District Leadership for Racial Equity: Lessons From School Systems That Are Closing the Gap

Summary

This research brief presents cross-case findings from a study of leaders advancing racial equity in four school districts in the southern United States: Edgecombe County Public Schools in North Carolina, Hoke County Schools in North Carolina, Jefferson County Public Schools in Kentucky, and Pflugerville Independent School District in Texas. We investigate the policies and practices district leaders implemented to reduce persistent disparities in opportunities and outcomes for students of color, including improved test scores, higher graduation rates, and lower rates of exclusionary discipline. These leaders all pursued five key racial equity district leadership strategies: (1) creating a strategic plan for equity; (2) building adult capacity, commitment, and accountability; (3) using data to drive progress toward racial equity; (4) acquiring and allocating resources equitably; and (5) sustaining leadership efforts over time. This brief is based on the book District Leadership for Racial Equity: Lessons From School Systems That Are Closing the Gap.

The Role of District Leaders in Addressing Racial Inequities

Despite decades of public education reforms, race and class remain among the most reliable predictors of student success in schools across the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic both highlighted and deepened educational inequities. Simultaneously, a nationwide racial reckoning emphasized that this reality is no accident; it is the consequence of school systems that were designed to exclude Black, Indigenous, and other students of color and that continue, in many cases, to underserve students of color and low-income students. It is evident that more attention and resources are needed to support sustained change that can eradicate opportunity and achievement gaps, particularly in the South, where the districts featured in this brief are located.

In this region, Black and Hispanic people are even more acutely overrepresented among those living in poverty, students from low-income families are consistently underprepared for standardized assessments of student progress, Black and Hispanic students perform well below the median on national assessments of 4th- and 8th-grade reading and math skills, and Black students face exclusionary discipline at higher rates compared to their Hispanic and White peers. These gaps are driven by persistent racial inequities in educational resources and opportunities in most states, which reflect the anti-literacy laws and segregationist policies of the 19th and 20th centuries. At the same time, the South is home to large and resilient communities of color, an epicenter for racial equity activism, and the site of enduring legacies of what is possible when racial injustice is named, faced, and fought.

Effective district leaders are pivotal in achieving significant shifts that address racial inequities within school systems. The cases in this study seek to deepen the field’s knowledge of equity-oriented leadership and strengthen the capacity of district leaders to advance racial equity in their school systems. Racial equity leadership refers to the leadership skills that district leaders use to create the conditions for all children to succeed academically; develop social-emotional skills; and be prepared for work, life, and civic participation.

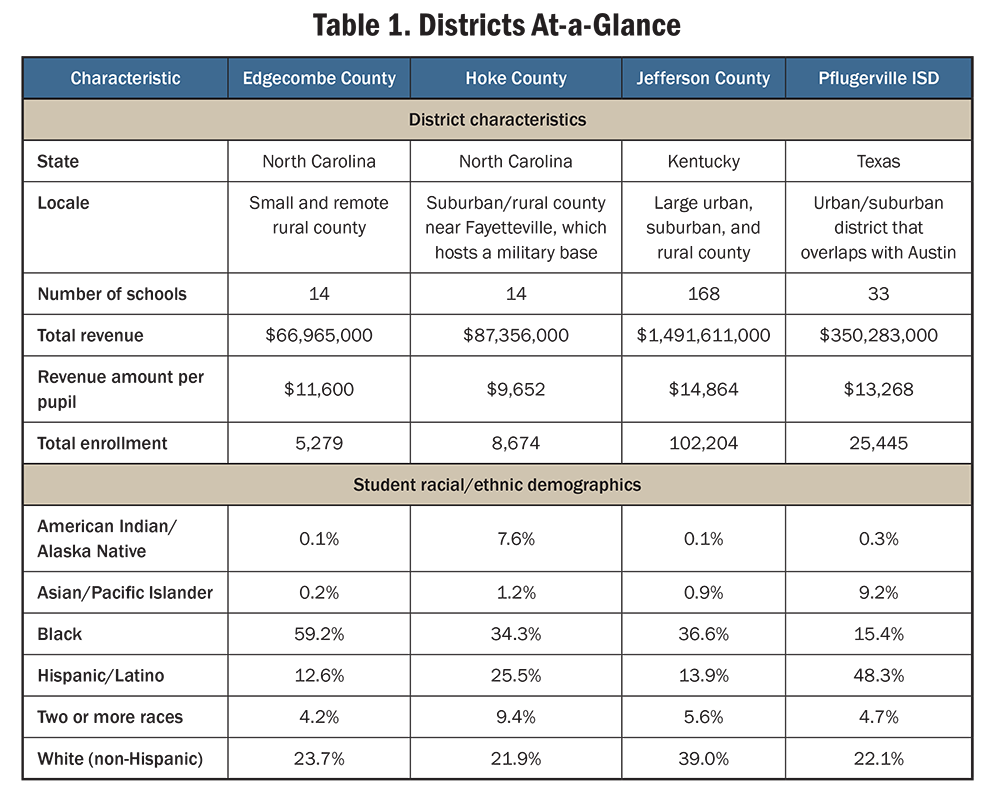

We studied leadership for racial equity in Edgecombe County Public Schools and Hoke County Schools, both in North Carolina; Jefferson County Public Schools, Kentucky; and Pflugerville Independent School District, Texas. These school districts vary in size, student demographics, and context (see Table 1). Yet there are many similarities in how leaders were able to make racial equity advances across these distinctive contexts.

Edgecombe County Public Schools (Edgecombe) is a sparsely populated rural district in northeastern North Carolina that serves a predominantly Black student body. It includes the town of Princeville, the first town in the United States founded by formerly enslaved freed people after the end of the Civil War. The town was founded on the only land available to Black residents at the time, a swampy area on the Tar River that has been a frequent site of devastating flooding since at least the 1800s. As the legacy of environmental racism continues to reverberate in the district, the county is one of the neediest in the state in terms of health, education, and economic development. When Dr. Valerie Bridges was promoted in 2017 from assistant superintendent to superintendent of Edgecombe, it had been identified as a low-performing district by the state. Under the high stakes of state scrutiny, Bridges corrected resource disparities and launched initiatives that have retained and retrained staff, while improving opportunities and outcomes for students through a strategy of acceleration rather than remediation. She introduced innovations like project-based learning, a Spanish immersion program, and Early College High School in the highest-need areas of the county. Within 2 years, the district saw stunning progress: Reading and math test scores accelerated at twice the state rate of growth, suspensions were sharply reduced, and graduation rates climbed. By 2022–23, Edgecombe exited its low-performing district status and began to attract creative educators as a hub for innovation.

Hoke County Public Schools (Hoke) is also a largely rural county in North Carolina serving predominantly students of color (American Indian, Black, and Hispanic) and was a candidate for state takeover when Dr. Freddie Williamson became the county’s first Black superintendent in 2006. According to an ongoing school finance lawsuit in which Hoke County was a plaintiff, generations of students had been deprived of their right to a “sound basic education.” By 2020, when Williamson passed the mantel of leadership to his associate superintendent, graduation rates had climbed to reach the state average, and academic achievement had sharply improved, reaching or nearing state averages for a more advantaged population of students, with the steepest gains for American Indian and Black students. New programs and partnerships aimed to create a “world-class learning center” by expanding early learning, focusing on 21st-century learning and teaching strategies, and expanding Advanced Placement courses and career and college-going pathways, with a shared commitment to meet the needs of each child.

Jefferson County Public Schools (Jefferson County) is a large school district encompassing Louisville, Kentucky, and the surrounding county. Jefferson County serves a demographically diverse population of predominantly Black, Hispanic, and White students. Building on a legacy of reform beginning with desegregation in the 1970s, Jefferson County has struggled toward racial equity with resilience and tenacity. A 2017 state audit found widespread racial disparities that demanded a corrective action plan, putting the district at risk of a state takeover. Superintendent Dr. Donna Hargens accelerated the district’s efforts to put an impactful racial equity plan into effect and established an enduring infrastructure to advance that vision: The Diversity, Equity, and Poverty Division has steadily used data analyses and community engagement to expand academic opportunities focused on deeper learning and transformative school models throughout the district. The district increased access to advanced academics, reduced exclusionary discipline, and improved its rates of postsecondary readiness for every group, nearly doubling the rates for Black graduates. Under the leadership of Hargen’s successor, Dr. Marty Pollio, Jefferson County was released from the state’s corrective action plan in 2020.

Pflugerville Independent School District (Pflugerville) is a rapidly growing suburban district fueled by development and migration from neighboring Austin, Texas. As Austin residents from the predominantly Black and Hispanic community of East Austin relocated to the city of Pflugerville, the district transitioned from serving majority-White students to majority students of color. With continuous support from the board of trustees and central office staff, leaders in Pflugerville have rallied the community behind a sense of pride in cultural diversity. In 2017, Superintendent Dr. Douglas Killian systematized the district’s equity orientation by establishing its first-ever strategic plan, bringing a cohesive approach to change management and allocating resources deliberately to enact its goals. He leveraged a shared commitment to “passionately serve the best interests of students” to drive educational reforms. Three years into the strategic plan, the district saw improvements in educational outcomes, decreased suspensions, and increased rates of students graduating college- and career-ready, with the largest improvements among Black, Hispanic, and emergent bilingual students.

Despite contextual differences, there were similarities in how superintendents strategically led their staff members and community through this work. In each case, district leadership strategies to advance racial equity included: (1) creating a strategic plan for equity; (2) building adult capacity, commitment, and accountability; (3) using data to drive progress toward racial equity; (4) acquiring and allocating resources equitably; and (5) sustaining leadership efforts over time.

Creating a Strategic Plan for Equity

Leaders often entered fragmented systems facing serious challenges, including dissentious communities and the threat of state takeover. In each case, they built consensus and cohesion by creating strategic plans with their boards and communities that identified needs and pursued equity through specific steps to achieve shared goals. Their collaborative development and concrete goals ensured that district teams could leverage strategic plans as living documents to drive change, rather than static reports that sit on a shelf. They engaged community members to identify and address racial inequities, set aspirational visions of educational opportunity, and identified and pursued action plans with data-based evaluations of progress.

Engage Community Members to Identify and Address Inequities

Leaders fostered community input and cultivated support for equity aims outside of schools and district buildings. For example, leaders in Edgecombe established a Blue Ribbon Commission on Educational Equity to reciprocally engage hundreds of stakeholders, including students, family members, business leaders, elected officials, nonprofit partners, and district staff members through community forums. Leaders were inclusive yet strategic in their engagement: Rather than waiting to get everyone on board, they built a critical mass of key supporters that harnessed the power of students and families, political leaders, and local industry.

Through meaningful dialogue, leaders developed politically palatable messaging that directly addressed equity concerns in the community, which necessarily took different forms. For example, leaders in Jefferson County created a District Commitment to Racial Equity policy, while leaders in Pflugerville developed a core value positioning the district’s cultural diversity as a strength. In both Hoke and Edgecombe, leaders described equity aims in terms of interrupting cycles of poverty. Through clear and consistent messaging, leaders pushed forward with equity champions while strategically cultivating greater capacity, commitment, and accountability across the adults within their systems.

Set an Aspirational Vision of Educational Opportunity

Leaders engaged their communities in future-facing discussions to develop aspirational visions of educational outcomes. Jefferson County established the vision that all students “graduate prepared, empowered, and inspired to reach their full potential and contribute as thoughtful, responsible citizens of our diverse world.” Edgecombe developed aims for all district graduates to live out their purpose and passion, possess global awareness and agency, contribute positively to their community, and demonstrate resilience in the face of challenges. These visions define student success holistically, going beyond academic achievement to positive self-identity, economic and political agency, and postsecondary success.

District visions also included commitments to removing social factors as predictors of student success. For example, through one of its core values, “Diversity is our strength,” leaders in Pflugerville positioned cultural identities as learning assets—not liabilities. Shared messaging, planning, and policies embraced by the community and school board provided political cover for challenges and pushback that teams encountered during implementation.

Identify and Pursue Action Plans

Leaders operationalized broad visions into concrete priorities, goals, and actions. All districts in this study established priorities that spanned organizational departments and teams, including curriculum and instruction, school culture and climate, talent recruitment and retention, and finance and operations. Hoke Superintendent Williamson described the importance of distributed leadership for implementing systemwide reform: “Let the talented people you have do the work. Education is too large, too dynamic, and too complex for one person to make all the decisions.”

For this reason, leaders in all four districts emphasized that advancing equity was everyone’s work. Jefferson County leaders hired a cabinet-level chief equity officer to lead the district’s Diversity, Equity, and Poverty Division in close coordination with other divisions and school leaders. Pflugerville leaders created cross-functional action teams for each strategic priority. Staff reported that the district’s equity aims were highly visible and imbued in every message. Former Executive Director of Special Programs Cara Schwartz explained the importance of leadership at every level of the organization:

Superintendent leadership matters, principal leadership matters, and the relationship between your superintendent and your board members matters. That has been the breath of fresh air coming here. The superintendent sets the scene, and we can do the work that we do because we have a very supportive board of trustees. All of those pieces have a great influence, I believe, on that impact that we’re able to help with our campuses and our students.

Build Adult Capacity, Commitment, and Accountability

Leaders established racial equity as everyone’s work through organizational cultures that (1) recognized the assets learners bring to their education and (2) held adults—not students—responsible for addressing inequities that resided in the system. They established core leadership teams invested in advancing equity, developed staffwide equity mindsets, and expanded ambitious instruction and whole child supports.

Establish a Core Leadership Team Invested in Advancing Equity

In all cases, superintendents advanced equity reforms with leaders across multiracial, multifunctional teams. Pflugerville Superintendent Killian described the benefit of building collective efficacy: “You can get some things done as a superintendent just by force of will, but it sure does work a lot better if you’re going with a group.”

Staffing decisions were central in developing an effective team. All of the districts sought to recruit innovative leaders interested in disrupting persistent inequities—both at the superintendent level and in other central office and site leadership roles. Superintendents promoted principals and teacher leaders with proven track records and counseled out leaders who were not aligned with the equity vision. Some carried out major staffing changes at the start of their terms, for example, hiring the chief equity officer in Jefferson County, replacing campus principals in Hoke, and changing the organizational structure in Pflugerville. Superintendents also refined their leadership teams over time. Edgecombe developed a multi-tiered staffing model, enabling teachers to advance into leadership positions for greater instructional impact, and Grow Your Own teacher programs were launched in Edgecombe and Pflugerville.

Develop Staffwide Equity Mindsets

Leaders worked to cement new asset-based narratives about learners in their districts. They leveraged professional learning to cultivate equity mindsets in all staff, from instructional coaches, to teachers, to school registrars. Staff trainings established shared concepts and language, such as the difference between equity and equality, the effects of adverse childhood experiences, and the impacts of unconscious bias. Importantly, this mindset work accompanied and facilitated the implementation of new instructional expectations, which applied to all staff without exception, and the use of tools like equity walk-throughs. Professional learning communities and coaching built on these understandings.

District leaders noted that action can and must coincide with mindset change, which can be slow and difficult to measure. Jefferson County Superintendent Pollio explained:

We don’t have everybody on board. When you have 17,000 employees, you’re not going to. … But what you have to do, I believe, is just be consistent and courageous, and make the case and continue to make the case. More than anything, it is making sure not just to do lip service to it or [do] the relatively easy things. It’s the courage and the ability to just continue to play that long game, to keep pushing hard.

Expand Learning for Ambitious Instruction and Whole Child Supports

As they developed equity mindsets, leaders simultaneously increased educators’ knowledge base of how students learn and develop. They created professional learning related to ambitious instruction and whole child supports, which transformed student learning experiences from basic or remedial education to deeper learning, including project-based learning, language immersion, accelerated learning, and social and emotional learning as foundations for academic success. Districts shifted from punitive punishments toward inclusive instruction and positive behavioral supports through multi-tiered systems of support and restorative practices. While many started with innovations in specific schools and programs, these pilots were scaled with the goal of districtwide implementation.

Leaders sought to create professional learning that is ongoing, coherent, and personalized. All districts fostered lateral learning across campus teams to amplify and scale effective instructional practices. This involved investing in instructional leadership. For example, Pflugerville leaders created an area supervisor role to develop campus instructional leadership, and the new teacher leader positions in Edgecombe retained instructional expertise at the classroom level while supporting less experienced teachers.

Leverage Data to Drive Progress Toward Racial Equity

In schools serving more students of color—which have historically been underresourced and lower-performing—recent accountability measures that focused on low test scores led to punitive sanctions and school closures. Leaders in this study harnessed data differently to drive progress toward racial equity by assessing the conditions for learning, identifying the root causes of problems, and considering how changes in the system could improve equity. They routinized the collection of a wide range of data able to be disaggregated, used data to inform instructional practice, and reviewed data to evaluate and scale effective practices.

Routinize the Collection of a Wide Range of Disaggregated Data

Leaders reviewed many kinds of data addressing student outcomes, opportunities to learn, and qualitative input from students, educators, and community members. For example, Jefferson County leaders publicly report progress toward academic and climate metrics through an annual Envision Equity Scorecard and bimonthly “Vital Sign” reports. These data are disaggregated by “gap groups,” including African American, Hispanic, Native American, students with disabilities, students who receive free or reduced-price meals, and limited English proficiency student groups. In addition to monitoring quantitative metrics, leaders have sparked other ways to tell the fuller story of opportunity and outcome disparities. In Edgecombe, for example, campus staff conduct empathy interviews with students and families as part of regular instructional design cycles.

Use Data to Inform Instructional Practice

Leaders used data to demonstrate inequities and stimulate action. Superintendents empowered school leaders to analyze racially disaggregated academic achievement and growth data to inform instructional decision-making. To overcome fear of failure, leaders established learning cultures and paired high expectations with autonomy and robust instructional support from within or outside the district. Leaders in Pflugerville partnered with Education Equals Economics Alliance for instructional coaching in response to student growth data. Likewise, Edgecombe leaders partnered with the Southern Education Foundation’s Racial Equity Leadership Network and Transcend to redesign historically underperforming schools.

Review Evidence to Evaluate and Scale Effective Strategies

Leaders leveraged data disaggregated by race and ethnicity to define racial inequities, spur action, and refine reform efforts. The emphasis on “no random acts” in Hoke demonstrates this approach to continuous improvement. In Jefferson County, leaders developed a Racial Equity Analysis Protocol offering a set of questions that school and district leaders use to make decisions impacting students. They also emphasized the importance of responding to inequities with evidence-based instructional practices. In Jefferson County, the Accountability, Research, and Systems Improvement Division produced detailed literature reviews and evaluations of district proposals and initiatives to assess evidence of potential success and relationship with racial equity. Leaders and their teams traveled to other districts to observe and learn about innovative educational models at scale. Edgecombe leaders formalized a continuous improvement process in their Instructional Framework for Learning, which requires all educators to design, facilitate, reflect, and adjust instructional strategies. These data-responsive practices have enabled district leaders to expand, rather than ration, successful programs.

Acquire and Allocate Resources Equitably

Equity work requires leaders to mobilize resources: time, money, material resources, and human resources, including community partners, families, and staff. To allocate resources equitably, leaders had to disrupt patterns of concentrated investments in the most powerful and vocal groups within their communities. They invested in people first, pursued tenacious fundraising and grantmaking aimed at sustainability, made greater investments in greater areas of need, and expanded—rather than rationed access to—successful initiatives.

Invest in People First

Across all cases, leaders invested in building racially diverse and effective teacher workforces and leadership teams. They promoted talent internally and created pipelines to develop and support human capital for teaching and leading. Hoke Superintendent Williamson stated plainly, “We invest in people, not programs.” In addition to strategies to recruit and retain innovative educators, leaders invested in counselors, digital learning specialists, early childhood educators, multilingual coaches, school nurses, social workers, and school culture and climate specialists to advance holistic visions of student success.

Pursue Tenacious Fundraising Aimed at Sustainability

The districts in this study had vastly different budgets and expenditures; however, all pursued funding from the government, philanthropies, and local industries to sustain equity initiatives. For example, Edgecombe and Pflugerville secured state grants to establish Grow Your Own programs for aspiring educators in district high schools. Leaders in Edgecombe established a community foundation with the goal of creating an endowment that could sustain college scholarships for graduates. They worked to bring many innovations into the local budget over the long run.

Make Greater Investments in Greater Areas of Need

Understanding that gaps in opportunity drive gaps in outcomes, leaders invested additional resources in schools that had been historically underresourced. Edgecombe Principal Dr. Lauren Lampron explained:

One of the premises that we operate on is the idea that it’s not the achievement gap, it’s the opportunity gap. So, everything that we do, every lens that we look through is: What opportunity can we provide our kids so that they have the same access as students in other communities have?

For example, when Pflugerville leaders noticed staff leaving schools in the lower-income side of the district for positions in wealthier schools serving fewer students of color, they created need-based staffing ratios that reversed the pattern. Edgecombe Superintendent Bridges launched an Innovation Zone in the district’s most underresourced schools, investing to improve staff capacity and increase student access to rigorous, culturally relevant, project-based learning.

In addition to prioritizing historically underserved campuses, leaders concentrated resources to support historically underserved student groups. Examples include the Males of Color Academy in Jefferson County, Newcomer Academy serving immigrant students in Pflugerville, and the Hoke and Edgecombe Early College programs, which support students who would be among the first generation in their families to attend college. District leaders simultaneously worked to expand access to academic supports districtwide.

Expand, Rather Than Ration, Success

Leaders expanded access to educational opportunity by scaling effective academic programs and student services districtwide. In Hoke, an emphasis on “all means all” defined a whole-district approach to equalizing offerings and developing every school as a great school. In other districts, programs were strategically piloted, evaluated, adjusted, and implemented across schools.

All districts had some form of prekindergarten (PreK), advanced academic programming, multilingual supports, and inclusive behavioral supports. However, access to these kinds of educational experiences was inequitable. In cases like full-day PreK in Pflugerville or advanced teaching roles in Edgecombe, leaders reinvested resources to expand programs. To expand advanced coursework, leaders needed to eliminate structural barriers to entry, including middle school courses and examination fees, as well as artificial limits on the number and types of students who could participate.

Sustain Leadership Efforts Over Time

Leadership turnover threatens institutional knowledge and capacity to advance racial equity. Leaders established equity cultures and infrastructure designed to outlive their tenure and persist across future administrations. They cemented equity initiatives in district policy and organizational structures, developed cadres of equity-oriented leaders, and meaningfully engaged the community and school board.

Sustain Equity Initiatives Through Policy and Organizational Structures

Leaders introduced processes, policies, and structures dedicated to the work of advancing racial equity. The Jefferson County Diversity, Equity, and Poverty Division—led by a chief equity officer—provides the most robust example. This division, which has continued through the course of many superintendencies, has created resources for use throughout the district, including hiring screeners, decision-making frameworks, formative instructional evaluations, and ongoing data analyses that are aligned to the district’s racial equity commitment.

Structural reforms have enabled districts to pass the baton of racial equity leadership from one superintendent to the next. For example, both Edgecombe and Pflugerville revised their student codes of conduct to facilitate the implementation of trauma-informed, restorative behavioral practices. Reversing this policy would require action by the board of education and superintendent.

Develop a Cadre of Equity-Oriented Leaders

Rather than operating from the superintendent’s desk alone, leaders cooperated across offices and divisions and built collective capacity to advance racial equity at every level of the organization. These strategies developed institutional knowledge while creating equity leadership pipelines for succession planning. In Edgecombe and Hoke, superintendents cultivated equity-oriented teacher leaders, campus principals, and district staff to sustain the equity vision across a decade of leadership transitions.

Meaningfully Engage the Community and School Board

These cases demonstrated the persistence and collective power of communities invested in equitable educational opportunities and outcomes. Building on legacies of activism and positive political pressure, leaders engaged families, school boards, and community partners in the collective work to advance racial equity. For example, Jefferson County and Pflguerville leaders credited seasoned educators serving as board members as key levers for creating a core of equity leadership and key voices of public sentiment.

The Edgecombe Blue Ribbon Commission on Educational Equity elevated voices beyond those captured in routine community engagement. Hoke Superintendent Williamson garnered widespread community buy-in for the equity framework through regular, proactive engagement with families, community members, board members, school-level staff, district administrators, and local industry leaders. Indeed, effective racial equity leadership requires reciprocal relationships and collaboration throughout school districts and their communities to harness momentum, weather political storms, and gather key feedback to ensure each and every learner has the supports they need to thrive.

District Leadership for Racial Equity: Lessons From School Systems That Are Closing the Gap (brief) by Linda Darling-Hammond, Larkin Willis, and Desiree Carver-Thomas is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Southern Education Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.