Leveraging Resources Through Community Schools: The Role of Technical Assistance

Summary

Community schools are an evidence-based strategy to advance a “whole child” approach to education by offering integrated student supports (e.g., health care or housing assistance), expanded and enriched learning time, family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership and practices. This brief examines how local government and nonprofit agencies in two California counties—Los Angeles and Alameda—have provided technical assistance to support community school initiatives.

Evidence from these two counties indicates that (1) county offices are well-positioned to form cross-sector partnerships that efficiently integrate a comprehensive suite of services in local schools; (2) cross-sector partnerships are strengthened by a shared vision and clear agreements among partners; and (3) a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) and a Coordination of Services Team (COST) can help partners coordinate, deploy, and target their resources efficiently at school sites.

Introduction

Research grounded in the science of learning and development tells us that in order to achieve more equitable educational outcomes, schools should attend to students’ academic, social, and emotional growth as well as to their healthy physical development and mental wellness.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Community schools are designed to bring together a comprehensive range of services and resources at the school site in response to these “whole child” needs. By coordinating academic, mental health, physical wellness, and social-emotional supports, community schools contribute to a whole child approach to education. This brief presents examples from California that show how technical assistance from county agencies and nonprofits can bolster the capacity of community school initiatives to design schools that can effectively respond to students and families.

The community schools strategy is more relevant than ever during the time of COVID-19, as unemployment rates skyrocketLong, H., & Van Dam, A. (2020, May 8). U.S. unemployment rate soars to 14.7 percent, the worst since the Depression era. Washington Post. and many parents, especially those from lower-income communities, report concerns that their children will fall behind academically as a result of school closures.Horowitz, J. (2020). Lower-income parents most concerned about their children falling behind amid COVID-19 school closures. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; The Education Trust–West. (2020, April 30). Poll: Coronavirus crisis puts parents’ and young children’s well-being at risk [Press release] (accessed 6/10/20). Community schools—which are growing in popularity across California, with initiatives present or emerging in Los Angeles, Oakland, and many other districts—are especially well-positioned to meet the myriad needs of students and families during this crisis.Partnership for the Future of Learning. (2018). Community schools playbook. Washington, DC: Author. By providing a well-coordinated and comprehensive set of supports, even in a distance learning environment, community schools can help respond to the digital divide and address essential supports such as food delivery and health care.Quartz, K. H., & Saunders, M. (2020, May 14). Community-based learning in the time of COVID-19 [Blog post] (accessed 05/14/20); Baron, K. (2020, April 30). Triaging trauma: Community schools tap partners to address needs made worse by COVID-19. Education Dive; Sarikey, C. (2020, June 18). School-based health centers: Trusted lifelines in a time of crisis [Blog post] (accessed 06/18/20).

What Is a Community School?

A community schoolInformation in this section comes from the following sources: Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; California Department of Education. (n.d.). County community schools (accessed 05/15/20); California Department of Education. (n.d.). Community day schools (accessed 05/15/20). is both a place and a set of partnerships between the education system, the nonprofit sector, and local government agencies. While the specific programs and services vary according to local context, there are four key pillars of the community school approach.

- Integrated student supports—includes mental and physical health care, nutrition support, housing assistance, and other wraparound services.

- Expanded and enriched learning time—includes lengthening the school day and year, as well as enriching the curriculum through real-world learning opportunities.

- Active family and community engagement—includes both service provision and meaningful partnership with parents and family members to support children’s learning.

- Collaborative leadership and practices—includes coordination of community school services as well as site-based leadership teams and teacher learning communities.

Community schools as discussed in the brief are distinct from “county community schools” and “community day schools,” which are alternative schools in California operated by county offices of education and districts, respectively. These alternative schools are designed to serve students who have been expelled from school or are referred because of behavior or attendance problems.

When implemented well, community schools are grounded in an evidence base showing improvement in student outcomes, including attendance, academic achievement, high school graduation rates, and reduced racial and economic achievement gaps.Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Johnston, W. R., Engberg, J., Opper, I. M., Sontag-Padilla, L., & and Xenakis, L. (2020). What is the impact of the New York City community schools initiative? New York, NY: City of New York. This research shows that longer-operating and better-implemented programs yield more positive results. The specific features that indicate effective implementation of community schools have not been fully studied, although standards widely endorsed by practitioners show the importance of having a full-time dedicated staff member (often called a “community school coordinator”) to coordinate services that might otherwise be unavailable or difficult to access.Coalition for Community Schools. (2018). Community school standards. Washington, DC: Institute for Educational Leadership; Coalition for Community Schools. (2018). Standards for community school initiatives. Washington, DC: Institute for Educational Leadership.

Technical assistance can support high-quality implementation of community school initiatives. For the purposes of this brief, the definition of “technical assistance” includes the various supports needed to launch and sustain community school initiatives at scale, such as professional development and coaching, support for strategic planning, and partnership development that brings resources to schools (e.g., direct staffing, service provision, and funding).

Districts that are focused on systemwide community school initiatives—such as Cincinnati, Los Angeles, New York City, and Oakland—can play the role of technical assistance providers.Partnership for the Future of Learning. (2018). Community schools playbook. Washington, DC: Author. Some state initiatives, such as New York’s approach to providing community school funding to all high-poverty schools, offer technical assistance through regional units based at universities.New York State Community Schools Technical Assistance Centers. (n.d.). Home page (accessed 06/01/20). This brief shows how counties can connect and support community schools in productive networks that access needed resources effectively. It focuses on how two California counties, Los Angeles County and Alameda County, have provided crucial support for developing and sustaining community school initiatives. Based on interviews with staff at county agencies, administrators at nonprofit and community-based organizations, and district- and school-level leaders, we describe the nature of county-level support for community school initiatives and distill key lessons learned.

How Is New York State Supporting Community Schools?

New York state has developed a robust infrastructure to support the development and sustainability of community school initiatives.Information in this section comes from the following sources: Interviews with staff from the New York State Community Schools Technical Assistance Centers, Central/Western New York and New York City (2020, February–April); Partnership for the Future of Learning. (2018). Community schools playbook. Washington, DC: Author; Cuomo, A. M., & Mujica, R. F, Jr. (2020). FY 2021 enacted budget financial plan. Albany, NY: New York State Division of the Budget; Cuomo, A. M., & Mujica, R. F, Jr. (2019). FY 2020 enacted budget financial plan. Albany, NY: New York State Division of the Budget; The University of the State of New York. (2016). Guidance document: Foundation Aid: Community Schools set-aside 2016–17 enacted state budget. Albany, NY: Author. Over the past 4 years, the state has annually set aside increasing amounts of its school funding formula, from $100 million in 2016–17 to $250 million in 2019–20, which the state maintained in its enacted 2020–21 budget. This funding can be used to support community schools in districts identified as high-need. In addition to supporting new community school initiatives, set-aside dollars can be used to sustain existing community school programs that had been funded under a prior Community Schools Grant Program (a 2-year initiative that began in 2013 and provided 3-year grants of $500,000 each to eligible school districts).

Additionally, through a 5-year grant (approximately $5 million in total), the state has funded three Community Schools Technical Assistance Centers (CSTACs): the New York City CSTAC, the Central/Western CSTAC, and the Eastern CSTAC. These centers were created for the sole purpose of supporting community schools in the state, and they report directly to the State Department of Education. The CSTACs provide a range of opt-in supports to community school initiatives within their region, such as professional development for community school practitioners via webinars and conferences; site visits to provide in-person coaching; working with district and school leaders to build capacity through implementation and improvement science approaches; and maintaining a database of community partners, programs, and resources that can support community schools. The CSTACs also build regionwide communities of practice to highlight best practices and to provide opportunities for practitioners within the region to support and learn from one another.

Los Angeles County

Located in Southern California, Los Angeles County (LA County)Information in this section comes from the following sources: Interviews with staff from the Los Angeles County Office of Education (2020, September–April); United States Census Bureau. (2020, March 26). County population totals 2010–2019; Los Angeles County Office of Education. (n.d.). Community schools (accessed 05/11/20); County of Los Angeles Public Health. (n.d.). Promotores Program (accessed 05/11/20). is the most populous county in the United States, with over 10 million inhabitants in 2019. The Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) leads a community school pilot initiative, which launched in September 2019 in an effort to improve the academic, social-emotional, and physical well-being of students. The pilot is currently underway in 15 districts that have each selected one high school for participation. The immediate focus is on providing county resources for integrated student supports, as well as some expanded learning opportunities, particularly for youth in foster care and those experiencing homelessness. The long-term goal is to meaningfully engage families and community partners through a collaborative process and to enrich the curriculum through a focus on college and career preparation and teaching and learning. This section primarily describes key county- and school-level features of the LACOE initiative.

However, other community school initiatives are also underway in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LA Unified), the second-largest school district in the country (behind New York City). These initiatives are supported by the district rather than LACOE. The LA Unified initiative, launched in 2019, includes a plan to convert 30 schools over the next 2 years into community schools with full-time, on-site coordinators and additional health supports and services for students and families.Los Angeles Unified School District. (2017, June 13). Embracing community school strategies in the Los Angeles Unified School District [Press release] (accessed 05/15/20); Freedberg, L. (2019, January 22). Los Angeles teachers return to class after voting to end strike. EdSource. Alongside this district initiative, the LA County Department of Mental Health (DMH) has allocated funds to the district for an additional effort focused on early education and services for children ages 0 to 8.Interviews with staff from the Los Angeles Unified School District and the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (2020, May). Funding from multiple sources supports this work, including First 5 and the Mental Health Services Act (allocated by DMH). These funds are used to train social workers and resource navigators to coordinate services at early childhood centers and nearby elementary schools, and to implement trauma-informed practices, support the development of self-regulation skills in young children, and engage families. The mental health team has also received extensive training in early childhood mental health consultation.

LA County Office of Education: Key Central Office Supports

LACOE has supported its community school pilot with multiple levels of technical assistance. There are three central positions based in the county office of education: the director of community schools (who oversees the initiative) and two county-level coordinators, who are responsible for supporting pilot sites. Initial funding came from DMH (through the state’s Mental Health Services Act) and the LA County Board of Supervisors, as well as private philanthropy. The LA County Executive’s Office has also supported the initiative. This high-level buy-in from county leadership was codified through a series of memorandums of understanding and played a key role in advancing the pilot.

The support for participating districts and schools began early on, with LACOE pilot staff meeting with school and district leaders to conduct outreach and better understand local priorities. Specifically, the county office provided technical assistance by engaging the districts in a needs and assets mapping process, which revealed that student mental health, support for students in foster care, and support for students experiencing homelessness were top priorities across the pilot. In addition, LACOE asked each of the 15 participating high schools to identify three to five priorities and create school profiles to identify assets and needs or gaps in service. This process of assessing district and school assets and needs helped guide LACOE’s pursuit of resources and partnerships with other county agencies.

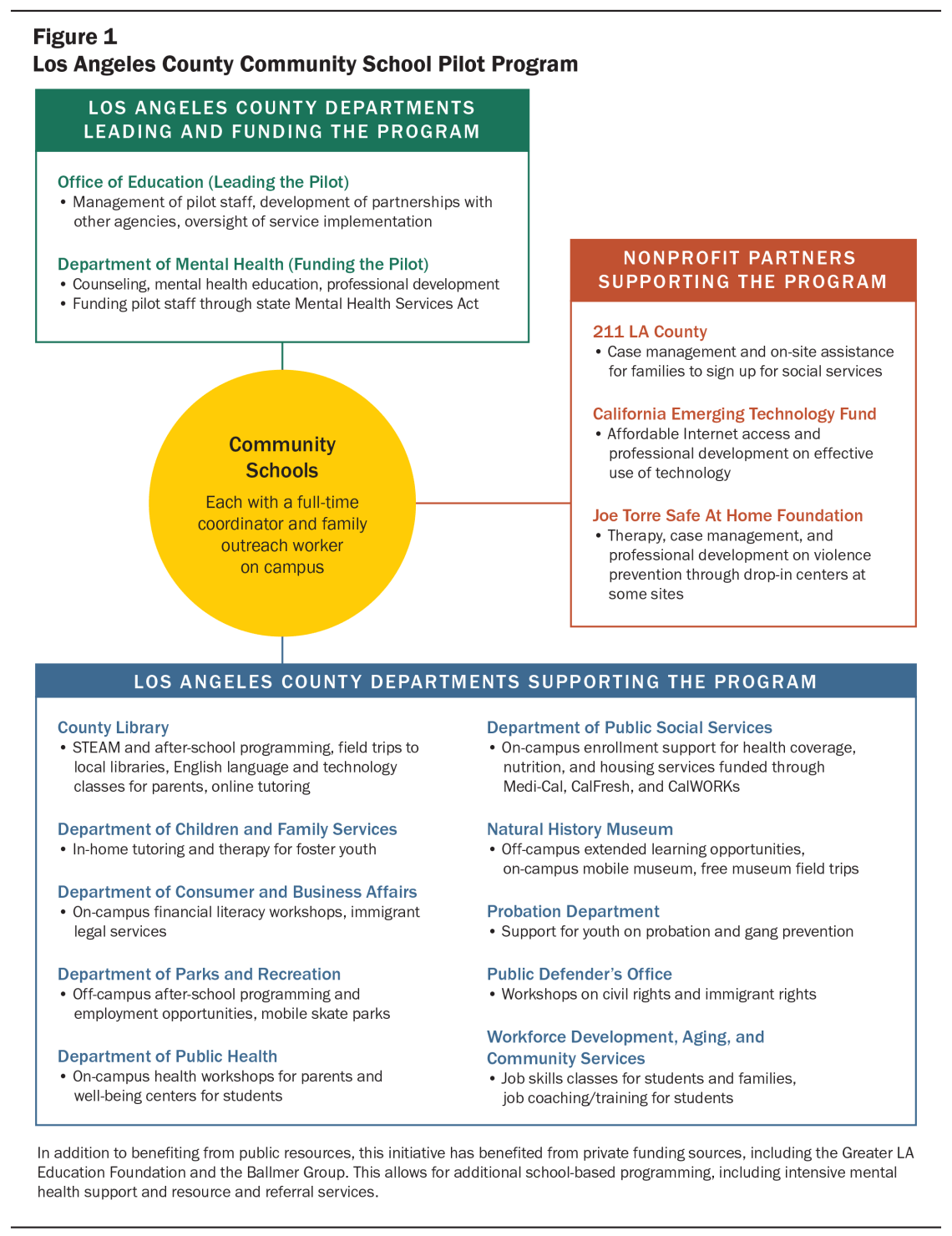

To date, LACOE has established key partnerships with a number of county and nonprofit agencies that have offered to provide services to participating schools—another form of technical assistance. Pilot staff reported that establishing these cross-sector partnerships at the county level can help the collaborating agencies serve children and families more efficiently, as well as satisfy the metrics associated with various funding sources (e.g., hitting enrollment targets for programs such as Medi-Cal and CalFresh). These partnerships can also help to address the community school pillars, including integrated student supports, expanded and enriched learning time, and active family and community engagement. Prominent cross-sector partnerships include:

- Preventive mental health services for students and families through the LA County Department of Mental Health (DMH). This includes presentations on mental health and healthy relationships at school resource fairs, along with professional development on social-emotional well-being for school staff. LACOE and DMH share a mutual focus on strengthening interventions through the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) approach, “a whole-school, data-driven, prevention-based framework for improving learning outcomes for every student through a layered continuum (typically three tiers) of evidence-based practices that increases in intensity, focus, and target to a degree that is commensurate with the needs of the student.”California’s Statewide Task Force on Special Education. (2015). One system: Reforming education to serve all students. Sacramento, CA: Author (accessed 05/11/20). DMH had existing partnerships in place with many of the participating schools to provide individual and group therapy and case consultation to students. The LACOE pilot plans to build on those existing partnerships by working with DMH to provide Tier 1 preventive services for the school community, such as mental health trainings for students, families, and staff.

- On-campus information and enrollment options for social services through the LA County Department of Public Social Services (DPSS). DPSS plans to offer enrollment support at pilot sites to students and families who are eligible for Medi-Cal health coverage, CalFresh nutrition support, In-Home Supportive Services, and CalWORKs housing services. DPSS is also supporting students and families who do not qualify for Medi-Cal to sign up for other health care options. This is key to ensuring that all students are able to access Tier 1 mental health services, as well as physical health care, as needed. School-level LACOE pilot staff will support the enrollment process and follow up as needed to ensure that students and families are able to access off-site services.

- On-campus wellness services through the LA County Department of Public Health (DPH). These wellness services include Promotores community health workshops focused on nutrition education. Wellness centers (called Wellbeing Centers), offered through DPH, are also planned at six to seven of the community school pilot sites. The wellness centers, part of a broader DPH initiative to establish wellness centers at schools throughout LA County, will offer mental health services, substance abuse prevention, peer advocacy and leadership classes, reproductive education and health care, and basic health services such as vaccinations.

Prior to COVID-19-related school closures, participating school and district staff met with representatives from 12 different LA County agencies for a series of networking conversations. Additional partners that were identified in those meetings include the LA County Department of Consumer and Business Affairs; LA County Library; LA County Probation Department; LA County Department of Children and Family Services; LA County Public Defender’s Office; LA County Department of Parks and Recreation; Natural History Museum of LA County; and LA County Workforce Development, Aging, and Community Services. These agencies plan to offer a range of services that are not presently available at participating school sites, from financial literacy and immigrant rights workshops to mobile STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, and math) programming and on-site skate parks.

Nonprofit partners, including 211 LA County, the California Emerging Technology Fund, and the Joe Torre Safe At Home Foundation, are also playing important roles in the pilot. For example, the Joe Torre Safe At Home Foundation plans to support centers at five pilot sites that offer drop-in group and individual therapy, case management services, schoolwide awareness campaigns, and staff professional development focused on trauma and violence prevention.

LA County Office of Education: Key School Site Supports

Each of the 15 pilot high schools receives funding from LACOE for two full-time positions. Each school is staffed with a program specialist (referred to here as a community school coordinator). The coordinator is responsible for overseeing the implementation of the county and nonprofit services described above, which are aligned with school site needs. This is a certificated position that requires at least 3 years of teaching or social work experience. Additionally, each pilot school has a full-time educational community worker, a position responsible for family outreach that does not require a teaching credential.

What Does a LACOE Community School Look Like in Action?

Because the LACOE pilot is relatively new, and most community school coordinators were in place only 3–4 months before schools were closed due to COVID-19, they focused mainly on conducting an inventory of existing services and needs at their sites, as well as strengthening the coordination of existing programs, such as on-site counseling and other mental services.Information in this section comes from an interview with staff from the Los Angeles County Office of Education (2020, April 6). For example, Nathalie Umaña started her position as the LACOE coordinator at Duarte High School (Duarte High) in January 2020. Duarte High is a midsize high school with approximately 800 students, 75% of whom qualify for free or reduced-price meals. Nathalie began her work by reviewing school data and examining assets and needs at the site. In doing so, she identified a lot of resources available on campus but found that they were not being fully utilized. In response, Nathalie organized a Coordination of Services Team (COST) that meets regularly to assess students’ needs and connect them with appropriate services. She also created a process for teachers to easily refer students in need of services to the COST.

Nathalie had just begun the process of implementing additional integrated student supports and expanded learning opportunities, such as mental health services and county library programs, when schools closed in response to COVID-19. She was also initiating the launch of an advisory council to bring together Duarte High community members and school site leaders to look at data and identify high-priority supports—an example of collaborative leadership. Doing so will bring the site closer to having the full suite of integrated student supports (such as physical and mental health care and social services), expanded learning opportunities, family engagement practices, and collaborative leadership structures, that are typically associated with the community school pillars.

Due to the school’s temporary closure, Nathalie pivoted her efforts to address the urgent needs of students and families brought about by COVID-19. For example, she worked with colleagues to create a tracker of every student (including their home language and parent phone numbers) and divvy it up among school staff to ensure that all Duarte High students would receive a check-in phone call. She also worked with colleagues to create a script for the phone call with questions to assess family needs and their level of connectedness with school staff. Responses were tracked using the school’s online student information system (Aeries) and guided the school’s distribution of resources, such as hot spots for internet access. Nathalie and the Duarte High team also created a resource guide and an associated social media campaign for families in response to the school closure. The campaign used Instagram to provide daily school announcements (over 600 students tuned in each day), “senior spotlights” to celebrate college acceptances, birthday shout-outs, and a “resource of the day” drawn from the resource guide. Finally, Nathalie worked with school staff to arrange virtual office hours to support parents with digital learning.

As the pilot continues during the 2020–21 school year, LACOE staff expect to oversee the expansion and implementation of the services described above and to develop new partnerships that capitalize on local assets and respond to the needs of participating schools. This will further transform the pilot sites into fully functioning community schools that address the four pillars and are equipped to meet the academic, physical, mental, and social-emotional needs of students and families through a combination of county and local supports. The LACOE pilot shows how technical assistance for community school initiatives can involve coaching for school staff, strategic planning support for districts and schools, and development of county-level partnerships that bring resources—including services, funding, and staffing—to schools.

Alameda County

Located on the east side of San Francisco Bay, AlamedaInformation in this section comes from the following sources: Interviews with staff from the Alameda County Office of Education, Alameda County Health Care Services Agency, Oakland Unified School District, and Seneca Family of Agencies (2020, February–May); Blank, M. (2015). Building sustainable health and educational partnerships: Stories from local communities. The Journal of School Health, 85(11), 810–816; Center for Healthy Schools and Communities. (2020). Spotlight practice: Smart financing practices for school health centers. San Leandro, CA: Author; Center for Healthy Schools and Communities. (2020). Alameda County school-based behavioral health model. San Leandro, CA: Author; Detterman, R., Ventura, J., Rosenthal, L., & Berrick, K. (2019). Unconditional Education: Supporting Schools to Serve All Students. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. is California’s seventh-largest county and is home to 18 school districts. Several districts in the county are in varying stages of implementing community school initiatives. For example, Oakland Unified School District (Oakland Unified)—the largest district in the county, with an enrollment of over 50,000 students—launched its community school initiative in 2011.Information on the Oakland Unified initiative comes from the following sources: Interview with staff from Oakland Unified School District (2020, February 5); McLaughlin, M., Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2020). The Way We Do School. Cambridge; MA: Harvard Education Press; Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2015). Oakland Unified School District community schools: Understanding implementation efforts to support students, teachers, and families. Stanford, CA: John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities. The district currently operates as a full-service community school district—every school in Oakland Unified has adopted a community school model that incorporates the four pillars of the community school approach. To date, the district has formalized partnerships with more than 215 community-based organizations, which provide services such as academic supports, mentoring, after-school programming, and mental health services. Schools in Oakland Unified also benefit from 16 school-based health centers across the district that provide medical, optometry, mental health, health education, youth development, and dental services. In order to support school partnerships, Oakland Unified created a community school manager position, with just under half of Oakland Unified schools having this position on-site. Community school managers are typically part of schools’ shared governance teams, which also include administrators, students and families, school staff, and key community partners.

On the other end of the continuum, smaller districts such as Hayward Unified and New Haven Unified are in earlier stages of establishing community schools. Community school initiatives across Alameda County have benefited from partnerships with several county-level entities. In this section, we highlight two key organizations—Alameda County Health Care Services Agency and Seneca Family of Agencies (a nonprofit).

Alameda County Health Care Services Agency: Strategic Thought Partner and Service Provider

The Alameda County Health Care Services Agency (HCSA) oversees the county’s public health, environmental health, and behavioral health departments. Over nearly 25 years, HCSA has developed deep knowledge about how to build partnerships with schools and youth-serving agencies, such as Seneca Family of Agencies (described below). As a result, HCSA has been able to provide technical assistance not only in the form of direct services for community schools, but also as a thought partner for district leaders invested in developing community school initiatives. For example, HCSA partnered with Oakland Unified in a multiyear strategic planning process to develop Oakland Unified’s full-service community school initiative through a shared focus on the health and wellness of young people. Similarly, HCSA has worked closely with district officials in Hayward Unified and New Haven Unified to develop their community school initiatives.

The success of HCSA’s district partnerships is rooted in a shared understanding that community school initiatives and HCSA are mission-aligned and strategically interdependent; HCSA achieves better health outcomes by serving students and families through schools, and community schools are better able to access the resources and supports needed to optimize conditions for learning.

The Center for Healthy Schools and Communities (the Center), a department within HCSA, is the entity that manages HCSA’s technical assistance for community school initiatives, including the supervision of 28 school-based health centers throughout the county, the management and coordination of the School-Based Behavioral Health Initiative, and the staffing of district leadership positions that coordinate health and wellness supports. This technical assistance allows community schools in Alameda County to provide a wide range of integrated student supports.

The supports include:

- School-based health centers. Overseen by the Center, these school-based health centers provide essential support for community school initiatives and are an example of the partnership development needed to provide technical assistance to community school initiatives. For example, Oakland Unified benefits from a total of 16 school-based health centers that provide medical, behavioral, and dental health services as well as health education and youth development programming. This translates to essential services for students and families, such as medical and behavioral health screenings, reproductive health education, immunizations, prescription management, and dental care. These types of services allow schools to address student and family health issues preventatively, before those issues interfere with student learning.

- The School-Based Behavioral Health Initiative. The Center launched this initiative in 2009 in order to address the impact of trauma and behavioral health symptoms on students’ overall well-being and ability to engage in school. The initiative reaches more than 170 schools across all 18 districts in Alameda County (just over 40% of all schools in the county) and provides a range of services and programs, depending on district and school needs, including mental health consultation for school staff and parents; development of referral and service coordination systems; and the implementation of a COST approach, which help coordinate learning supports and resources. The COST strategy has been central to implementing full-service community schools in Oakland. In some cases, the School-Based Behavioral Health Initiative provides and funds school-based positions such as mental health clinicians. Like the school-based health centers, these types of services allow schools to address a range of student behavioral needs before they become a barrier to learning.

- District health and wellness leads. This role is designed to assess and develop the district’s health and wellness system, build the capacity of school staff, and manage partnerships with external health and wellness organizations. Currently, these leads are present in 14 of the 18 districts in Alameda County. Health and wellness leads are either employed by the Center or by districts themselves, depending on the availability of funding streams and the needs of the district. For example, Oakland Unified’s well-established community school initiative has secured funding to staff its own health and wellness lead. Other districts with newer community school initiatives have health and wellness leads supported by the Center. This is an example of how HCSA adapts its approach to technical assistance based on the status of the district community school initiative.

The technical assistance that HCSA provides to districts in the form of staffing, services, and coordination is supported by funding from a sophisticated tapestry of federal, state, and local dollars, as well as private philanthropic sources. For example, the Center provides an annual base allocation of approximately $120,000 to all 28 school-based health centers in Alameda County; this stable source of funding supports health center infrastructure and allows the health centers to provide services and programs that are not eligible for reimbursement by state or federal funding programs (e.g., Medi-Cal). The base allocation funding provided by the Center comes primarily from two sources: the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (a stable funding source that emerged in 2000, pursuant to litigation against four major tobacco companies) and Alameda County’s Measure A (a half-cent sales tax, in place since 2004, that supports medical services for low-income and uninsured county residents). Elected officials in Alameda County play a role as well by ensuring that steady funding for the Center is available year over year.

Now, a new partnership is emerging at the county level between HCSA and the Alameda County Office of Education (ACOE), with the two entities focusing their initial collaborative efforts on implementing services and supports for students experiencing homelessness. These partnering activities coincide with ACOE’s launch of a new social and emotional learning department, which will use the community school pillars and a whole child emphasis to frame the service and technology supports it provides to districts. Similar to HCSA staff, ACOE interviewees shared that coalescing around shared priorities—in this case, improving outcomes for students experiencing homelessness—can help interagency partnerships develop common goals and shared priorities, especially at the beginning stages, when partners may be entering the process with different language and directives.

Seneca Family of Agencies: Building Community Schools With a Strong Focus on Inclusion

Seneca Family of Agencies (Seneca) is a nonprofit that provides a coordinated continuum of care and services to students and families who have experienced trauma, with operations in Alameda County as well as in a number of other California counties and in Washington state. Through its Public School Partnership Program, Seneca partners with school districts and charter schools to provide high-need students—including students with disabilities, students engaged with the juvenile justice system, and students dealing with the effects of trauma—with school-based special education and mental health services.

Although Seneca does a great deal of work delivering mental health and special education services, the agency’s executive director describes this as a “foot in the door” that allows Seneca to facilitate a deeper redesign of school systems and practices, with the aim of creating schools that are built to serve all students well. Seneca frames its technical assistance around its model of MTSS, called Unconditional Education (UE), which pairs evidence-based academic, behavioral, and social-emotional interventions with a focus on school culture and climate. This model is anchored by a core principle: that an educational system can be designed to serve all students well only if the needs of its most vulnerable students are considered first. Along these lines, the agency aims to prevent the placement of students with disabilities into overly restrictive settings by providing technical assistance to help schools deliver in-classroom services, offer support and professional development to teachers to help them understand and manage student behavior, and implement evidence-based and trauma-informed practices. These strategies are in turn used to support the development of a positive school climate.

Seneca’s ability to engage in technical assistance that supports its school redesign work hinges on two key components: (1) its partnerships with other child-serving systems, and (2) its placement of UE coaches who are essentially community school coordinators at school sites. Seneca has found that implementing a continuum of community- and school-based services is difficult to accomplish with education funding alone. As a result, the agency partners with county mental health, social welfare, and juvenile justice systems to facilitate the coordination of resources and expertise that is required to comprehensively meet student needs. In particular, Seneca’s partnerships with county mental health agencies allow it to access state and federal funding through contracts under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment benefit (a federal entitlement to preventive health and mental health services for children enrolled in Medi-Cal) and California’s Mental Health Services Act. These funds support Seneca’s ability to develop tiered systems of supports at school sites, engage in broader school climate and culture work, deliver services to students and families, and provide professional development to teachers—all important technical assistance that is consistent with the integrated student support and collaborative leadership pillars of community schools.

Seneca’s UE coaches function like community school coordinators and work at a single school site for at least 3 years. The primary function of the UE coaches is to improve the internal capacity of each school by facilitating initial resource mapping; identifying funding streams; leading the COST; providing professional development to school practitioners; and facilitating 6- to 8-week cycles of intervention, in which collaborative school-based teams make data-informed decisions about intervention adjustments (e.g., moving students up or down a tier). Currently, Seneca’s partnership program serves 24 schools distributed across Alameda County, 5 of which have a full-time UE coach employed by Seneca. The other 19 partnerships receive direct services from Seneca, but without a UE coach.

Seneca also employs a number of other full-time on-site employees in addition to the UE coach, including clinicians, bachelor’s-level behavioral support specialists, special education teachers, school psychologists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists. Individuals in these latter positions are generally focused on providing direct services (i.e., they are not coordinative positions); work as full-time employees at specific sites (usually one site, although they may, rarely, be split between sites); and have their positions funded by multiple sources, including a school’s special education funding and county mental health funding.

What Does the Health Care Services Agency and Seneca’s Support Look Like in Action?

Hayward High, one of five high schools in the Hayward Unified School District, is a large community school serving over 1,700 students. Tiburcio Vasquez Health Center, an on-site health center, provides critical health services such as medical screenings, reproductive health counseling, and health education.Information in this section comes from an interview with staff from the Alameda County Health Care Services Agency (2020, May 13). The school also benefits from an on-site wellness center where students are able to receive drop-in counseling or referrals to off-site counseling through school partnerships with community organizations. Hayward High also offers after-school and summer programming through the district’s youth enrichment program, which includes academic tutoring, credit recovery, and driver’s education, among other offerings. Additionally, Hayward High provides opportunities for parent engagement, such as the school’s Parent Center and Parents’ Café, which are managed by the school’s family engagement specialist.

At the district level, HCSA funds a district health and wellness coordinator, who supported the development of Hayward High’s 25-person COST. Hayward High’s COST comprises a team of teachers, counselors, and administrators who work together to identify and track student needs and progress. The COST has now become a districtwide model that has spread to each of the district’s 30 schools.

HCSA has partnered with Seneca to provide critical resources and services to Hayward High students and families, and HCSA’s support has shifted to meet needs over time. Using Medi-Cal dollars, HCSA funds a full-time Seneca therapist and a part-time clinical intern who provide therapeutic interventions—including individual, group, and family therapy—to students needing intensive supports. Additionally, over the past 5 years HCSA has contracted with Seneca to provide staff to serve as Hayward High’s COST coordinator and part-time school wellness clinician and coordinator. These three positions are key to Seneca’s ability to provide a variety of services at the school, including mental health services to uninsured students, mental health consultations and professional development to school staff, consultations to administrators on school climate and culture initiatives, and parent workshops.

In June 2020, Hayward Unified received a federal Department of Education Full-Service Community Schools grant that will fund COST coordinators across all district schools. As a result, Seneca will slowly transition out of the role of supporting Hayward Unified’s COST. These shifts in support roles are typical of Seneca’s approach to working with schools and districts and allow it to adjust the level of support it provides as districts and schools develop their internal capacity.

District partnerships with HCSA and Seneca show how technical assistance for community school initiatives can come from both local government and nonprofit partners, and how county-level partnership development can bring resources—including services, funding, and staffing—to schools.

Lessons Learned

LACOE, Alameda County HCSA, and Seneca provide many forms of technical assistance for community school initiatives, including professional development and coaching; support for strategic planning; and establishing partnerships that bring direct staffing, services, and funding to districts and schools. These examples illustrate the important role that California county agencies and nonprofit partners can play in supporting district community school initiatives. By weaving together county-level services and resources to support a community school approach, these partnerships can leverage existing resources more efficiently and at scale and, in doing so, enhance the ability of schools to meet the urgent needs of students and families. Below, we present lessons learned from the efforts described in this brief.

Cross-sector partnerships at the county level can bring a comprehensive set of resources to local schools. Counties can coordinate partnerships across agencies and sectors, as well as leverage multiple funding streams effectively, by using a blending and braiding approach. Partners can include county agencies from different sectors, district and school leaders, and nonprofit organizations, each of which has a unique role to play and different resources to bring to the table. County partnerships can span a number of areas to meet the needs of children and families, including health care, social services, juvenile justice, and parks and recreation. By expanding beyond what is traditionally considered to be the educational domain, county-level partnerships allow districts and schools to offer a comprehensive, efficiently integrated range of services, supports, and opportunities for students. Coordinator positions at the county, district, or school level can help maximize the services in schools by leveraging funding from multiple sources and developing partnerships among local government agencies, school districts, and nonprofit organizations.

Cross-sector partnerships are strengthened by a shared vision and clear agreements among partners. Strong partnerships among key county agencies (including education, public health, mental health, and social services), districts, and nonprofit organizations require buy-in from leaders at the top of each organization and a clear commitment to a shared vision. This commitment can be spelled out in the form of a memorandum of understanding (as with the LA County pilot) or a letter that explains what each partner brings to the table, including funding, staff capacity, and service provision. By coalescing with partners around a shared cause (such as addressing homelessness in Alameda County) or goal (such as supporting the healthy development of children in Oakland Unified), county-level agencies can effectively support community school initiatives in districts. Strong partnerships are also flexible enough to evolve over time. One way that this can happen is for counties to include a needs and assets mapping process in the technical assistance they offer, as the LA County pilot did, and to subsequently provide tailored support to districts or schools based on that process, as in Alameda County, where district community school initiatives at differing stages of development receive different kinds of support.

A Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) and a Coordination of Services Team (COST) can help partners coordinate, deploy, and target their resources efficiently at school sites. Community school initiatives rely on structures that manage the process of referring students and delivering services at school sites. California has invested in an MTSS through an initiative led by the Orange County and Butte County Offices of Education.Orange County Department of Education. (n.d.). Guide to understanding CA MTSS (accessed 05/15/20). Because an MTSS is designed to provide layered tiers of services to students, ranging from preventive services for all students to more intensive and targeted interventions, it can align well with the coordination of community school programs and services. Both LACOE and Seneca directly incorporate MTSS into their community school initiatives. Similarly, establishing a COST at a school site puts a thorough and well-organized referral process into place to ensure that students receive the support they need. Alameda County HCSA worked closely with Oakland Unified to train community schools on the COST process in the early stages of the district’s full-service community school initiative. Counties can incorporate MTSS and COST into their technical assistance efforts, when appropriate, in order to strengthen the delivery of services at community school sites.

Conclusion

As the examples in this brief demonstrate, community schools offer an evidence-based approach to meeting the needs of students and families that present barriers to learning when they remain unaddressed. This approach is grounded in the four pillars of community schools: integrated student supports, expanded and enriched learning time, active family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership and practices. Counties can play an essential role in supporting community school initiatives in districts, because they are able to form cross-agency and cross-sector partnerships that leverage a variety of funding streams, resulting in well-integrated service delivery at community school sites. Counties can also provide technical assistance in the form of professional development and coaching, as well as strategic planning support. At a time when California families are under great stress due to COVID-19-related school closures and economic pressures, and the education and social service sectors face severe budget strains, it is more important than ever to find ways to build on existing services and partnerships to efficiently deliver well-coordinated academic, physical, mental, and social-emotional supports for students.

Leveraging Resources Through Community Schools: The Role of Technical Assistance by Anna Maier, Sarah Klevan, and Naomi Ondrasek is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.