included in ECE planning so that transitional kindergarten and special education preschool are considered in local decision making. A First 5 Commission, a Local Child Care and Development Planning Council (established by the California Education Code to assess and plan for child care and development services), or a separate overarching agency could play this role.

- Develop a one-stop shop for parents and providers. This one-stop shop would allow families to easily find programs and services that meet their needs and for which they are eligible, and ensure providers are able to fill their available slots to stay in business. Parents and providers should be able to access the one-stop shop through an online portal and through existing brick-and-mortar resource and referral agencies where parents and providers meet with ECE program experts in person. It should offer clear information about ECE programs, their quality, and whether they have space available, as well as a simple form for parents to apply for and renew their eligibility for subsidies.

The online portal also could be used to compile valuable information about programs and children that informs administrators’ and policymakers’ decisions. For example, it could collect information about educator credentials, professional learning activities, and educator wages to inform quality improvement efforts. In building the portal, the state should learn from San Francisco’s success in constructing a comprehensive database, and address the challenges the county has faced, including the misalignment of state reporting requirements for various ECE programs. The state would also need to address the current lack of county capacity for data collection and use.

North Carolina’s public-private partnership, Smart Start, provides a model for a one-stop shop that coordinates and streamlines early childhood services. The initiative began in 1993 and includes 75 nonprofit agencies that assess local needs and direct early childhood investments in the state’s counties. In addition to offering services such as parenting classes, child care program consulting, and case management or referral services for families, Smart Start provides administrative oversight and strategic planning for early childhood programs. In some North Carolina counties, Smart Start coordinates applications and enrollment across programs or agencies to create a single point of entry for families entering the system. For example, in Durham County, the local Smart Start has developed a shared application process that encompasses the state preschool program, Head Start, and Title 1 preschool programs. Families fill out a single application, which they can turn in to any local agency that administers ECE, including the local Department of Social Services, Child Care Services Association, Smart Start, Head Start, and Durham Public Schools. These local partnerships have helped unify what could be a fragmented ECE landscape and developed a more seamless experience for families.Wechsler, M., Kirp, D., Tinubu Ali, T., Gardner, M., Maier, A., Melnick, H., & Shields, P. (2016). The road to high-quality early learning: Lessons from the states. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Immediate steps

California should also streamline ECE administration through a series of more immediate steps.

- Fully fund Local Child Care and Development Planning Councils, which are currently only partially funded and often lack capacity to complete their legislatively mandated needs assessments. Increased funding would allow local planning councils to assess and plan for child care needs.

- Reinstate funding for centralized eligibility lists, which were maintained by local resource and referral agencies from 2007 to 2011 to help link eligible families to providers. Reinstating centralized eligibility lists would make it easier for families to find care that meets their needs and for providers to recruit families. Some counties still run these lists but must cobble together local funds.

- Create a uniform intake process across agencies that streamlines eligibility paperwork. Families should be able to complete one intake rather than submitting paperwork to multiple agencies, making it easier for them to apply for programs, as is being done in San Luis Obispo and San Mateo counties. A uniform intake process would support communication between county agencies about children who qualify for multiple programs—especially children who are homeless, in foster care, or otherwise at high risk—to ensure they receive the services they need.

2. Make ECE affordable for all children birth to age 5.

California has a large unmet need for affordable, high-quality ECE. A mere 33% of children from birth to age 5 who are eligible for publicly subsidized ECE receive it. Care for infants and toddlers is particularly scarce, with subsidies available to just 14% of eligible children. Subsidized care is not always directed to the children who need it most, such as children who are homeless or in foster care. Some counties, however, are making strides to serve a greater portion of 4-year-olds through state or local programs, such as expanded transitional kindergarten in Los Angeles and the Big Lift in San Mateo, which prioritize new preschool programs in areas of highest need.

There are also thousands of children in California whose families earn just over the income eligibility threshold but cannot afford the cost of high-quality ECE. In San Mateo, where housing costs are notoriously high, one administrator described a mother who received a raise which caused her to lose her child care. As she was unable to pay her rent due to increased child care costs, she subsequently became homeless. Recent legislation to raise the eligibility threshold and allow families to keep their care for 12 months helps offset these situations temporarily, but the “income cliff” still exists, and subsidized care for all families remains scarce in every county.

A lack of funding for new slots is a major barrier to access. Paradoxically, however, a large amount of new funding for slots has gone unused, including $101 million in 2014–15. The reasons include low reimbursement rates and the cost of facilities, which keep providers from entering and remaining in the field. Administrative barriers also suppress the supply of care, such as inflexible 1-year contracts that make it difficult for providers to plan financially. Bay Area counties have worked to mitigate these problems through a pilot program that raises reimbursement rates, helps providers manage their contracts, and increases the income eligibility threshold for participating families.

Even when subsidies are available, many parents need full-day or alternative-hour care that can be difficult to find. Rural areas have few programs, and those that exist may be far from where families live or work.

Long-term goals

California should take the following steps to making ECE affordable for all children under the age of 5.

- Establish universal preschool for 4-year-olds. Through transitional kindergarten, the state has begun to expand the availability of ECE to 4-year-olds, regardless of family income. It should continue down this path to universal pre-k, as has been done by Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Washington, DC. As in other states, this universal preschool program could include a mix of public and private providers, as long as all providers meet quality standards set by the state. Incorporating existing private preschools into the system would preserve choices for parents and ensure the stability of current providers, many of which also serve infants and toddlers. Full-day programs should be available for children whose families work. California’s universal preschool program could also offer wraparound services, such as health screenings and family engagement services, to children from low-income families and children with special needs.

- Make preschool affordable for all 3-year-olds using a sliding fee scale. Pre-k programs could be made available to 3-year-olds on a sliding fee scale based on a family’s ability to pay for care, with full subsidies for the lowest income families. All of California’s full-day ECE programs, except transitional kindergarten and Head Start, currently use a version of a sliding scale that requires families to pay fees of up to 10% of family income. However, these programs also have an “income cliff,” meaning that once families earn even a dollar over the maximum income level, they lose their benefits entirely.

Over time, California should eliminate the income cliff by using a sliding fee model in which families pay progressively more for care as their incomes increase. This model would prevent parents who receive a small raise from losing their child care benefits or their opportunity to work. It would also increase socioeconomic integration in California’s ECE programs, which has been linked to better child outcomes.Reid, J. L., & Ready, D. D. (2013). High-quality preschool: The socioeconomic composition of preschool classrooms and children’s learning. Early Education & Development, 24(8), 1082–1111; Schechter, C., & Bye, B. (2007). Preliminary evidence for the impact of mixed-income preschools on low-income children’s language growth. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(1), 137–146; Reid, J. L., & Kagan, S. L. (2015). A better start: Why classroom diversity matters in early education. Washington, DC: Poverty & Race Research Action Council. Finally, a sliding fee scale has the benefit of requiring a smaller state investment than universal preschool by capitalizing on both public dollars and private contributions from higher income families. Funding that currently goes to state preschool and child care vouchers for 3- and 4-year-olds could be leveraged to subsidize lower income families.

- Ensure access to subsidized child care on a sliding fee scale for all infants and toddlers. Working parents should have access to high-quality child care, also on a sliding fee scale, that provides significant subsidies for families with low incomes and requires greater contributions from families with higher incomes. This child care should include enough full-day care to meet parents’ needs, with some providers offering night and weekend care.

To meet the demand for care, there are two programs the state could expand: the Alternative Payment vouchers that families can use on the private market, and state-contracted child care centers and family child care homes. The voucher system allows families to find care that matches their needs and preferences, and is the program that can be most readily expanded without major investments in infrastructure. State-contracted centers and family home care providers are held to higher quality standards, but they do not currently have capacity to serve more infants and toddlers. To support either option, the state would need to address the insufficient supply of licensed providers by providing adequate reimbursements and supporting their operations. The state has begun this process in recent years with modest increases in the reimbursement rates paid by the state to subsidized providers, but it needs to go further.

Immediate steps

California should expand access to ECE and ensure an adequate supply of licensed providers through a series of more immediate steps.

- Expand the availability of full-day programs to better meet the needs of working families. Allowing state preschool programs, especially those that utilize school facilities, to operate for a full day on a school-year calendar is one way to increase the availability of full-day slots.

- Provide funding for facilities to providers who are willing to serve more infants and toddlers. Funding could be used to convert facilities built for older children or expand the capacity of family child care homes.

- Increase funding for the Revolving Loan Fund, a current program run by the California Department of Education to support ECE contractors’ efforts to purchase and/or renovate facilities. To make the loans useful to providers, the state should provide technical assistance and relax overly severe restrictions on the type of buildings and renovations allowed. Assisting providers with facilities likely will reduce the amount of funding returned to the state, given that difficulty acquiring facilities is one of the barriers to expanding subsidized care.

- Change 1-year state contracts for state pre-k and child care to 5-year grants, as is the case with Head Start. Five-year grants would allow providers to plan more effectively for the future and to reduce unspent funds currently being returned to the state. Additionally, the state could allow counties to reallocate unspent funds within the county when programs under-earn or over-earn their contracts, as several Bay Area counties have done under the child care subsidy pilot.

- Increase reimbursement rates for infant and toddler programs. Reimbursement rates for infant and toddler care are woefully inadequate to support the cost of maintaining sufficient staff-to-child ratios and providing high-quality care. Raising infant and toddler reimbursement rates could help address the state’s severe shortage of care for this age group. The state only offers state-contracted centers 1.4 times the preschool rate to serve toddlers and 1.7 times to serve infants, despite requiring more than twice as many staff to care for these younger children.Reimbursement fact sheet Fiscal Year 2015–16, 2015, California Department of Education (accessed 3/31/17). A rate for infant and toddler programs that is at least double the preschool rate would better reflect the differences in staffing needs across infant, toddler, and preschool settings.

3. Build a well-qualified workforce.

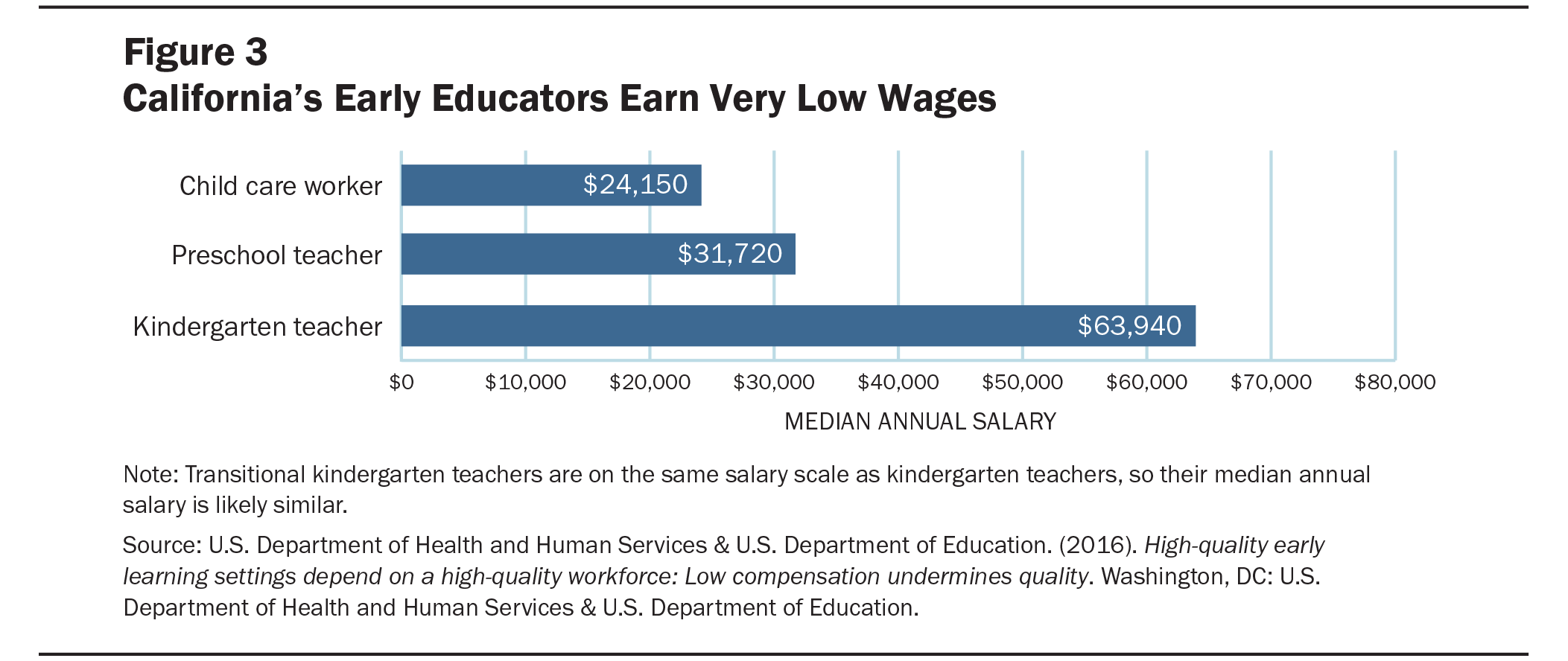

Specialized preparation for ECE educators focused on child development and early childhood learning is associated with stronger outcomes for children.Bueno, M., Darling-Hammond, L., & Gonzales, D. (2010). A matter of degrees: Preparing teachers for the pre-k classroom. Washington, DC: The Pew Center on the States. More than 107,000 professionals provide ECE in California, but inconsistent state requirements lead to disparate qualifications among these educators, even for children of similar age and need. However, ECE programs across California struggle to recruit and retain qualified educators, even when requirements are low. High turnover, driven by low wages and challenging working conditions, creates instability that negatively affects children. Wages are so low that half of the child care workforce receives public assistance.Whitebook, M., McLean, C., & Austin, L. J. E. (2016). Early childhood workforce index 2016. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. To boost salaries, some school districts, such as Sacramento’s Elk Grove Unified, combine funding from multiple sources to create full-day positions with a living wage.

ECE programs across the nation have increased educator qualification requirements in recent years, but California’s credentialing requirements for ECE educators have lagged behind. Many early childhood educators struggle to attain a higher degree; tuition is a barrier, as is completing relevant coursework due to a lack of alignment and articulation across institutions of higher education. To encourage aspiring and current educators to complete their coursework, San Mateo’s community colleges support full-time staff who specialize in advising ECE students. A cross-sector collaborative in Los Angeles County has made sure college courses are comparable and credits are transferable across colleges in the region.

Long-term goals

California should take the following steps to build a well-qualified workforce.

- Increase expectations and support for educators’ higher education and training, starting with preschool. California should ensure that children of similar age and need in state-subsidized programs have access to educators with comparable education. Research has found that pre-k programs with the strongest sustained impact on child outcomes—including transitional kindergarten—require educators to have a bachelor’s degree and specialized training in ECE.Bueno, M., Darling-Hammond, L., & Gonzales, D. (2010). A matter of degrees: Preparing teachers for the pre-k classroom. Washington, DC: The Pew Center on the States; Manship, K., Quick, H., Holod, A., Mills, N., Ogut, B., Chernoff, J. J., Anthony, J., Hauser, A., Keuter, S., Blum, J., & González, R. (2015). Impact of California’s transitional kindergarten program, 2013–14. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research; Meloy, B., Gardner, M., Wechsler, M., & Kirp, D. (2017). What Can We Learn From State-of-the-Art Early Childhood Education Programs? Unpublished manuscript. Currently, California’s preschool programs have varying, often low, expectations for staff teaching the same age group. Transitional kindergarten, for example, requires a B.A. and a teaching credential, while there is no degree requirement for California’s state preschool program or private preschool programs receiving vouchers.

ECE permits for various roles are based on the number of credits individuals have secured, without a framework for the content of those credits. The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing has proposed changes in ECE teacher licensing requirements to strengthen the knowledge base of educators based on research about what teacher competencies are associated with strong student learning outcomes, though these changes have not been enacted.California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, Child Development Permit Advisory Panel. Increased requirements for educators should be paired with support in attaining a higher degree, and should be phased in over time in order to retain the current workforce and ensure an adequate supply of educators.

Following the creation of its state pre-k program in 1999–2000, New Jersey gave pre-k teachers, many of whom held only an associate-level degree, until late 2004 to earn their bachelor’s degree and credential. The state accompanied this new requirement with scholarships of up to $5,000 per year for tuition as well as supplemental support for books and materials.Whitebook, M., Ryan, S., Kipnis, F., & Sakai, L. (2008). Partnering for preschool: A study of center directors in New Jersey’s mixed-delivery Abbott program. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley; Ryan, S., & Lobman, C. (2006). Carrots and sticks: New Jersey’s effort to create a qualified pk-3 workforce. New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development. During this period, an expanded pool of substitute teachers was also available so that teachers could attend school. New Jersey concurrently expanded the capacity of higher education to train early childhood educators by developing a specialized preschool to 3rd-grade certification with multiple pathways to licensure and by supporting the development of transfer agreements between 2- and 4-year schools. Universities were supported to offer training through online and on-site courses and clinical support. In 2000, only 15% of early childhood teachers in private settings met the state’s criteria. By 2004, approximately 90% of the participating districts’ early childhood teaching force had a bachelor’s degree and were at least provisionally certified. By 2007, 97% were fully certified and had completed college.MacInnes, G. (2009). In plain sight: Simple, difficult lessons from New Jersey’s expensive effort to close the achievement gap. New York, NY: The Century Foundation; Bueno, M., Darling-Hammond, L., & Gonzales, D. (2010). A matter of degrees: Preparing teachers for the pre-k classroom. Washington, DC: The Pew Center on the States.

- Continue to raise reimbursement rates to enhance educator wages. As the state raises qualifications for ECE educators, it should make investments that can support higher wages so that providers can recruit and retain educators with the specialized knowledge and skills they need to teach young children. One avenue for supporting higher wages is increasing program reimbursement rates for all publicly subsidized providers, which the 2016 and 2017 budgets begin to do. For preschool, the state should aim to raise rates to the level of per-pupil funding spent on transitional kindergarten, which supports educators with a bachelor’s degree, a teaching credential, and coursework in ECE. Rates should similarly increase to support a living wage for educators of younger children, especially given that they are required to have specialized knowledge in child development and age-appropriate instruction.

The state should also reform its reimbursement rate structure to ensure that programs requiring higher staff credentials are able to pay higher wages. The state’s current system utilizes two different rates: the Standard Reimbursement Rate and the Regional Market Rate. As a result, state-contracted centers in high-cost counties are reimbursed as much as 50% less than their counterparts on the private market, despite the fact that educators in state-contracted centers are held to higher qualification standards.LPI analysis of the following sources: Management Bulletin 16–11, 2016–17, California Department of Education; Education Code Section 8265.5; CalWORKs Child Care Programs RMR Ceilings, August 2016, California Department of Social Services. This means that educators with stronger credentials in state centers may receive lower wages than their less-educated peers on the private market. Unifying state reimbursement rates and staff qualifications expectations into a single system would help to improve staffing quality and create more equitable wage structures across the public and private sectors.

Immediate steps

California should also help ECE educators increase their training and compensation through a series of more immediate steps.

- Increase the availability of full-day slots in state-funded programs to enable more educators to work full time and earn a living wage. Because there are too few full-day programs, many ECE educators must work part time, which further undermines their ability to earn an adequate salary. The state could facilitate more full-day slots by offering technical assistance to providers for combining funds from multiple part-day programs to create full-day programs.

- Offer paid hours for professional learning time to state-contracted centers so that educators can collaborate with colleagues and are not forced to attend trainings, unpaid, on nights and weekends. The state could support professional learning through higher reimbursement rates or grants. The state might also incentivize school districts to include ECE staff in professional learning with early elementary teachers. Fillmore Unified in Ventura County, for example, has developed a summer institute in which state preschool, transitional kindergarten, and kindergarten educators all co-teach summer classes, facilitating preschool-to-kindergarten transitions and allowing these teachers to learn from one another.

- Support alignment and articulation among higher education programs across the community college and university systems. In Los Angeles, Partnerships for Education, Articulation, and Coordination through Higher Education—PEACH—provides a model for improving articulation and alignment among colleges to make sure courses are comparable and credits are transferable across schools and institutions.

- Expand funding for the Child Development Staff Retention Program (AB 212). AB 212 allows counties to provide higher education scholarships to improve the training of ECE educators, but it is currently underfunded at only $11 million annually. Expanding AB 212 would boost the number of educators pursuing an advanced degree.

- Implement a Teacher Education and Compensation Helps (T.E.A.C.H.) program, which provides scholarships to help ECE professionals pursue associate, bachelor’s, or master’s degrees in early childhood education and supports improvements to higher education, such as articulation agreements, to ensure coursework for an associate degree also counts toward a bachelor’s degree. T.E.A.C.H. was developed in North Carolina in 1990, and states can license the program, which gives them access to unlimited technical assistance and requires they follow the research-based model. Currently, 26 other states have implemented a T.E.A.C.H. program, which often includes a small bonus or raise at the completion of a degree.Teach Early Childhood National Center. (n.d.). Organizations that house T.E.A.C.H.

- Invest in higher education advising programs for current or aspiring ECE educators. Advising programs should have specialized ECE advisers who help students choose coursework that culminates in a degree, as San Mateo’s community college district has done.

4. Improve the quality of all ECE programs.

California’s ECE programs vary greatly in their quality standards, meaning that similar children may receive very different opportunities within the state’s subsidized system. Recent state investments to monitor and enhance quality focus primarily on quality rating and improvement systems (QRISs). Unlike most other states, which have a statewide QRIS, California’s counties administer QRIS locally, with the support of regional and state consortia. They do, however, use a common statewide framework that measures many aspects of quality, including the quality of adult-child interactions through the research-based Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), which has been linked to improved child outcomes.

County QRISs vary in which providers participate, which incentives are provided, and what types of supports are available to help providers improve. Participation in QRIS is voluntary, and overall only 14% of providers participate,In 2016, only 5,956 of the more than 44,000 licensed care providers in the state participated in QRIS. Unpublished data from First 5 California (personal communication, November 20, 2017); Resource and Referral Network. (2015). California: Family and child data. San Francisco, CA: Author. leaving most providers with little support. Counties must choose between in-depth quality improvement activities for a few providers or less intensive supports for more providers. Most counties focus on coaching in their efforts to support providers. For example, Child360, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit, has employed a comprehensive data-driven coaching model for many years. It is important that the QRIS framework—as California’s primary mechanism for improving quality—continue to be improved to ensure its effectiveness, especially as its use expands to more providers. Yet, research on how to improve the QRIS process is scarce: The only large-scale study of California’s QRIS was conducted during its first years of development.

Categorical grants, such as the California State Preschool QRIS Block Grant (which is available only to preschool classrooms in state-contracted centers) and the Infant and Toddler QRIS Block Grant (which narrowly supports the participation of infant and toddler ECE providers in QRIS activities), have complicated county and regional efforts to support all providers equitably. Further, unstable and uncoordinated state funding makes it difficult for counties to plan for the future and to provide consistent support for providers. In Northern California, seven counties have pooled resources to develop a more comprehensive QRIS and offer stronger incentives and training than any county could offer on its own. Contra Costa County broadens the reach of its coaching program by supporting it with federal funds.

Long-term goals

California should take the following steps to build a system of high-quality early learning.

- Raise quality requirements for programs with the lowest standards. Programs receiving state funds currently vary greatly in their requirements for educators, staff-to-child ratios, and educational standards. Quality requirements for private programs receiving state-funded vouchers are particularly low compared to the state’s other ECE programs. The state should ensure that all of its investments go toward high-quality programs. For example, preschool programs should require lead teachers to have a bachelor’s degree and ECE-specific coursework. Programs for younger children should require educators to have the specialized knowledge and training they need to work effectively with young children. All programs should be expected to have an age-appropriate curriculum or educational plan. Recognizing that the state currently offers subsidies to many private providers, it should phase in increased requirements over time and take steps to help programs improve.

The Early Head Start-Child Care Partnerships (EHS-CCP) initiative provides an example of how to invest in private providers to raise the quality of child care programs at scale. The EHS-CCP program blends funding from two federal sources, Early Head Start and the Child Care Development Fund, to support higher quality care in private settings. Investments go toward improving staff-to-child ratios and reducing class sizes, supporting educators’ skills through ongoing job-embedded professional learning, and enabling effective family engagement. Quality enhancements are offered to child care centers and family child care providers that meet the needs of working families by offering flexible and convenient full-day and full-year services. Because EHS-CCP is in its early stages, the extent of the program’s impact is not yet known. However, national studies of the program report early successes with regard to the number of providers receiving support such as coaching and the number of infants and toddlers receiving comprehensive services.Office of Early Childhood Development, Administration for Children and Families. (2016). Early Head Start-Child Care Partnerships: Growing the supply of early learning opportunities for more infants and toddlers. Year one report, January 2015–January 2016. Washington, DC: Author.

- Ensure all state-supported programs participate in quality-improvement activities. Currently, a very small portion of providers participate in QRIS, and counties have been left to their own devices to choose who participates and how. The state should play a greater role in ensuring equity of access to quality-improvement activities among providers and the children they serve. California should continue investments in QRIS with the goal of universal participation, eventually requiring the participation of all providers receiving state funds. To support county QRISs in achieving this goal, the state could increase investments in the state QRIS hub, Quality Counts California, which provides technical assistance and promotes cross-county exchanges of expertise.

North Carolina, which first started its QRIS in 1998, has a statewide system that requires participation in its QRIS for all licensed programs, including state preschool and Head Start. State-subsidized programs must meet a minimum QRIS rating; for instance, state pre-k programs are required to maintain three out of five stars. Further, the QRIS allows the state to reimburse higher quality centers at a higher rate. A five-star child care center in Mecklenburg County, for example, receives a 63% higher reimbursement rate than a provider offering one-star care in the same community.Wechsler, M., Kirp, D., Tinubu Ali, T., Gardner, M., Maier, A., Melnick, H., & Shields, P. (2016). The road to high-quality early learning: Lessons from the states. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Child Care and Early Education (2016). Subsidized child care market rates for child care centers. Raleigh, NC: Author. This higher rate helps to offset the cost of paying better educated teachers or purchasing additional classroom materials and incentivizes quality improvement. North Carolina has also supported extensive parent outreach and education to publicize ratings and inform families about the features of quality. Recent research indicates that the QRIS has been effective at boosting the quality of care across the state.Bassok, D., Dee, T., & Latham, S. (2017). The effects of accountability incentives in early childhood education. NBER Working Paper No. 23859. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Ensure access to coaching and other job-embedded supports for all ECE providers. The state should provide all educators with the opportunity to participate in activities that research has linked to effective educator development, especially coaching and staff collaboration time.Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Coaching is not funded or required for California’s ECE programs except Head Start, although many California counties are already investing in coaching for educators through QRIS. The state could begin to expand access to coaching by making greater investments in this aspect of QRIS and supporting training for ECE coaches at the state or regional level. For programs with state contracts, such as state preschool and state-contracted centers, the state could require and fund coaching for all providers.

Immediate steps

California should also improve program quality in the short term, through a series of more immediate steps.

- Ensure state quality improvement funds are available to all providers by increasing the flexibility of their use, particularly for categorical grants such as the California State Preschool QRIS Block Grant, which is available only for state preschool providers. This would be consistent with First 5’s IMPACT grant, which fosters the participation of all types of providers in QRIS. Making this change will mean that QRIS funding is not tied to a limited subset of providers.

- Centralize and support training for QRIS assessors. Counties currently train and deploy their own staff to rate programs on the QRIS matrix. Having centralized training could increase rating consistency and free up county-level staff to focus on supporting local providers.

- Invest in research to continuously improve the effectiveness of the QRIS, especially as more providers and program types participate, so that the QRIS framework, which sets standards of quality and is shared across all counties, accurately identifies high-quality environments and teaching practices across all ECE programs, supports program improvement, and provides parents with useful information about quality.

Conclusion

High-quality ECE can put children on the path to success in school and in life. But many California children do not have access to ECE, and not all ECE programs in California are of high quality. The patchwork of underfunded programs and services available to young children and their families is incoherent and insufficient. California should reconsider its approach to meeting the needs of children and families so that each piece of the system is of high quality and together they create a coherent system. Model practices exist in many of California’s counties and in other states. It is time for the state to build on these successes. Increasing access and improving quality will require both budgetary and operational attention but ultimately can create a system that, as a whole, will serve California’s children better.

Building an Early Learning System that Works: Next Steps for California (policy brief) by Hanna Melnick, Beth Meloy, Madelyn Gardner, Marjorie Wechsler, and Anna Maier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by grants from the Heising-Simons Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.

Photo by Drew Bird.