Instructionally Engaged Leaders in Positive Outlier Districts

Summary

This brief summarizes the practices of successful, instructionally engaged leaders and the ways districts develop these leaders. These practices are drawn from “positive outlier” districts in California that have excelled at helping African American, Latino/a, and White students achieve at high levels on assessments of academic standards in English language arts and mathematics. Case studies of seven of these districts indicate that districts can develop leaders by identifying leadership talent from among teachers and then cultivating their talent to enable some to move into principalships and central office positions. Successful practices of these leaders included engagement in collaborative professional learning through observation of instruction, participation in professional learning communities, and use of student data to guide school and district decisions.

The full report on which this brief is based is available here.

District and school leaders play an important role in supporting teachers and contributing to student success. Research studies associate increased principal quality (e.g., ability to set a vision, develop people, and manage change) with gains in high school graduation ratesCoelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109; Leithwood, K. (2010). Characteristics of school districts that are exceptionally effective in closing the achievement gap. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 245–291. and student achievement.Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals [NBER Working Paper w17803]. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Leithwood, K. (2010). Characteristics of school districts that are exceptionally effective in closing the achievement gap. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 245–291. Superintendents’ longevity in the office is also generally associated with improved student achievement.Myers, S. (2011). Superintendent length of tenure and student achievement. Administrative Issues Journal: Education, Practice, and Research, 1(2), 43–53; Plotts, T., & Gutmore, D. (2014). The superintendent’s influence on student achievement. AASA Journal of Scholarship & Practice, 11(1), 26–37; Waters, J. T., & Marzano, R. J. (2007). School district leadership that works: The effect of superintendent leadership on student achievement. Education Research Service Spectrum, 25(2), 1–12.

Recognizing the importance of educational leaders, districts are paying more attention to how they develop their leaders, including how to grow effective leaders who focus on instruction that promotes equitable access to learning.Leithwood, K. (2010). Characteristics of school districts that are exceptionally effective in closing the achievement gap. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 245–291. How can districts develop strong leaders and what do these leaders do?

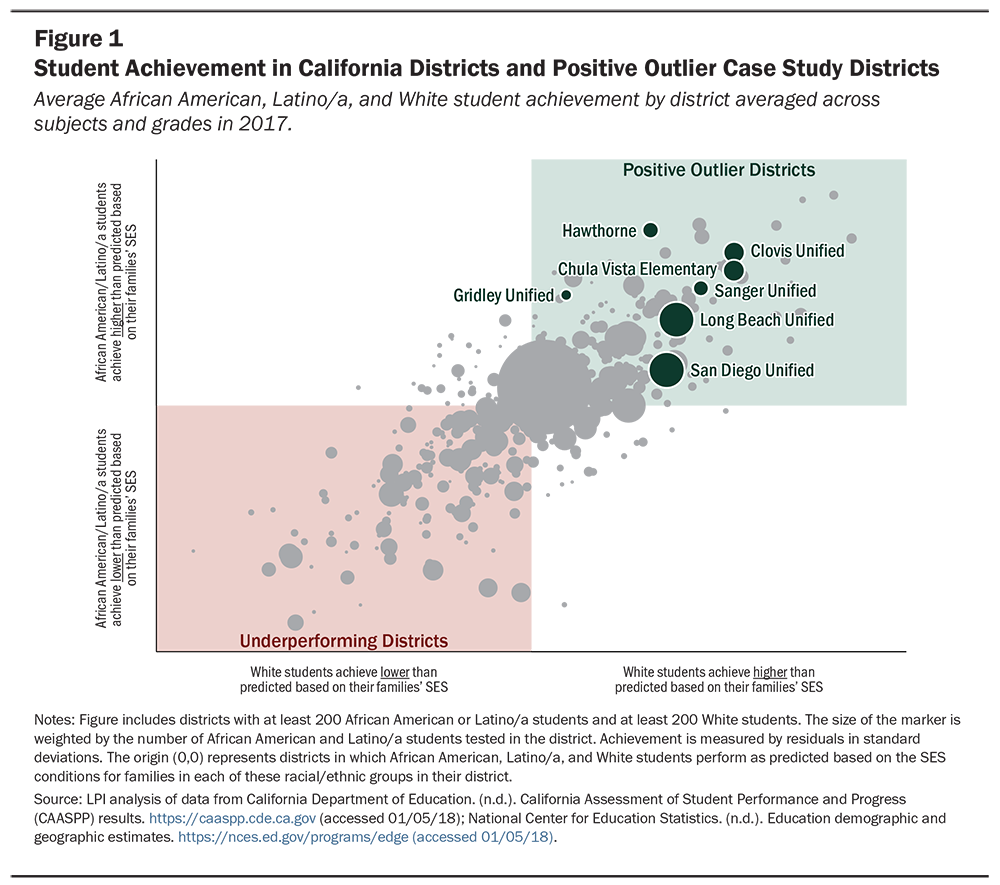

These questions were addressed as part of a series of Learning Policy Institute studies. First, researchers identified “positive outlier districts” in California in which—accounting for differences in socioeconomic status (SES)—African American, Latino/a, and White students substantially outperformed their peers on California’s state assessments.The measures of district performance are the residual scores produced by a statistical model that assessed the difference between districts’ predicted California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress English language arts and math scores and their actual average scores in 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17 for African American, Latino/a, and White students. Districts in the top right quadrant of Figure 1 were identified as positive outlier districts because African American and Latino/a students, as well as White students, excelled in both mathematics and English language arts.

The researchers then conducted individual case studies, including extensive interviews and reviews of administrative data, in seven of the positive outlier districts, selected for their geographic and demographic diversity. (See “The Positive Outlier Case Study Districts” for descriptions.) The goal was to understand more deeply the factors that may account for the success of their students, in particular their students of color. Successful leadership practices are especially important to examine given the role strong and stable leadership can play in schools’ success, especially for those serving diverse student populations.Levin, S., & Bradley, K. (2019). Understanding and addressing principal turnover: A review of the research. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. This brief describes insights from an analysis of all seven district case studies related to the school and district leadership.

These districts employed a variety of strategies for developing leaders who would stay in the district long term and for engaging leaders in districtwide professional learning through observation of instruction, participation in learning communities, and the use of data. This type of leadership was essential to implementing new Common Core State Standards, which shifted instruction to more meaningful learning for all students. This move to deeper learning necessitated leadership focused on instruction throughout schools and districts. This brief summarizes the districts’ strategies and concludes with lessons learned and guidance for policymakers.

The Positive Outlier Case Study Districts

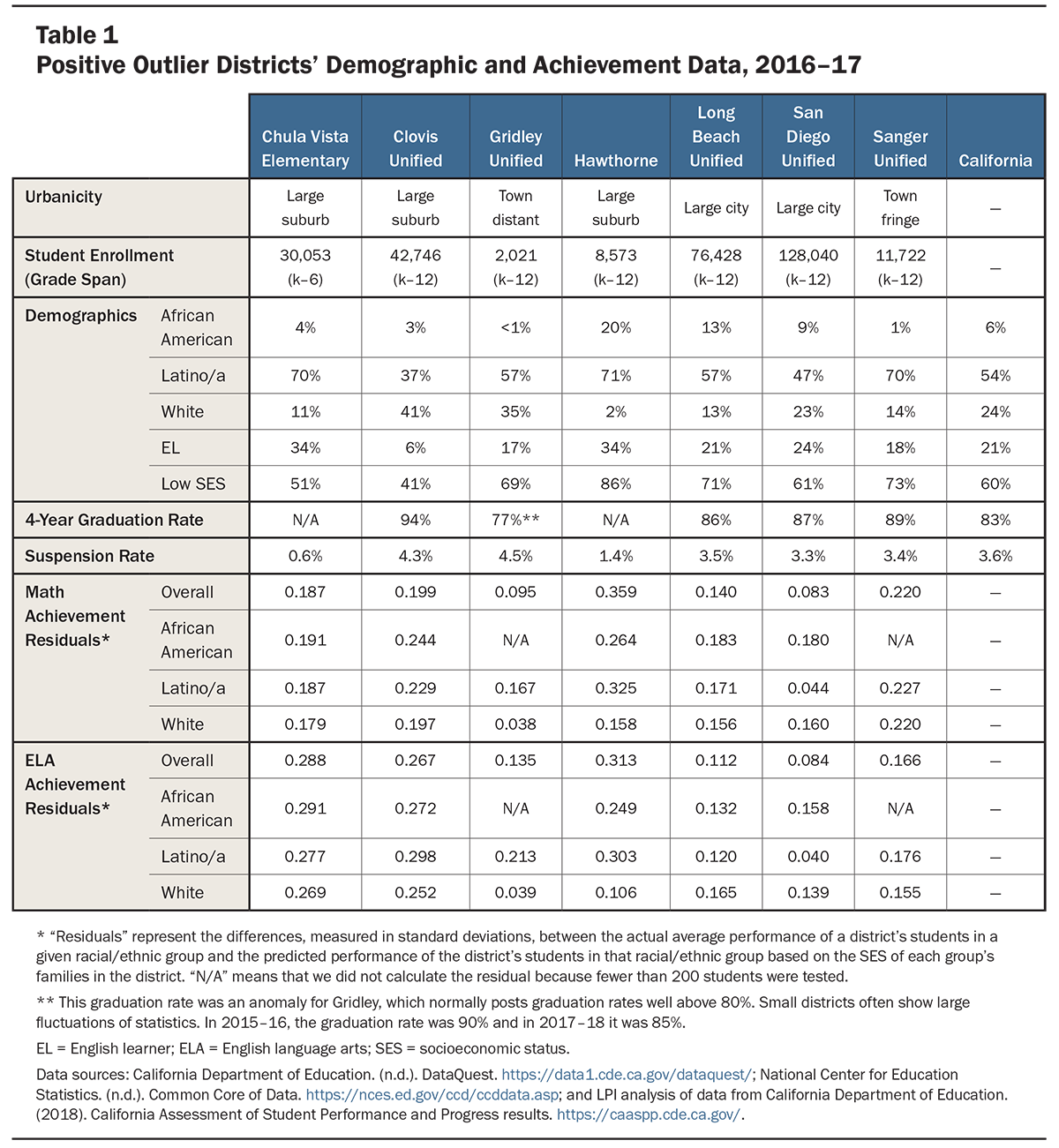

This brief summarizes lessons learned from case studies conducted at seven “positive outlier” school districts in California.Burns, D., Darling-Hammond, L., & Scott, C. (with Allbright, T., Carver-Thomas, D., Daramola, E. J., David, J. L., Hernández, L. E., Kennedy, K. E., Marsh, J. A., Moore, C. A., Podolsky, A., Shields, P. M., & Talbert, J. E.). (2019). Closing the opportunity gap: How positive outlier districts in California are pursuing equitable access to deeper learning. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Table 1 provides more information about these districts.

As Table 1 shows, the districts typically have higher-than-average percentages of English learners and/or students from low-income families but outperform other California districts serving students with similar socioeconomic status (SES). Achievement levels are shown as “residual” scores, which express the difference between students’ actual scores and the average performance of similar students in other districts. Any number above zero is a positive difference. Residuals near 0.2 or above are exceptional.

Committed and Experienced Leaders

Continuous, stable district leadership was a key factor in positive outlier case study districts, and one that educators frequently identified as contributing to students’ successes. The districts generally had sustained leadership from their superintendents and from many principals. The districts also intentionally recruited leaders from within. This created a leadership pipeline in which teachers who were strong leaders took on more and more responsibility for school leadership, and some eventually became principals. Principals, in turn, could expand their leadership roles and become district administrators.

Stability and Longevity

In all the districts, superintendents had multiple years of experience in their positions and had often come up through the ranks as principals, assistant principals, and teachers. For example, in San Diego, Superintendent Cindy Marten, who assumed the leadership role in 2013, was a teacher and principal in the district before reaching the central office. Similarly, in Long Beach, Superintendent Chris Steinhauser served in the role for 18 years before announcing his retirement in 2019, having previously been a student, teacher, principal, and associate superintendent in the same district. He was replaced by his deputy superintendent, Jill Baker, who has been in Long Beach Unified for nearly 28 years as a teacher, principal, and central office administrator. Multiple district and school staff members emphasized the importance of their superintendents’ long tenures in the district, especially given the generally short tenure of many urban superintendents.Council of Great City Schools. (2014, Fall). Urban school superintendents: Characteristics, tenure, and salary. Eighth survey and report. Urban Indicator, 1–10. (accessed 07/20/20).

In Clovis, Superintendent Eimear O’Farrell, appointed in 2017, began in the district as a teacher in 1993 and climbed through the ranks, as did her predecessor, Janet Young, and the founding Superintendent, “Doc” Buchanan. Typically, school principals have been Clovis teachers, area superintendents were former principals, and senior district office administrators were former area superintendents. District administrators were thus steeped in the culture of the district and were highly regarded as educators by teachers.

Similarly in Hawthorne, the District Superintendent, Helen Morgan, had been in the position since 2010, having previously worked as a coordinator for professional development; a principal; and a teacher, including 6 years as president of the teachers association. Her colleagues said this longevity and breadth of experience gave her a big-picture perspective on the district. As in all the districts, the longevity of leaders in Hawthorne contributed to stability and trust. Teachers and district leaders noted how this generated a sense of participation in a collective enterprise and common purpose. A Hawthorne school board member explained that this contributed to a positive climate in the district:

A lot of our administrators have come up through the ranks, where they were teachers at first and eventually [got] their credentials and move[d] on.… Even [the] superintendent, you know, she was a teacher at one point. I think there’s a certain appreciation for everybody’s role. We don’t have a sense of hierarchy.

Of our case study districts, rural Gridley was the only one with a superintendent who had come from outside the district relatively recently. However, the district had substantial periods of stability in the position of superintendent itself. The present Superintendent, Jordan Reeves, was appointed in 2016 following 4- and 8-year tenures, respectively, of his two predecessors.

Leadership Pathways

These districts did not just get lucky with their leaders. Instead, they cultivated leadership and created pathways to school leadership, the principalship, and the central office.

To cultivate leadership, districts involved staff in leadership activities and professional learning at all levels of the system, building trusting relationships and distributing responsibility and ownership. Professional learning, including mentoring and coaching, was collaborative, ongoing, and coordinated across the system. Teachers had many opportunities to take on leadership roles as they were encouraged to share their expertise. In these ways, district-level leadership was typically augmented by school-level and classroom-level leadership, developing a pipeline of strong leaders at each level.

By involving multiple staff members in leadership, districts got to know their school and teacher leaders, offered mentoring and coaching, and created pathways to greater leadership responsibility. For example, in Chula Vista, Francisco Escobedo, the Superintendent since 2010, explained that the most successful school principals were tapped to apply for senior leadership roles. Promotion of effective and experienced principals from within Chula Vista’s ranks further fostered stability across the district and allowed those deeply familiar with the district to inform ongoing leadership development.

Similarly, Sanger’s Superintendent, Adela Madrigal Jones—who worked in Sanger for more than 30 years as a teacher, principal, and associate superintendent—emphasized the importance of cultivating a teacher pipeline into leadership positions. The district offered teachers frequent opportunities for professional learning and mentorship, so that they could progress from leadership of professional learning communities, to curriculum support providers (who coach and support classroom teachers), to assistant principals or principals, and later to district specialists or administrators.

This strong leadership pipeline helped ensure continuity of principles and practices within the district. It also meant that Sanger had a “deep bench” for leadership, so that principals moving into district leadership did not significantly deplete a school’s leadership capacity.

Instructional Leadership

In positive outlier case study districts, leaders with deep experience in their districts focused on instructional changes. These leaders, who had frequently been teacher mentors and instructional coaches, saw their job as supporting quality instruction that could meet a wide range of student needs at all levels of the system, rather than merely overseeing buildings, buses, and bureaucratic procedures, as many principals and superintendents have historically done. As a senior district administrator from Chula Vista observed, “I’ve seen, probably over the past 10 years, maybe 15 years, a shift in the role of the site leader, from manager to instructional leader.”

This shift put leaders in position to support teachers as they worked to include all students more deeply in meaningful learning as required by new state standards. During this change to the new state standards, district and school leaders in positive outlier districts were more than organizational managers for adults; they were involved as leaders of learning for students. Because most had had significant careers as teachers and teacher leaders and had been the recipients of the districts’ extensive and collaborative professional learning opportunities, they were prepared for instructional leadership roles. Many educators attributed their students’ successes to this sustained instructional leadership. A close look at these positive outlier districts shows that instructional leadership capacity was developed through collaborative professional learning, observation and feedback, and the use of data.

Collaborative Professional Learning

Across positive outlier districts, organizational processes engaged leaders in collaborative professional learning. This learning often promoted schoolwide, cross-school, and often cross-role collaboration. According to leaders, these strategies for systemwide sharing contributed to a culture of learning and to alignment among central office staff, principals, and teachers.

Many leaders participated in teams to share professional learning. At school sites, teams often consisted of a principal and four to five teacher leaders, charged with helping set the instructional direction for the school and developing coherence between teachers and school leaders. At the district level, teams of principals also engaged in professional learning and planning with district staff, drawing alignment between district and school leadership.

Cross-role collaboration was highly developed in Chula Vista, where the concept of professional learning communities had been extended from schools to the district office. (See “Professional Learning at Multiple Levels in Chula Vista Elementary School District.”)

Professional Learning at Multiple Levels in Chula Vista Elementary School District

Chula Vista uses professional learning communities (PLCs) at multiple levels:

- Central office administrators: Each cabinet meeting begins with discussion of a research article related to instructional and leadership topics of importance to the district. In-depth conversations challenge members’ assumptions and ensure that the leadership team has a common understanding of effective instruction.

- Principal cohorts: Lead principals and a cabinet member support a cohort of eight to ten principals. Meeting monthly, they discuss data, problem-solve, conduct school walk-throughs collecting formative assessment data, and share best practices and resources. Cohorts participate in district-led professional learning sessions, with cabinet members conducting follow-up visits and providing personalized coaching.

- Instructional leadership teams: Comprising the principal, assistant principal, and teacher leaders, instructional leadership teams attend district professional learning sessions in which they explore specific instructional practices, processes, and district-recommended protocols, and share best practices and resources to address common areas of need or problems of practice. After district-led sessions, each team determines how the content can be translated and incorporated into each school’s professional learning structures. Using a combination of assessments, teams identify areas for improvement by grade level and/or student group.

- School sites: At whole-staff sessions and in grade-level professional learning communities, teachers and coaches discuss how they take on learnings from instructional leadership teams. Grade-level teams develop performance tasks, unit tests, and interim assessments that can be used across classrooms within a grade; review student work; and identify instructional strategies and supports for student learning. Teachers are allotted time to experiment with new teaching strategies, with opportunities for peers to observe or conduct informal, nonevaluative walk-throughs and discuss implementation.

These PLCs engage in professional learning cycles, which are at the core of the district’s efforts to develop a learning organization. All Chula Vista staff members have had opportunities to engage in the elements of this professional learning cycle—direct instruction on a topic or pedagogical strategy; opportunities to practice the approach, receive feedback, and observe colleagues; professional reading on the topic, analysis of interim data, and examination of student work; measuring effectiveness; and developing plans for future professional development—although the experiences vary depending on their role.

The professional learning cycle, using research-based strategies with opportunities for professional learning at every level, contributes to fostering a culture of continuous improvement. Opportunities for safe practice, collaboration, and classroom observation support Chula Vista teachers and leaders at school sites as they engage in these cycles. These varied learning experiences, which include dialogue with their colleagues and instructional coaches, allow educators to develop their pedagogical expertise.

Other districts offered similar opportunities for collaborative learning among leaders. San Diego Unified’s district leaders and principals worked in teams to help transform district practices in accordance with the district’s equity vision. During team visits to schools, area superintendents used rubrics aligned with equity levers to inform principal goal setting, to provide leaders with feedback, and to gauge progress. San Diego leaders also engaged in Principal Institutes—whole-day professional learning events for administrators, several of which focused on developing best practices in professional learning communities.

Collaborative professional learning was not a one-shot experience in these districts. Instead, leaders continually refreshed their skills. In Sanger, despite the historically strong foundation of professional learning communities, the district continually reinvested by sending teams of principals and teachers to a professional learning community institute. Most had attended at least one of these institutes previously, but the ongoing need for repeated exposure to ideas and refreshment of knowledge was part of Sanger’s developmental approach to embed practice and build over time. This core element of the district’s philosophy of change was referred to locally as “repainting the Golden Gate Bridge.”

Observation and Feedback

Educators in positive outlier districts discussed a number of observational strategies used to engage district and school leaders in supporting and shaping instruction. These strategies varied and had different names (e.g., walk-throughs, instructional rounds, collaborative inquiry visits), but all involved leaders visiting classrooms to observe instruction. These visits helped district and school leaders support the work of teachers in the classroom and gain common understandings of effective practices in order to share them systemwide. Leaders indicated that these observations helped them gain a shared understanding of what high-quality teaching looks like while identifying problems of practice.

In Long Beach, for example, principals led by principal supervisors engaged in collaborative inquiry visits in which they observed and learned from practices in other schools, assessed a school’s progress toward goals, and shared collegial feedback and strategies on ways to meet those goals. Similarly, Sanger’s School Academic Achievement Leadership Teams of district and school administrators regularly visited each other’s schools. The teams have defined protocols for walk-throughs, combining them with data analysis and systems for feedback. These practices allowed administrators to work together across schools to identify and share a common understanding of effective practice, to conduct cross-school analyses, and to assess and iteratively improve initiatives.

Likewise, in Chula Vista, cabinet members—the senior district administrators responsible for an academic or administrative unit—were each responsible for a cohort of principals and visited school sites at least once a month. Moreover, every district cabinet meeting began with an in-depth discussion of an educational research article, building members’ understanding of instructional strategies, challenging their assumptions, and strengthening cohesion among administrators.

In positive outlier districts, these leadership teams often met monthly, but some teams met more frequently. For example, in Hawthorne, all principals were required to spend each Thursday morning visiting classrooms, a practice that has been in place for 8 years. The superintendent underscored the importance of this time for principals:

I instituted what I call sacred time. Every Thursday from 9:00 to 11:00, you won’t be called from the district office, you won’t have any interruptions from the district office. You are in classrooms, and you are walking classrooms. It’s not exclusive time, but that time is set in stone. I expect that you’re in classrooms more than that. However, it ensures that at least once a week for 2 hours, administrators are watching practice.

In a similar process in San Diego, area superintendents were also expected to visit schools, observe practice, and provide supports to principals and teachers. As one area superintendent explained, “I get up every day and I go to schools and I stay there all day long … next to leaders in classrooms, next to students.” She described the value of this process in sharing effective practices from one school to another:

I find strengths and build capacity by connecting leaders to leaders, teachers to teachers. Going inside and outside the district when we see someone who’s actually getting different results for students. Sometimes we don’t have answers and we’re not sure what to do. So, we’ll gather an integrated team and say, “How can you help us think differently about what this leader can do to support teachers, to become stronger?”

Across districts, teachers and leaders indicated that observing classrooms helped leaders develop an orientation to instruction, deepen their knowledge of the new state standards, refine their expectations for student learning, and sharpen their understanding of effective pedagogical approaches. It also helped build relationships and common understandings with principals and teaching staff, enabling leaders to support their staffs more effectively.

Use of Data

Another common thread in these districts was a deliberate, iterative approach to the implementation of new standards and deeper learning for all students. To support this approach, district and school leaders emphasized the use of a wide variety of data related to deeper learning. All the districts used California’s Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) student assessments data, which are aligned to the Common Core State Standards and include performance tasks. The districts also frequently used data about students’ attendance, feelings, behavior, and experiences to inform teaching.

Districts accessed these data through the California Department of Education dashboard. In addition to SBAC data, the dashboard includes school climate data, data on suspension rates, college and career readiness, and chronic absenteeism, all disaggregated by race, income, and language background. To these data, many of the districts also added other locally gathered data regarding conditions for learning and the allocation of resources to schools, plus examination of student work.

Data were used for three primary purposes:

- to inform instruction in the classroom;

- to target extra supports to students’ needs; and

- to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies.

While school and district leaders supported teachers in the use of data, they also played a direct role in using data.

For example, in San Diego, area superintendents and principals analyzed data to identify groups of students in need of additional support, with teachers then identifying “focus students” within these groups to examine in depth. The process of doing so helped highlight specific learning needs of these students and the teaching strategies to support their learning. A district-level teacher coach explained the rationale for approaching it in this way:

The theory behind it is that the more we pay attention to [students’] learning needs and the more we get underneath how to best meet [these needs], then [the more we can] step back and say, “What impacted the growth of this child? And let’s name that.” And then we leave the teacher with those strategies. Now [the teachers] can implement that when we’re gone. We figured out how to meet [this student’s] needs, and how do we take what we learned about [the student] and apply it [to other students], because it’s just good teaching.

In Sanger, principals present school data at annual summits with district administrators to identify improvement priorities for their schools. District leaders regularly examine student data to set priorities for improvement and evaluate policy decisions. These leaders rely on both formal and informal feedback from district and school staff to assess the effectiveness of their supports to teachers and schools. An administrator who coaches teachers explained how the district uses evidence to inform and refine policies and practices:

Sanger does well at trying new things and reevaluating and not being afraid to make changes if [something is] not working well. Always look at what’s not working for kids. We make [a strategy] our own and make it fit—we’re not about adopting programs; rather, [we] adapt and fit them to our students.

Similarly in Clovis, principals have meetings to discuss evidence, evaluate successes, and share good practices. The first of these meetings is an annual event known as the Fall Charge. Representatives from the district’s assessment and accountability department work with all area superintendents and school principals on how to use data from the state test—the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP)—for diagnostic and planning purposes.

A second kind of meeting in Clovis is known as Principal Grade Level Expectation (PGLE, pronounced locally as “piggle”). During PGLEs, school administrators report on their site’s data and, having discussed these data with their school management team, describe factors they deem responsible for their successes—a further mechanism by which good practices at one school can be disseminated to other schools.

There are multiple other structures in Clovis for data dialogue among leaders through regularly scheduled meetings, including monthly meetings for district–area superintendent and principal–area superintendent, site learning director meetings with district representatives from the departments of assessment and of curriculum and instruction, and formal and informal principal professional learning communities.

Lessons Learned and Implications for Instructionally Engaged Leadership

The seven positive outlier school districts highlighted in this brief are among the many California districts providing learning opportunities for all students in ways that promote greater equity. These district successes were made possible, in substantial part, through instructionally engaged leaders who had deep experience in their districts and participated in ongoing professional learning rooted in classroom observations, professional learning communities, and the use of student data for school and district decision-making. These districts do not hold all the answers about instructionally engaged leadership, but their approaches for cultivating leadership and using leadership to improve instruction provide lessons for local schools and districts, as well as guidance for both state and federal policymakers.

Lessons for Schools and Districts

The positive outlier case study districts are of different sizes—ranging from 2,000 to 128,000 students—and they serve different geographic locations and student populations. In these different contexts, each took a unique path toward continuous improvement focused on student learning. Yet despite these differing paths, the individual cases revealed several commonalities in the district’s approaches to leadership. All of the districts:

- Identify and develop leadership talent among current staff: The districts cultivated leadership in teachers by providing opportunities to participate in professional learning, to lead school-level professional learning communities, and, in some cases, to move into principalships. The districts also provided opportunities for principals with interest in district leadership to move successfully into central office positions.

- Involve leaders in schoolwide, cross-school, and cross-role professional learning: In positive outlier districts, professional learning teams helped leaders develop their skills. The teams also contributed to a systemwide culture of learning and to alignment among district leaders, school leaders, and teachers.

- Engage leaders in observation and analysis of instruction: Leaders in these districts had multiple opportunities to observe, study, and discuss instruction. They did this both to give feedback and to understand and support instructional change within schools and across the district.

- Ensure leaders identify needs and ground their decisions in data: Leaders in positive outlier districts used data frequently. Data informed leaders’ supports for teachers’ instruction in classrooms, helped leaders target extra school and district supports to students’ needs, and assisted in leaders’ evaluations of school and district strategies.

Guidance for Federal, State, and Local Policy

Policymakers at the federal and state levels can help ensure that all districts are able to cultivate leadership among their staff by:

- supporting the preparation of principals and district leaders who bring a strong understanding of instruction, staff development, and the productive management of change to their work;

- providing resources for professional learning grounded in participation in professional learning communities; and

- providing guidance and programmatic supports that build the collective capacity of schools and districts to teach for 21st-century standards and to meet the full range of students’ academic, social, and emotional needs.

State and federal policymakers also have a role to play in ensuring that district leaders can use helpful data to inform their work. Federal and state policy can incentivize the development and use of assessments that reflect and measure the deeper learning required by new standards. This can be accomplished through both funding for assessment development and the use of appropriate standards for approving state plans. States can then select and develop assessments that measure higher-order skills and support districts in using them, along with an array of data on other school inputs and outcomes to support student learning. States can augment these with school climate surveys for students, staff, and families to inform school and district improvement efforts and triangulate with other data. The use of high-quality assessments is essential to the success of instructionally engaged leaders like those in the positive outlier case study schools.

District-level policies and priorities play a crucial part in identifying and developing school and district leaders. At the school level, districts can provide opportunities for strong teacher leaders to further develop their leadership skills and then take on leadership roles as their skills and experience develop, with some eventually becoming principals. Districts can also involve school administrators in ongoing leadership development and create structures for some of these principals to move into the central office.

Districts can also support professional learning among leaders. This support is particularly important when leaders are implementing new instructional strategies focused on deeper learning. These supports include opportunities for classroom observation, analysis, and feedback, and participation in professional learning teams that help leaders share successful practices schoolwide and across schools, thus allowing successful practices to move throughout the district.

District policymakers also have a role to play in leaders’ use of data. Districts and schools can encourage leaders to use assessment tools, analysis of student work, survey data, and other indicators—such as attendance rates, suspensions, and evidence of student needs—to improve school climate, to shape teaching and learning, to identify and address student needs, and to evaluate school and district initiatives. This use of data was identified by leaders as a key factor in the success of positive outlier districts.

Conclusion

By definition, the positive outlier districts and leaders in our study are exceptions to the norm. They succeed in ways that are relatively rare in the system as a whole. Often, districts identified as performing at high levels are those that serve affluent, advantaged students with substantial home and school resources. These districts, however, offer few lessons to leaders working with a more socioeconomically diverse group of students and without extraordinary resources.

Our study captured lessons from California districts succeeding with African American, Latino/a, and White students and attaining high levels of achievement on assessments of academic standards in English language arts and mathematics. Among a much larger number of positive outliers in California, we chose to study districts from diverse contexts—geographically dispersed; large and small; urban, suburban, and rural—and found some common themes in district and school leadership.

We found that the leaders in these districts had deep experience and had frequently served in multiple roles—moving from classroom teachers, to building leadership, to central office leadership. The depth of leadership was not accidental; it was cultivated. Districts identified current staff with leadership potential and offered opportunities for professional learning and advancement. Once in place, these exceptional leaders focused on instruction. To do this, they engaged in schoolwide, cross-school, and cross-district professional learning teams; observed instruction frequently; and used student data for school and district decision-making. Their efforts and accomplishments show how deeply experienced, instructionally engaged leaders can shepherd schools through times of change and growth.

Instructionally Engaged Leaders in Positive Outlier Districts by Caitlin Scott, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Dion Burns is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this project and the deeper learning work of the Learning Policy Institute has been provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Cover photo provided with permission by Clovis Unified School District.