Educating Teachers in California: What Matters for Teacher Preparedness?

Summary

Over the past decade, California has revised its standards for teacher preparation and credentialing and invested in high-retention pathways for entering teaching. As part of its new accreditation system, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) administers surveys to program completers who apply for their preliminary teaching credentials. This analysis examines survey responses of almost 60,000 completers from 2016–17 to 2020–21. California has a growing and increasingly diverse pool of teacher preparation graduates, and more than 90% rated their programs positively. Clinical support and access to subject-area preparation are strong predictors of overall feelings of preparedness. Graduates of new preservice residencies and student teaching programs report feeling better prepared than those entering as interns or on emergency-style permits. However, access to higher-rated programs offering more clinical support varies, with half of Black and Native American candidates, as well as most special education candidates, entering without access to student teaching.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

High-quality teacher preparation is a critical building block of an effective and stable teacher workforce. In California, the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) currently oversees teacher preparation programs (TPPs) at more than 100 institutions. These programs graduate more than 10,000 teacher candidates per year, almost one in 10 of the nation’s TPP completers. Over the past decade, California has considerably revised its standards for teacher preparation and performance expectations for beginning teachers. As part of its new accreditation system, the CTC administers surveys to TPP completers as they apply for their preliminary teaching credentials. The report on which this brief is based examined the survey responses of almost 60,000 completers from 2016–17 to 2020–21 as well as employers hiring these new teachers and cooperating teachers working with student teachers during their preparation.

Teacher Education Policy in California

California’s new teaching standards are focused on preparing teachers to develop students’ higher-order thinking skills, support social-emotional as well as academic learning, and effectively teach students with different language and learning needs.California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2020). Preliminary multiple subject and single subject credential preconditions, program standards, and teaching performance expectations; California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2016). California teaching performance expectations. The revised standards strengthened requirements for clinical practice and were incorporated into teacher performance assessments that evaluate how teachers can plan, implement, and assess instruction for diverse learners within subject matter contexts. In 2016, the CTC also implemented a new accreditation framework for TPPs that included new program standards, new outcome measures, and a new accreditation data system.California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2017). The Committee on Accreditation’s Annual Accreditation Report to the Commission on Teacher Credentialing, 2016–17.

The program completer surveys introduced as part of this new framework are meant to serve as a tool for continuous improvement for programs (which receive the data from the CTC) and input for accreditation decisions. In other contexts, teachers’ ratings of how well they were prepared have been found to be associated with candidates’ later evaluation ratings, effectiveness in promoting student learning gains, and retention.Bastian, K. C., Sun, M., & Lynn, H. (2021). What do surveys of program completers tell us about teacher preparation quality? Journal of Teacher Education, 72(1), 11–26.

Meanwhile, following a long decline in TPP enrollment, shortages of teachers began to re-emerge in California by 2015.Carver-Thomas, D., Kini, T., & Burns, D. (2020). Sharpening the divide: How California’s teacher shortages expand inequality. Learning Policy Institute. In 2016–17, the number of substandard credentials issued in the state outpaced the number of new preliminary credentials issued to teachers prepared in California TPPs. The state has since invested in new program models—like teacher residencies—and service scholarships to stem shortages and strengthen preparation. These investments total more than $1.4 billion since 2016 and reflect a substantial increase in education funding statewide. As noted below, a large increase in the number of fully prepared recruits into teaching—and in the number of candidates of color—suggests that these investments may be paying off.

Pathways to Teaching in California

In California, three primary pathways are available to people who want to become teachers:

- completing a preservice teacher preparation program (TPP) with supervised student teaching or residency under the guidance of a cooperating or mentor teacher before serving as a teacher of record;

- participating in an internship program in which candidates who have already demonstrated subject matter competency complete their preparation program while serving as a teacher of record; or

- entering teaching with an emergency-style permit, authorized by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) if a district cannot fill the vacancy with a fully credentialed teacher, and subsequently enrolling in a TPP to earn a credential.

Of the more than 100 institutions currently approved by the CTC for teacher preparation, approximately 80 are institutions of higher education (IHEs) and 25 are local education agencies (LEAs) that run their own preparation programs. California has recently invested in teacher residencies, which are run by IHEs in partnership with LEAs and provide a full academic year of subsidized clinical training while candidates complete credential coursework. As of 2020–21, about 10% of the CTC’s program completer survey respondents reported participating in residencies, and 60% of responding residency completers were teachers of color. In addition, 61% of responding completers in 2020–21 reported participating in student teaching programs and 25% in internships.

California currently offers preliminary credentials for multiple subject teachers (i.e., teaching multiple subjects, typically within elementary or middle schools), single subject teachers (i.e., teaching specific subjects, typically in middle or high schools), and education specialists (i.e., teaching students with disabilities at any grade level).

Source: The percentages presented above are calculated based on program completers’ responses on the 2020–21 Commission on Teacher Credentialing survey. These percentages do not include completers who did not appear in the survey data or who did not answer this specific question (about 6% of all respondents from the 2020–21 survey).

California’s Pool of Recently Prepared Teachers Is Growing in Size and Diversity

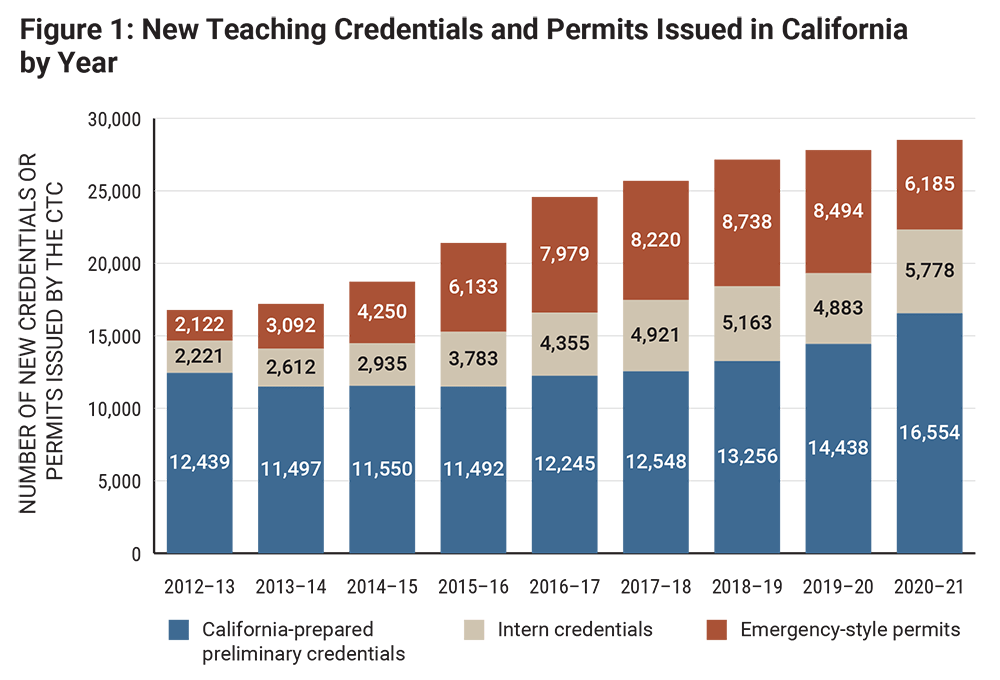

The pool of recently prepared graduates from California TPPs has increased in size and racial/ethnic diversity. According to the CTC’s California Educator Supply dashboard, the number of completers from California TPPs applying for a new preliminary teaching credential increased by 35% from 12,245 completers in 2016–17 to 16,554 completers in 2020–21.Calculated from CTC’s annual data on new preliminary teaching credentials issued by segment and credential name. See California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2022). Teacher supply: Credentials. As shown in Figure 1, the number of preliminary teaching credentials issued by the CTC has been increasing since 2016–17. In the two years following 2018–19, when many of the new state investments were beginning to be implemented, the number of fully prepared new entrants increased by about 3,300, while the number of emergency-style permits decreased by about 2,500. During this time, California both enacted supports and subsidies for teacher candidates and temporarily suspended certain assessment requirements for those seeking credentials or permits as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase represents a break from prior trends, in which the number of newly credentialed teachers had been dropping for over 10 years.Darling-Hammond, L., Sutcher, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Teacher shortages in California: Status, sources, and potential solutions. Learning Policy Institute. Nationally, the number of individuals completing TPPs decreased by 22% between 2012–13 and 2018–19, and California was one of only eight states with increases during that period.U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education. (2022). Preparing and credentialing the nation’s teachers: The Secretary’s 11th report on the teacher workforce.

Source: California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2022). California Educator Supply.

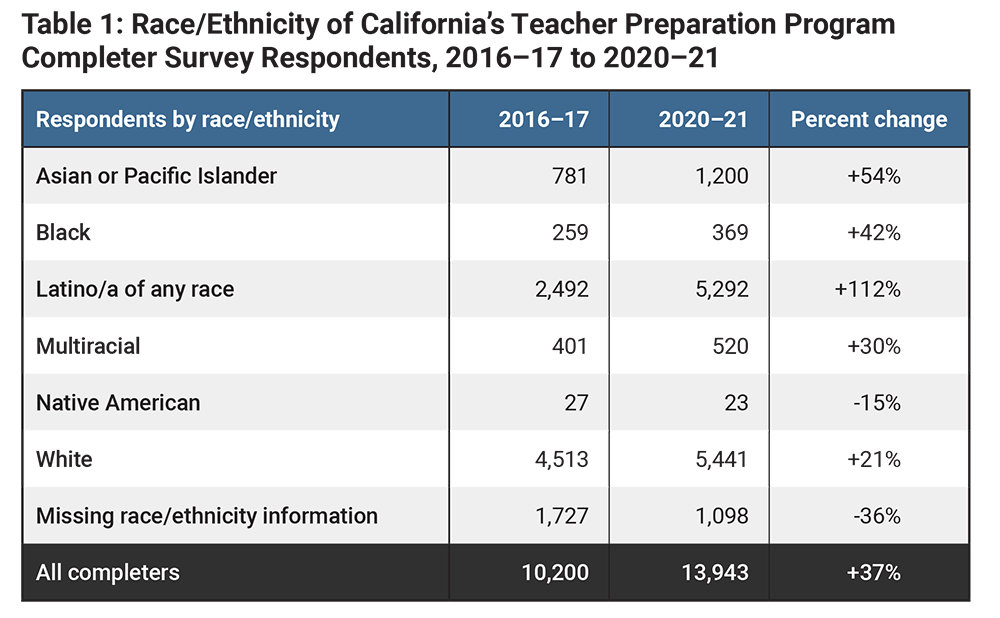

Information provided by completers in the CTC’s program completer survey also shows how the composition of the teacher pipeline has changed.Figure 1 includes all credentials issued by the CTC as reported in the California Educator Supply dashboard and annual reports. In contrast, the remainder of the report presents data for 59,140 California TPP completers who responded to the CTC’s program completer survey between September 2016 and August 2021, which represents an estimated 84–90% of all California-prepared teachers applying for their preliminary teaching credential each year. Notably, there was a 53% increase in completers with more in-depth preservice preparation, including student teaching and residency programs, between 2016–17 and 2020–21. There also have been demographic shifts in this group, with a growing share of survey respondents identifying as people of color. In particular, the number of Latino/a candidates has more than doubled between 2016–17 and 2020–21, as shown in Table 1. As of 2020–21, 53% of survey respondents were teachers of color, compared to 39% in 2016–17. Nationally, just 27% of recent completers identified as people of color.U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education. (2022). Preparing and credentialing the nation’s teachers: The Secretary’s 11th report on the teacher workforce.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of Commission on Teacher Credentialing Program Completer Survey data (2023).

Most Graduates Felt Well Prepared by Their Programs

Preparation program completers rate their preparation highly, with 90% of completers rating their TPPs as effective or very effective across all 5 years of the survey data. Employers and cooperating teachers, responding to the surveys administered between 2018–19 and 2020–21 and representing a smaller number of TPPs, also had positive perceptions of programs that largely aligned with completers’ impressions. About 80% of responding cooperating teachers rated the TPPs that they worked with as effective or very effective, and two thirds of employers reported that specific TPPs they hired teachers from were preparing those teachers “well” or “very well.”

All three groups were asked to rate how well TPPs prepared completers to engage in specific teaching performance expectations (TPEs) aligned with California’s Standards for the Teaching Profession (CSTP). All three groups rated preparation for creating and maintaining an effective learning environment for students highly. In contrast, relatively fewer completers reported feeling well prepared to work with families. Completers, cooperating teachers, and employers also rated preparation in the following areas less highly: (1) supporting English learners, (2) supporting special learning needs, and (3) involving students in self-assessment.

Program Ratings Are Related to Clinical Support and Coursework

Completers’ perceptions of preparedness were strongly related to the nature of their clinical experiences and their opportunity to learn how to teach reading, writing, and math. Overall, completers from preservice preparation programs had more positive perceptions of their preparation than those completing their preparation while teaching. Across the 5 years of survey data, 56% of student teachers/residents rated their TPPs as very effective compared to 48% and 47% of completers who participated in internships or completed their preparation on an emergency-style permit.

Completers from preservice preparation programs had more positive perceptions of their preparation than those completing their preparation while teaching.

Importance of Clinical Support

Prior research on teacher preparation highlights the importance of the clinical experience in preparing effective teachers, especially sustained field experiences that allow for practical application of TPP coursework and field support from effective educators.Boyd, D. J., Grossman, P. L., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2009). Teacher preparation and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31(4), 416–440; Ronfeldt, M. (2021). Links among teacher preparation, retention, and teaching effectiveness. National Academy of Education Committee on Evaluating and Improving Teacher Preparation Programs. National Academy of Education. In this study, both the number of hours of student teaching and the amount of clinical support (e.g., being observed and getting feedback on teaching) varied considerably across programs.

California’s Requirements for Clinical Practice

Preparation coursework and clinical experiences are structured differently across pathways into teaching. Clinical experiences for student teachers and residents occur prior to completion of their preparation and before they become teachers of record (i.e., preservice). In contrast, internship programs require a shorter period of preparation before entering the classroom as a teacher of record, and much of the preparation experience occurs while program participants are already working as teachers in California schools.

Hours of clinical practice: The CTC requires that candidates, regardless of pathway, complete at least 600 hours of clinical practice over the course of their programs. The CTC survey asks completers to estimate how many hours they spent in student teaching as part of their supervised fieldwork. Despite the CTC requirements outlined above, 49% of student teachers and 30% of residents surveyed in 2020–21 reported fewer than 600 hours of student teaching. The survey does not currently include questions that allow a similar calculation for intern or other program completers, who constitute 29% of total respondents.

Clinical support: The CTC’s program standards indicate that each TPP must employ trained program supervisors to formally observe and evaluate candidates at least six times per semester and district-employed supervisors (i.e., cooperating or mentor teachers) to provide at least 5 hours of support and guidance per week. The CTC survey asks about these clinical supports, and there is considerable variation in the amount of support reported. As an example, 19% of completers indicated that they received instructional feedback from program staff five times or fewer, while 20% reported receiving feedback more than 15 times. In 2020–21, residents were more likely than student teachers to report high levels of program feedback and observation. When asked about their cooperating or mentor teachers, student teachers and residents were more likely to report supportive behavior (e.g., observing teaching and offering feedback) than interns. For example, 89% of student teachers/residents reported that their cooperating teacher modeled effective practice, while 66% of interns said their mentor teacher did the same.

Source: California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2020). Preliminary multiple subject and single subject credential preconditions, program standards, and teaching performance expectations.

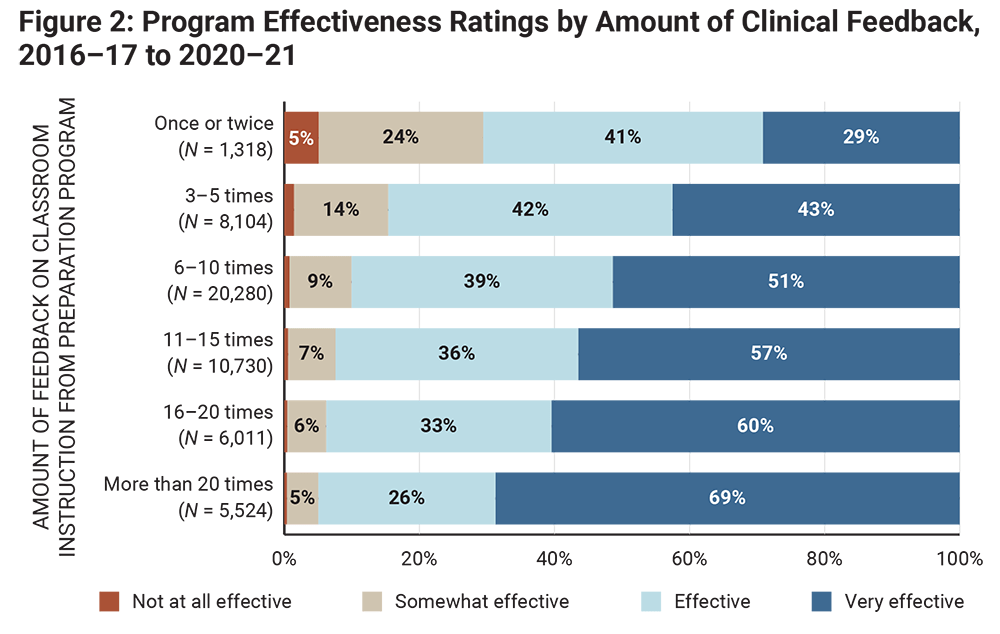

The nature and extent of clinical support from TPPs was strongly related to completers’ feelings of preparedness and employers’ views of program quality. For example, Figure 2 shows how program completers reporting that their program offered feedback on their clinical practice five times or fewer—19% of all completers—were much less likely to rate their TPP as very effective compared to completers with more support. Completers also had more positive assessments of their preparation when they had cooperating/mentor teachers who frequently observed teaching and offered feedback, helped plan and organize curriculum materials, and supported in other ways. Employers also rated more highly those institutions in which completers reported having more clinical support.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of Commission on Teacher Credentialing Program Completer Survey data (2023).

Importance of Preparation for Teaching Reading, Writing, and Math

Training in how to teach in specific content areas—often referred to as pedagogical content knowledge—is also a critical component of teacher preparation, and candidates’ exposure to certain content and pedagogy coursework can predict teachers’ eventual effectiveness.Loewenberg Ball, D., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407; Ronfeldt, M. (2021). Links among teacher preparation, retention, and teaching effectiveness. National Academy of Education Committee on Evaluating and Improving Teacher Preparation Programs. National Academy of Education. In California, the CTC has established subject-specific pedagogical skills for all beginning teachers. In their surveys, multiple subject (i.e., elementary teachers) and education specialist (i.e., special education teachers) completers were asked about their training to teach reading, writing, and math.

When asked about their opportunity to learn elements of teaching reading, writing, and math, at least 75% of respondents reported that their program had “spent time discussing or doing” each teaching element, such as learning foundational reading skills and learning how to adapt math lessons for students with diverse needs. Student teachers and residents were more likely to report opportunities to learn each aspect of reading, writing, and math teaching than interns or those finishing their preparation while working on an emergency-style permit. Completers who reported having an extensive opportunity to learn all aspects of reading, writing, and math teaching were much more likely to rate their TPP as very effective and to describe themselves as well prepared overall.

Access to Highly Rated Preparation Is Unequal

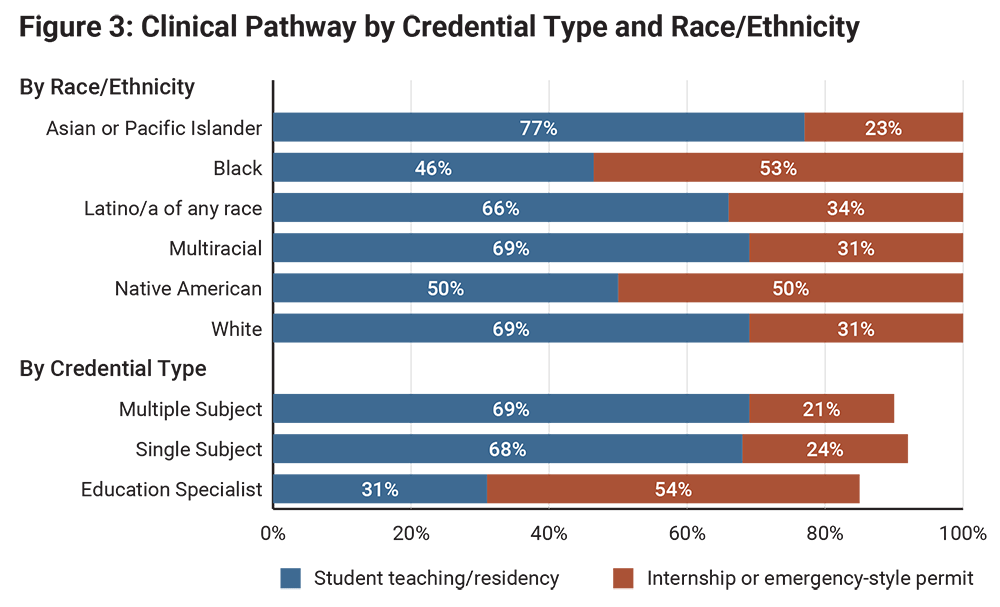

Not all completers reported equal access to the preparation experiences associated with higher ratings of program effectiveness and more positive perceptions of preparedness. Notably, access to preservice clinical experiences (i.e., student teaching or residency programs) varied considerably by race/ethnicity and credential type. As shown in Figure 3, only 46% of Black and 50% of Native American completers reported participating in student teaching or residencies, compared to at least two thirds of all other racial/ethnic groups. Fewer than one third of education specialists (i.e., special education teachers) participated in student teaching or residencies, as compared to about 7 in 10 multiple subject completers (i.e., elementary teachers) and single subject completers (i.e., secondary teachers). Education specialists were also more likely to report limited student teaching hours or low levels of clinical support from their TPPs.

Policy Considerations

The findings from this analysis of 5 years of TPP completer data suggest that California’s recent policy changes to strengthen teacher preparation and increase the supply of well-prepared teachers may be paying off. The number of new California preliminary credentials increased by 35% between 2016–17 and 2020–21, with a sharp increase after 2018–19, and newly prepared teachers are more racially/ethnically diverse. While TPP completers generally report feeling well prepared, some are getting strong clinical experiences, in which they have sustained clinical placements and support, and others are not. The results suggest several steps that California policymakers and practitioners can take to further strengthen teacher preparation:

- Continue to expand and improve access to high-quality preparation experiences and pathways, especially for education specialists and for historically underserved candidates of color. California should continue supporting the strong implementation of the state’s recent investments meant to substantially cover the cost of preparation for teacher candidates who commit to teaching in high-need schools, including Golden State Scholarships, subsidies for classified staff to become teachers, and teacher residencies, especially for teachers in shortage fields like special education. These programs are diversifying and strengthening the teacher workforce. Given the impact of student debt on candidates’ preparation choices, especially for candidates of color, the state might also consider increasing support to financially needy teacher candidates and leveraging new federal funding under the Higher Education Act to expand TPPs at Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs). The state might also leverage state and federal funding to support high-quality apprenticeships into teaching, which allow candidates to earn while they learn, receiving pay while they gain teaching skills under the supervision of a cooperating or mentor teacher and take coursework to earn their preliminary teaching credential. A more robust state recruitment and communication strategy could help potential teacher candidates understand the full array of financial supports available to them as well as the different pathways into teaching, so they can afford to choose the pathway that is right for them.

- Increase opportunities for teacher candidates to learn how to work with families and support the needs of English learners (ELs) and students with disabilities (SWDs) by deepening coursework and clinical learning opportunities, supporting TPPs in redesigning their programs, and expanding access to dual credential programs. Working with families and supporting students who have particular learning needs are areas that typically require deeper and more focused clinical experiences, as well as integrated coursework. The CTC and teacher education networks can encourage the exchange of information and exemplars. The state could also incentivize the creation or expansion of integrated and dual credential programs, in which candidates earn a dual credential or endorsement that provides additional, specialized preparation to meet the needs of ELs and/or SWDs.

- Strengthen access to high-quality preparation by improving the quality of all pathways through the implementation and enforcement of CTC’s new accreditation framework. Both clinical support and opportunities to learn English language arts and math foundations were strongly related to completers’ perceptions of preparedness, but not all completers reported having these opportunities. For example, the amount of clinical support reported by completers varies considerably across institutions, and there are some institutions with substantial proportions of completers reporting limited clinical observations or feedback. These findings suggest a need for continued efforts to strengthen the implementation and enforcement of CTC’s new accreditation framework as well as the newly adopted education specialist program standards and literacy standards. For example, institution-level survey results can be used to flag programs for further review or support.

- Support TPPs in using their survey data for continuous improvement. This survey data can be leveraged as part of the program accreditation process to identify struggling programs as well as provide an additional tool for TPPs to support continuous improvement. The CTC, along with other organizations based at universities and nonprofits, can help support TPPs to use this data—and other metrics of program effectiveness—to guide programmatic decision-making and continuous improvement.

Finally, California’s recent efforts to strengthen its teacher preparation systems offer a valuable example for other states hoping to redesign preparation standards or integrate surveys into the evaluation of TPPs. California’s approach to surveys highlights some important best practices, including how to (1) integrate completer surveys into the state’s teacher licensure process, (2) align surveys to statewide standards for teaching, (3) administer surveys to all completers across preparation pathways, and (4) build statewide capacity for data use by offering results in multiple forms. This approach ensures that survey results can offer helpful perspectives on teacher preparation across the state that can support both accreditation processes and continuous improvement efforts.

Educating Teachers in California: What Matters for Teacher Preparedness? by Susan Kemper Patrick, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Tara Kini is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Report originally published March 2, 2023 | Document last revised April 27, 2023