New Mexico Community Schools: Improving Student Opportunities and Outcomes

Summary

This brief highlights lessons learned from New Mexico’s investment in community schools. Drawing on profiles of three sites that received state implementation grants, we find that community schools implementing the key practices at the center of New Mexico’s community schools framework are seeing improvement across a range of indicators, including growth in test scores, increased graduation rates, reduced chronic absence, increased student engagement and connectedness, improved school climate, greater access to mental and physical health care, and stronger family engagement. Key to achieving these outcomes were state investments to support hiring school coordinators and to provide professional development and technical assistance. These findings suggest ways that New Mexico can sustain this new model and improve implementation in the future.

Introduction

Since 2019, New Mexico has invested in community schools as an equity-centered, evidence-based approach to better serve the needs of students. The New Mexico Public Education Department (PED) defines community schools as “a whole child, comprehensive strategy to transform schools into places where educators, local community members, families, and students work together to strengthen conditions for student learning and healthy development.” Community schools achieve these goals by partnering with local organizations and families to organize in- and out-of-school resources and supports, such as physical and mental health services, meals, after-school programming, and other learning and career opportunities to address the specific needs of their communities.

Prior research finds that well-designed and fully implemented community schools are associated with a range of positive outcomes, including increased attendance rates; reductions in disciplinary incidents; improvements in students’ self-reported engagement, sense of connectedness to adults and peers, and attitudes toward school; and improvements in school climate and student achievement.Covelli, L., Engberg, J., & Opper, I. M. (2022). Leading indicators of long-term success in community schools: Evidence from New York City [EdWorking Paper 22-669]; Johnston, W., Engberg, J., Opper, I., Sontag-Padilla, L., & Xenakis, L. (2020). Illustrating the promise of community schools. RAND Corporation; Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools: An evidence-based school improvement strategy. Learning Policy Institute & National Education Policy Center. Since 2023, the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) has worked with New Mexico education partners, including the Southwest Institute for Transformational Community Schools and the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County (ABC) Community School Partnership, to conduct research on the implementation of New Mexico’s community school grants. Most recently, LPI published profiles documenting community school implementation in three districts across New Mexico—Albuquerque, Peñasco, and Roswell—each of which received state support through implementation grants.

This brief synthesizes the findings from these profiles, which drew on interviews, observations, and a review of relevant documents to illustrate how these community schools leveraged grant funding in service of student thriving and family well-being. These sites, in partnership with their district, community partners, and families, integrated the six key practices of community schools into the strategic vision and daily operation of the school, leading to improvement across a number of measures. The successes noted in the profiles demonstrate the promise of community schools, while struggles around sustainability and the desire for greater transformation point to new opportunities for the state to continue its innovative school transformation efforts.

History of New Mexico’s Investment in Community Schools

Community schools are not new in New Mexico. Their guiding principles date back to at least the 1930s, particularly in tribal communities. The Nambé, whose tribal land is in northern New Mexico, had a community school guided by the following principles:

A school should be the center of the community. It should be sensitive to the needs of the community, and in cooperation with parents, plan a program that will make the best use of all available resources. Such an environment should stimulate pupils to engage in many activities. Through participating in planning, executing, and evaluating their work, they will learn to think and learn the facts and tools of learning. They should find the school a vital place in which to live.As quoted in Tireman, L. S., & Watson, M. (1948). A community school in a Spanish-speaking village. University of New Mexico Press.

Community schools garnered renewed interest in New Mexico in the late 2000s, spurred by philanthropic investments from Atlantic Philanthropies and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. State support for community schooling began in 2013, when the legislature adopted the Community Schools Act, allowing any public school to become a community school and focusing on extended learning, school-based health care, family engagement, and other wrap-around services. The 2019 update introduced a community schools framework, added collaborative leadership to the key features of community schools, and identified culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and restorative approaches as essential.NMSA 1978, § 22-32 (2019); Oakes, J., & Espinoza, D. (2020). Community schools the New Mexico way. Learning Policy Institute. Most recently, PED adapted a national framework for fully implemented community schools. This new framework aligns with and builds on the Community Schools Act by including two additional key practices of implementation informed by the science of learning and development: rigorous, community-connected instruction and a culture of belonging, safety, and care.

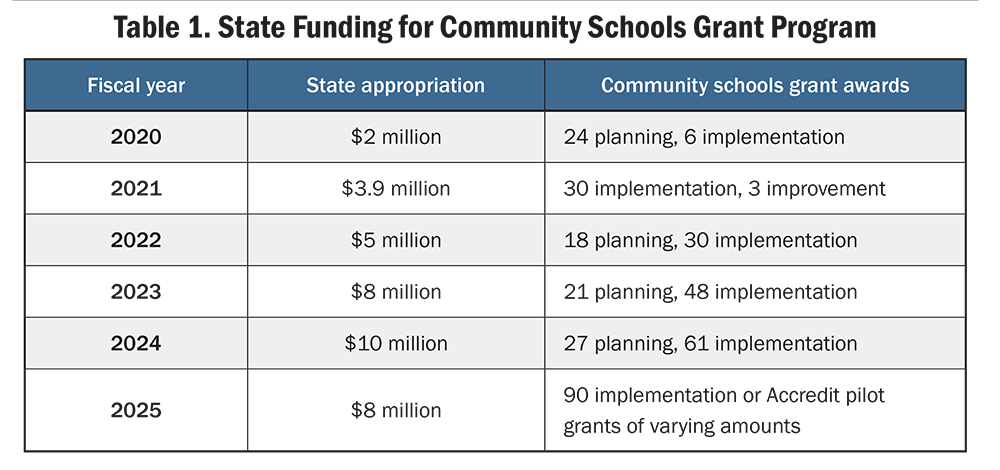

Legislative funding to help schools implement the strategy began in 2019 with an initial $2 million in grant funding. Since 2019, $36.9 million in community schools funding has been allocated to PED for grant funding, grant management, and technical assistance (see Table 1). The funds have allowed the strategy to spread across the state, enabling districts to secure a full-time community school coordinator at each school and pursue collaborative planning.

For the 2024–25 school year, 90 schools either received funding for implementation grants or were designated to participate in the Accredit Community Schools pilot program.In 2024, the legislature reduced the state appropriation from $10 million to $8 million, with 54% of that amount awarded as grant funding. Of the $8 million appropriated for grantmaking, PED awarded $4,340,000 in grants for 2024–25, which is approximately 54% of the total appropriation, plus an additional $1,367,605 in reverted (unspent) funding from 2023–24 grantees that PED redistributed across the grantee pool. The Accredit Community Schools pilot program was established for community schools that were aging out of their state grants (finishing their 4th year of implementation) or that had been operating for a long time and had a community school coordinator. Each school received up to $75,000 in grant money to continue with implementation and help cocreate a community schools certification process. The certification pilot has stalled, but the schools still received their grant awards in 2024–25. See the NMPED Community Schools Act Grant Applications Guidebook for 2024–25. The amount allotted to grantees was lower than in previous years, due to a $2 million reduction in the state appropriation for community school grants (from $10 million to $8 million). To help fill the gap, PED allocated unspent funding from the 2023–24 grants to the 2024–25 grantee pool. In another departure from the past, grant money was given to districts in a lump sum to disburse, instead of specifying amounts for individual schools. An additional $59 million in state funding was appropriated to the State Equalization Grant (SEG) for “educational innovations” such as teacher mentorship, educational planning, literacy and career and technical education programming, and community schools. While there was no requirement that districts use the SEG funding for community schools, PED issued guidance that “strongly encourage[d] schools to prioritize funding for a community school coordinator position” using this funding. Despite these efforts by PED, the funding cuts had a destabilizing effect on many community schools, including those profiled in this brief.

New Mexico’s state support, coupled with its unique state-level collaborative governance style, has created productive foundations for community schools. The New Mexico Coalition for Community Schools, a multisector state body established by the 2019 legislation, collaborates with PED to provide advocacy, capacity-building, and technical assistance.H.B. 589. 54th Leg., 1st Reg. Sess. (NM. 2019). The legislature passed House Memorial 44 in 2023, creating a task force to study sustainable funding—including the use of certification models—and develop a strategic plan for community schools.

Finally, New Mexico has benefited from federal support. In 2022, Albuquerque, Las Cruces, and Taos received Full-Service Community Schools grants, with total expected funding of $7.5 million, from the U.S. Department of Education to implement and operate community schools. The U.S. Department of Education has also provided federal funding through a congressionally directed spending award of $1.8 million to provide technical assistance and build the capacity of New Mexico community schools.This is the funding received by ABC Community School Partnership, Communities in Schools of New Mexico, and National Education Association–New Mexico to support community schools implementation in the state, part of which is supporting the Learning Policy Institute’s research. These investments in community schools across the state are positively impacting students and families.

Case Study Sites

Sites were selected based on demographic and geographic diversity as well as evidence of improved outcomes of student well-being and achievement. Links to individual case study briefs for each site may be found at the beginning of each description below.

Los Padillas Elementary School sits at the southernmost border of Albuquerque Public Schools (APS) and serves about 200 students. The neighboring area is surrounded by farmland and has a rural ambiance, despite being located in the biggest city in New Mexico. APS is deeply committed to the community schools strategy, with just over 40% of the district’s 68,000 students attending community schools, all of which are supported by a unique multi-institutional partnership, the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County (ABC) Community School Partnership. In 2018, Los Padillas adopted the community schools strategy in response to its More Rigorous Intervention (MRI) designation as a result of several consecutive years of low test scores. Subsequently, the school underwent a remarkable transformation driven by a shared vision grounded in authentic community and family engagement, leading to marked improvements in reading and math achievement and a 50% reduction in the rate of chronic absence between 2021 and 2024. Los Padillas’s community schools strategy, bolstered by a PED community schools implementation grant, centers on culturally relevant, sustaining, and community-connected learning opportunities, including dual language instruction, outdoor education, and student-elected enrichment activities.

Peñasco Independent School District, in Taos County in northern New Mexico, is a rural community school district serving approximately 280 students across two schools: Peñasco Elementary and Peñasco High. Approximately 10% of students, many of whom live in the Picuris Pueblo located nearby, identify as Native American. Community schools implementation began in 2021–22, when the elementary school received a first-year implementation grant from PED and the high school received a planning grant. In the following years, the high school graduation rate increased to over 90%, compared to 76% statewide, and the elementary school’s K–2 students were outpacing their state peers on formative reading and math assessments. Peñasco’s approach to community schooling focuses on culturally relevant, community-connected learning (including project-based learning and career and technical education), family and community engagement, and support for students’ health and wellness. The district engaged students, families, staff, and community members in a deeply collaborative strategic planning process that led to a compelling purpose statement, graduate profile, and strategic plan that continue to guide the work.

Roswell Independent School District (RISD), in southeastern New Mexico, is a small urban district serving about 10,000 students across 21 schools. RISD has four community schools, including Sierra Middle School, entering its fifth year of implementation, and University High School, an alternative school entering its third year of implementation, both supported by PED implementation grants. Both Sierra and University High have drawn on the community schools strategy to create a nourishing school climate and culture and promote student well-being. As a result, at University High suspensions dropped from 274 to 61 in 2024, and the graduation rate increased by nearly 20 percentage points. In addition, substance abuse infractions dropped by 80% at both schools. These outcomes are driven by Roswell’s focus on providing culturally responsive and restorative spaces focused on relationship-building and strong communication with parents and family members, expanding opportunities for student voice and engagement through an elected student senate at University High and student-led after-school programming at Sierra, and stitching together a social safety net to address out-of-school learning barriers.

Progress in New Mexico Community Schools

Each of the community schools we profiled has achieved tangible successes that underscore the benefits of the strategy. Staff in these community schools emphasized improving engagement, reinvigorating school climate, and addressing out-of-school barriers to learning as levers that complement a shift to more rigorous and culturally sustaining teaching and learning. As a result of this work, the schools have seen improved climate indicators and positive impacts on student and family well-being paired with successes in outcomes like decreased chronic absence and increased academic achievement. The profiles provide detailed findings across a range of measures, including:

-

positive trends in school climate data, including rising percentages of students reporting having a caring adult in their life, feeling a sense of belonging, and liking school;

-

better access to mental and physical health services, including through school-based health centers;

-

growing family engagement through volunteering, participation in community school councils, and increased attendance at school events;

-

improved student engagement through choice in after-school programming and avenues for student voice;

-

high teacher retention rates;

-

significantly reduced chronic absence rates in two of the three sites since 2022;

-

big declines in, or maintaining a low rate in, the number of suspensions;

-

rising and high graduation rates in high schools;

-

growth in reading and math test scores among 3rd- to 5th-graders; and

-

increasing numbers of K–2 students classified as on grade level via state-required formative assessment.

These schools have made much progress, but they believe that more can be achieved. They approach this work with confidence, noting that the improved outcomes associated with becoming a community school signal that they are on the right track.

Key Practices in New Mexico Community Schools

Within its community schools framework, PED has identified six key site-level practices that are grounded in research and the expertise of community school practitioners participating in the national Community Schools Forward task force. These are: (1) collaborative leadership, shared power, and voice; (2) powerful student and family engagement; (3) rigorous, community-connected classroom instruction; (4) expanded, culturally enriched learning opportunities; (5) a culture of belonging, safety, and care; and (6) integrated systems of support. As illustrated in the examples below, the integrated implementation of these key practices, tailored to the local school community, strengthens learning conditions for students.

Collaborative Leadership, Shared Power, and Voice

Across the profiled school districts, collaborative leadership was a bedrock of the work, feeding priorities for, and implementation of, the other key practices. School and district officials sought opportunities to bring the community in and design the school transformation process around what students, families, and community members said were their greatest assets and their most urgent needs. In rural Peñasco, district leaders leveraged close community ties to develop deeply collaborative foundational documents in which caregivers, community members, and students all had a voice. Emphasis on “community-integrated education through parent engagement and community activities” has since served as a North Star for the work in Peñasco. Similarly, at Los Padillas, collaborative leadership involved school and district leadership bringing families and the surrounding community into the center of the school redesign process after being designated as an MRI campus. The priorities established—bilingual education, family engagement, and outdoor learning—continue to drive implementation 5 years later.

Shared power in these community schools extends beyond convening community members to establish initial goals and priorities. Los Padillas’s community school council (also known as a site-based leadership team) meaningfully involves families and community partners, providing “the chance to do important things, not just cooking food or cleaning up the campus,” as one parent noted. Council members are actively involved in root cause analysis, setting goals, enacting interventions, and assessing those interventions. For example, the council was able to tie low levels of student motivation to a dearth of knowledge about future careers. As a result, parents worked with school leadership to restructure the annual career fair to inspire students to dream. They invited locals representing a range of occupations to set up displays and gave students ample time to walk around, touch job-related objects, and ask lots of questions.

Peñasco school and district staff listened to the insights and wisdom of students to inform their approach to school transformation. As part of a high school leadership course taught by the school’s community school coordinator, students surveyed their peers and teachers and developed recommendations on issues such as attendance, late work, and referral policies. After the proposals were presented to a receptive district and school staff, a district leader noted, “[This student input] was so impactful that we’ve asked ... that these meetings happen more often throughout the year. This way we get a better feel for how students are feeling ... and what kind of supports they need from us.”

Access to professional development and technical assistance allowed these sites to deepen their collaborative leadership practices. For example, Peñasco and Roswell participated in the Southwest Institute for Transformational Community Schools Principal Fellowship program, University High and Sierra in Roswell and Los Padillas in APS received district coaching, and the Los Padillas community school coordinator had access to weekly coaching and a professional network through the ABC Community School Partnership. In these community schools, collaborative leadership was simultaneously a starting point and an ongoing practice. Across the interviews and site visits, it was also clear that the priority placed on collaboration invigorated student and family engagement.

Powerful Student and Family Engagement

In the schools we studied, becoming a community school meant (re)establishing the school as a hub where caregivers, volunteers, and partners felt welcome. As a simple example, for multiple years, Sierra Middle in Roswell did not have a person in the front office who spoke Spanish. This was an impediment to serving many of their families because the vast majority identify as Hispanic, and many speak Spanish at home. Now, however, the school’s community school coordinator is a native Spanish speaker who can regularly be seen greeting families in Spanish or texting with caregivers to check in, offer support where appropriate, and, beyond all else, let members of the school community know they are welcome.

Profiled sites also demonstrated that once a school becomes a welcoming space, families engage more deeply in a variety of ways. Through the community school transformation process, Los Padillas became a welcoming site with robust family and community engagement. Over 2 days during the last week of the 2023–24 school year, more than 80 caregivers and community members spent time on campus. Some were core members of the active Parent Teacher Club, who were organizing and decorating for the upcoming 5th-grade promotion ceremony. Others volunteered for the bimonthly drive-up food bank, which was open to the entire surrounding community. More than 70 caregivers and community members showed up for the Genius Hour showcase of student accomplishments (see Expanded, Culturally Enriched Learning Opportunities). In Peñasco, due to intentional work by the community school coordinators to rebuild trust and find multiple avenues for communication with families, attendance at events like literacy nights and project-based learning showcases skyrocketed. During the 2023–24 school year, a winter light parade with about 20 floats, sponsored by local businesses, attracted nearly 500 people to the school. As one coordinator shared, it was a true community partnership effort. That was something Peñasco schools had not seen for some time.

Increasing student voice is another key strategy these schools used to improve engagement and student buy-in. Some sites, like Los Padillas and Sierra, gave students choice in developing after-school clubs and deciding which ones they would participate in. At University High, an elected group of students served on the newly established student senate. They took the responsibility of representing their fellow students and partaking in school decision-making very seriously. In their first year, the student senate established and oversaw weekly school announcements, rectifying a knowledge gap among students about upcoming events and other important happenings at the school. The students also recognized that many of their peers struggled to access hygiene and health products. Working with the community school coordinator to secure funds and board approval, they created Worry Walls, a collection of health and hygiene products available in the school bathrooms.

In addition to bringing more student and family voices into the school and offering services and opportunities to bring more families to campus, schools helped students connect with their local community and culture through their learning.

Rigorous, Community-Connected Classroom Instruction

All the study sites sought to more closely connect the classroom with the broader community in which students live. In Peñasco, project-based learning is a districtwide strategy for delivering more dynamic, grounded learning opportunities. In the 2023–24 school year, all teachers offered at least one project per semester. In one class, a watershed project took students to the top of a nearby mountain to study the source of Peñasco’s water. They analyzed water purity and the history of local water rights, ultimately creating a video titled The Fight for Water. Peñasco also taps community experts to teach a range of career and technical education courses featuring techniques grounded in local cultural traditions. The culinary arts program, complete with a new state-of-the-art kitchen, was led by a renowned local chef who helped students use the traditional horno (oven) to prepare chicos, slow-roasted sweet corn kernels, for the winter festival.

At Los Padillas, a focal point of community-connected instruction was the 5-acre wildlife sanctuary on the school’s campus. Once in disrepair and out of use, the space was revived as part of the school’s turnaround strategy. In the 2023–24 school year, 4th-graders embarked on a project-based unit to learn how to take care of the pond, which was overgrown with cattails. Students conducted research by going to different ponds in town and learning from experts how to clean water, clear cattails responsibly, and maintain the pond ecosystem. The sanctuary is also used as a place for storytelling. Tree stumps in a small clearing were fashioned into seats where students can listen to tribal leaders from around the state tell stories and share Native culture and history. Adopting a dual language curriculum, a community priority elevated as Los Padillas planned for implementation, is another way the school honors and elevates the language and culture of the surrounding community. Offering Spanish enabled stronger intergenerational connections as students learned the primary language of their grandparents; as part of this initiative, all staff on campus are encouraged to communicate in both languages. Through the community schools strategy, students were afforded a variety of classroom opportunities to be engaged in rigorous, community-connected learning.

Expanded, Culturally Enriched Learning Opportunities

Each of the school communities we visited was also committed to offering culturally enriched learning opportunities outside of the school day. These activities emphasized opportunities grounded in student interests, fun, and students’ culture. For example, the Genius Hour offered at Los Padillas Elementary in Albuquerque was devised as part of the school redesign and directly tied to community priorities around student voice, academic enrichment, and relationship-building. Students select an extracurricular activity (e.g., coding, robots, knitting, martial arts, mariachi) to focus on for 6 weeks, and they practice the skill daily in mixed-age groups with a teacher or local community partner. At the end of every 6 weeks, parents and caregivers are invited to the Genius Hour showcase to observe everything the students have learned, built, or produced. These events are well attended and offer a chance for families to have positive, informal interactions with teachers, further strengthening relationships across the school.

Sierra Middle in Roswell took a similar approach to after-school activities. Amid high levels of chronic absenteeism and declining student engagement following the COVID-19 pandemic, school staff were seeking ways to more actively involve students in decision-making around their education. One response was to allow students to select all after-school clubs. The shift was met with enthusiasm from the students. One administrator shared, “This was a big thing for them. They feel like they’re valued. They feel like, ‘Oh, my opinion matters!’” The process is truly student-led. Students brainstorm club ideas, collect names of interested peers, and seek teachers to host the clubs with sufficient interest—teachers are compensated for the additional hours through community schools grant funding. If a teacher signs on, students seek approval for the new club from the community school coordinator and principal. The most popular club on campus is Anime Club; however, Earth Club, Lego Club, Harry Potter Club, and Young Birders Club all have passionate followings as well.

By creating a welcoming space for students to express more of themselves and connect with peers around shared interests, these community schools are actively fostering relationships across grade levels and building a positive culture in their buildings. In the following section, we explore additional steps the schools took to increase students’ sense of belonging.

A Culture of Belonging, Safety, and Care

In their distinct ways, each of the profiled schools sought to make the school a welcoming, warm, and safe place for students and a hub for the school community. Each school implemented a range of structures, practices, and policies related to climate and culture that prioritized trust-building, authentic relationships, and social-emotional well-being.

Across sites, educators gravitated to the adoption of restorative practices as an important strategy for improving school climate. At Sierra, for instance, teachers felt that by gaining skills in restorative justice, they could equip students to better resolve conflicts themselves and, ultimately, maintain healthier relationships. As one Sierra school administrator noted, “A lot of times we don’t give kids credit for being able to solve problems, and teachers want to take over and just [say], ‘OK, this is what we’re doing.’” Focusing on relationship-building and conflict resolution was informed by data gathered in Sierra’s initial needs and assets assessment, in which only 4% of students reported having a caring adult in their life, and school administrators noted bullying was contributing to students feeling unsafe. As a result, Sierra identified school climate as a priority area and viewed the community schools strategy as an opportunity to develop nurturing relationships with students

Educators in Peñasco attended to students’ social-emotional wellness by establishing a Wellness Room for high school students. The Wellness Room is staffed by a longtime Peñasco resident who is the former Spanish teacher, the current cross-country coach, and a retired Marine and firefighter. A colleague noted that “he has established a lot of trust with students and parents. That’s key, especially in a rural community.” The Wellness Room is a peaceful space with strands of twinkling lights, thriving green plants, statues of panthers (the school mascot), a circular table, and comfortable chairs. Students can self-refer to this space for conflict mediation or if they simply feel hungry, tired, or overwhelmed. The Wellness Room also serves as a restorative space that offers a nonpunitive alternative to disciplinary issues and a replacement for out-of-school suspension. Students with disciplinary issues come to this room to receive support, do classwork, and prepare to return to class.

The community schools we visited were sites where adults are deeply engaged in developing authentic relationships with students. At their heart, each of the practices researchers observed were grounded in trusting students and inviting them into the process of building a more welcoming and nurturing school environment.

Integrated Systems of Support

Across the community schools profiled, there was a recognition that what happens inside the school building is intimately connected to what happens outside of it. This was most visible in the way that community schools sought to stitch together a stronger social safety net for students and families. For example, Sierra used initial community school funding to construct a professional-grade health clinic on campus to fill a need for timely access to health care, a problem that even existed for one of the school leaders in the district:

I haven’t been able to get in to [see] a doctor for over 6 months. ... I can’t imagine what my parents [at my school] are going through with [their] kids, because I know what hoops to jump through, and a lot of our parents aren’t able to traverse those hoops.

Peñasco Independent School District also cohosts a school-based health clinic with a local partner. The center is open 2 days each week and provides vaccinations, physicals for athletic requirements, and counseling. One educator noted, “For some of our kids, it’s the only health care they ever receive.” Los Padillas is geographically isolated from physical and mental health facilities. The staff there are committed to securing funding for a school-based health center or mobile clinic and bringing more mental health resources to the school during the 2024–25 school year.

Outside of the school-based clinics, partnerships with a range of medical providers (e.g., dental, vision, and mental health) also increased student and family access to services. In Peñasco, Taos Behavioral Health provides push-in classroom support to approximately 15% of students experiencing severe emotional distress, a service billed to Medicaid. Families and students at Sierra Middle identified a need for increased access to therapy. Outside of school, a crisis appointment might be feasible within 4–6 hours, but a student may have to wait up to 2–3 months for any kind of follow-up. In response, the district hired a school-based therapist who rotates to various schools to provide therapy, including group therapy, which allows schools to increase the number of students they can serve. Unfortunately, due to budget cuts during the 2024–25 school year, Sierra could no longer afford this highly valuable therapist. Educators are searching for alternative funding to rehire the therapist.

Community school coordinators developed and leveraged other types of partnerships to meet several non-health-related student and family needs. With the support of partners, each of the schools we visited housed clothing and supply closets and operated food distributions. At Los Padillas, where many students are being raised by grandparents, the school developed a partnership with the University of New Mexico to offer legal services to grandparent caregivers who did not have legal guardianship. They helped grandparents understand their rights and how to access services and benefits for the students. La Casa Behavioral Health, a community-based organization that leads a substance abuse group for students, partnered with both Sierra and University High in their campaign to tackle a vaping problem on their campuses. The community schools strategy enabled coordinators to leverage supports and partnerships to meet student and family needs, both basic and complex.

Future Opportunities

New Mexico established its community schools grant program in 2019 and continued to invest in it for the next 6 years. The resources served as seed money for planning and implementation and provided consistent funding for the salary of a community school coordinator. As the three profiled sites demonstrate, this investment is paying off with progress at the school and district levels. A combination of strong local leaders who benefited from technical assistance and professional development in collaborative leadership; intentional engagement and relationship-building among students, families, educators, and community partners; and partners providing services and opportunities to reinforce the implementation of the key practices helped lead to these results.

The state is now at a pivotal moment for its community schools investment. The recent reduction in grant funding has had a destabilizing impact on local implementation, such as reduced services for children, eliminated positions, and constrained programming. For example, Peñasco lost one of two community school coordinator positions, with the remaining coordinator now responsible for both the elementary and secondary school. Roswell experienced reductions in its overall budget for community schools–related work, leading to reductions in mental health therapy for students, data entry support for community school coordinators, and funding for teachers to provide after-school instruction. Los Padillas did not experience cuts to the same extent, largely due to the support of the ABC Community School Partnership network. At the same time, the PED-convened House Memorial 44 Task Force has fulfilled its purpose and developed a set of recommendations for sustainable, recurring funding for community schools and a certification process to promote effective implementation, among other things.

New Mexico now has the opportunity to build on the successes of its investments in community schools. One key step is to provide a sustainable, long-term, dedicated funding stream for the coordinator position. Some states, including Maryland and New York, accomplish this by putting an allocation for this type of staffing into the formula for all high-poverty schools. Funding this position, which is central to community schools implementation, allows schools to more effectively and efficiently develop partnerships that enable blending and braiding of additional resources and bring in services and opportunities that match the local needs and goals of the school community. The returns on this type of investment can be substantial, as evidenced in the cases above. In addition, the profiled sites had access to technical assistance and professional development offered by districts, local partners, and nonprofits. Greater access to such implementation support for all community schools could further improve community school success. Policymakers can help develop and provide resources for a stronger system of technical assistance and capacity-building efforts that lead to fidelity of practice.

When community schools have the resources to implement the strategy effectively, they can change the lives of students and families. The profiled schools are seeing improved outcomes in high-impact areas like school climate, attendance, test scores, and graduation rates. Ensuring the sustainability and stability of this strategy will serve to strengthen the capacity of community schools to continue to achieve outcomes and improve equity and opportunity for young people across the state. If state leaders can maintain a stable investment in funding to seed, expand, and sustain the strategy and provide technical assistance and capacity-building (while allowing for local flexibility), New Mexico can build an ecosystem of well-implemented and strongly supported community schools.

New Mexico Community Schools: Improving Student Opportunities and Outcomes (brief) by Emily Germain, Anna Maier, and Daniel Espinoza is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work was supported by the ABC Community School Partnership. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.