How Positive Outlier Districts Create a Strong and Stable Teaching Force

Summary

This brief summarizes successful strategies for creating a strong and stable teaching force. These strategies are drawn from “positive outlier” districts in California that have excelled at helping African American, Latino/a, and White students achieve at high levels on assessments of academic standards in English language arts and mathematics. Case studies of seven of these districts indicate several effective strategies for recruiting, developing, and retaining high-quality teachers. These strategies include a clear philosophy and effective process for teacher hiring, a well-developed teacher pipeline, a strategic long-term commitment to professional growth, and a focus on teacher retention.

The full report on which this brief is based is available here.

Teachers are essential to student success. Indeed, student achievement tends to be greater when school districts invest in teacher quality, including recruiting, developing, and retaining well-prepared teachers.Ferguson, R. (1991). Paying for public education: New evidence on how and why money matters. Harvard Journal on Legislation, 28, 465–498; Wenglinsky, H. (1997). How money matters: The effect of school district spending on academic achievement. Sociology of Education, 70(3), 221–237; Elmore, R. F., & Burney, D. (1999). “Investing in Teacher Learning: Staff Development and Instructional Improvement” in Darling-Hammond, L., & Sykes, G. (Eds.). Teaching as the Learning Profession: A Handbook of Policy and Practice (pp. 263–291). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Recognizing the importance of teachers, effective districts often establish practices and policies aimed at ensuring a strong teaching staff.Leithwood, K. (2010). Characteristics of school districts that are exceptionally effective in closing the achievement gap. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 245–291. What do these district efforts to create a strong and stable teaching force look like?

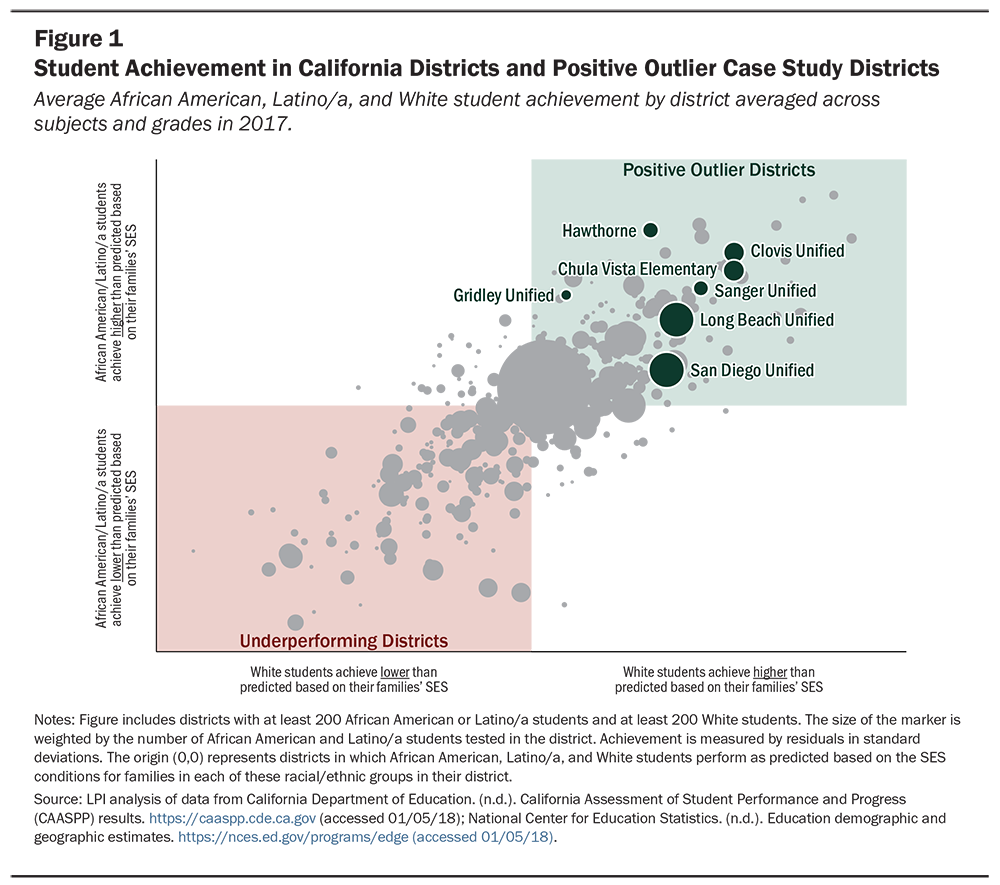

This question was addressed as part of a series of Learning Policy Institute studies. First, researchers identified “positive outlier districts” in California in which—accounting for differences in socioeconomic status (SES)—African American, Latino/a, and White students substantially outperformed their peers on California’s state assessments.The measures of district performance are the residual scores produced by a statistical model that assessed the difference between districts’ predicted California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress English language arts and math scores and their actual average scores in 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17 for African American, Latino/a, and White students. (See Figure 1.) Districts in the top right quadrant of Figure 1 were identified as positive outlier districts because African American and Latino/a students, as well as White students, excelled in both mathematics and English language arts.

In the initial analysis of district performance, which controlled for the SES of families, teacher qualifications stood out as the in-school factor most strongly associated with students’ success.Podolsky, A., Darling-Hammond, L., Doss, C., & Reardon, S. F. (2019). California’s positive outliers: Districts beating the odds. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. On average in this study, the lower the percentage of teachers with substandard credentials, including permit, waiver, or intern credentials, the higher the student achievement. In addition, teachers’ average experience level within a district was positively associated with achievement for African American and Latino/a students.

The researchers then conducted individual case studies, including interviews and reviews of administrative data, in seven of the positive outlier districts, selected for their geographic and demographic diversity. The goal was to understand more deeply the factors that may account for the success of their students, in particular their students of color. This brief describes insights about the teacher workforce gleaned from an analysis of all seven district case studies.

These districts employed a variety of purposeful strategies that focus on attracting and selecting well-prepared teacher candidates, developing their skills further, and creating working conditions that help retain these effective educators. The districts’ strategies included a clear philosophy and effective process for teacher hiring, a well-developed teacher and leader pipeline, a strategic long-term commitment to professional growth, and a focus on teacher retention. This brief summarizes the district strategies and concludes with lessons learned and guidance for policymakers.

The Positive Outlier Case Study Districts

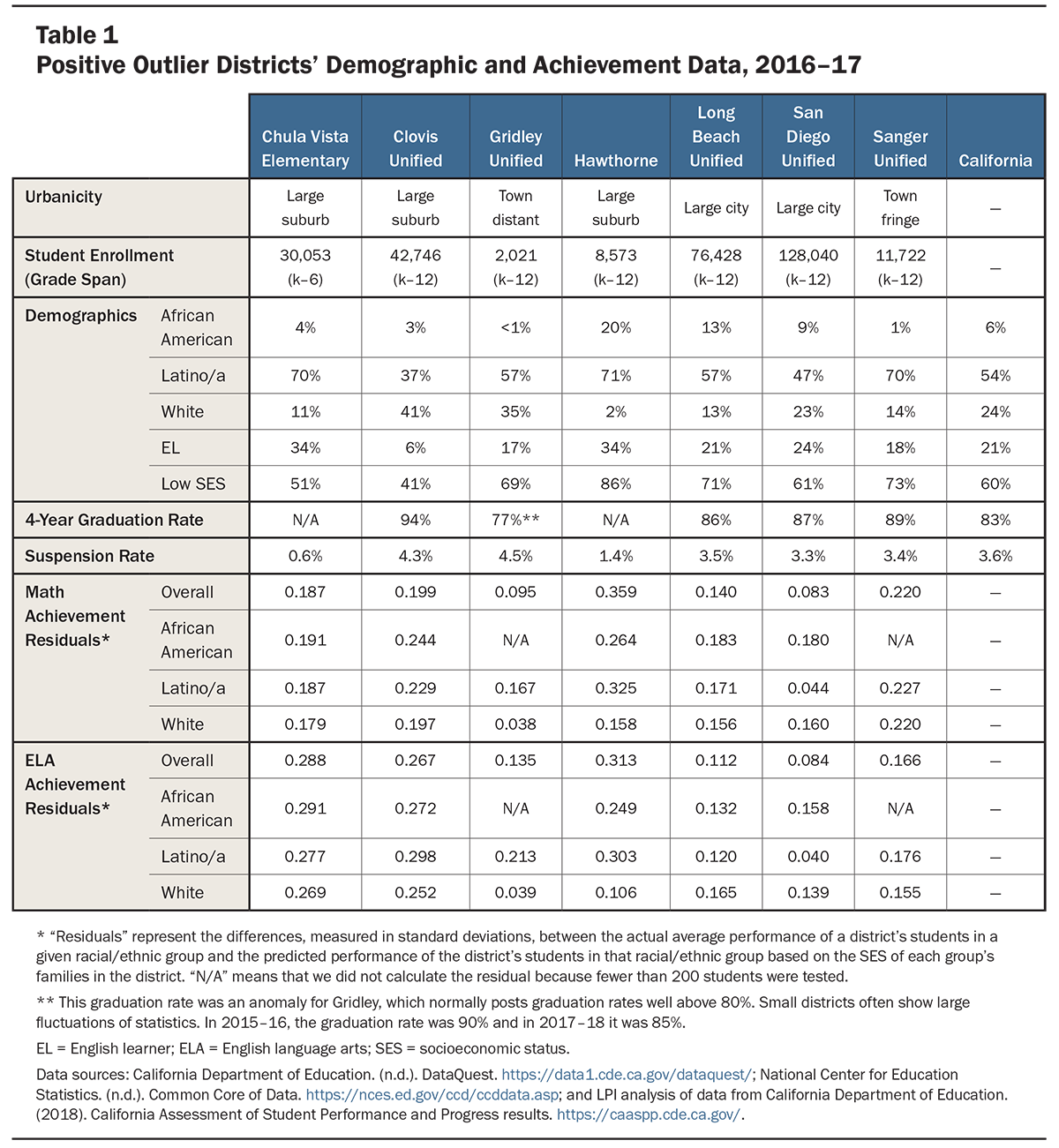

This brief summarizes lessons learned from case studies conducted at seven positive outlier school districts in California.Burns, D., Darling-Hammond, L., & Scott, C. (with Allbright, T., Carver-Thomas, D., Daramola, E. J., David, J. L., Hernández, L. E., Kennedy, K. E., Marsh, J. A., Moore, C. A., Podolsky, A., Shields, P. M., & Talbert, J. E.). (2019). Closing the opportunity gap: How positive outlier districts in California are pursuing equitable access to deeper learning. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Table 1 provides more information about these districts.

Demographics and Achievement

As Table 1 shows, the districts typically have higher-than-average percentages of English learners and/or students from low-income families, but they outperform other California districts serving students with similar socioeconomic status (SES). Achievement levels are shown as “residual” scores, which express the difference between students’ actual scores and the average performance of similar students in other districts. Any number above zero is a positive difference. Residuals near 0.2 or above are exceptional.

Stable Teaching Force

Based on an analysis of staffing data, all seven of the case study districts also have more stable teaching forces and fewer teachers with substandard credentials than is typical in California. Several of the case study districts reported that they have also been less impacted by recent teacher shortages, thanks to their low turnover.

For example, from the 2015–16 to 2016–17 school years:

- 3.5% of teachers statewide left to work in other districts, while in the case study districts the average was just 1.8%.

- 8.5% of California teachers left the state or the profession, compared to just 6.9% of teachers in these districts.

Along with these low attrition rates, the case study districts have smaller proportions of underprepared teachers, calculated based on the number of intern credentials, permits, and waivers among their teaching force. In 2016–17, just 2.5% of teachers in these districts were underprepared, as compared to 4.0% statewide.

A Clear Philosophy and Effective Process for Teacher Hiring

All the districts had well-developed hiring processes that emphasized a robust body of teaching knowledge and skills, as well as candidates’ dispositions to teach all children well. The districts involved both central office and school-level staff in making decisions about hiring—and used data including demonstration lessons as well as multiple interviews to ascertain candidates’ abilities.

Clovis Unified, a district of more than 42,000 students in Fresno County, provides an example. The district’s unique approach to hiring teachers was articulated in “Doc’s Charge,” developed by the district’s founding superintendent, Dr. Floyd Buchanan (1960–91). The document asked teachers to be role models, because developing “winning” students requires surrounding them with winning adults. It states:

We’ve got a Clovis image to keep up, and we’re looking for people a cut above the average. We’re concerned about your appearance, your attitude, your teaching skills, your ability to work with students, but most of all we’re concerned about your character and your values.

To get hired at Clovis, teachers must be committed to teaching all students, regardless of the students’ backgrounds. Teacher hiring was a staged process of between four and seven interviews plus direct evidence of teaching skill. Initial screening by school principals, typically together with a school-based panel, involved several interviews or a demonstration lesson. The principal then took selected candidates for an interview with the area superintendent. If that interview was a success, the area superintendent took the candidate for a final interview with the district superintendent, who determined whether to offer the applicant a contract.

In Chula Vista Elementary District, a 30,053-student k–6 district in San Diego County, the teacher hiring process occurred at the site level, but in a way that emulated the district’s philosophy related to hiring for leadership roles. To meet the district’s goal of cultivating a team of “A-players,” the hiring process involved defining the desired key competencies and attracting a pool of high-quality candidates. It also emphasized consensus on hiring decisions from the community to ensure the best candidates were chosen to meet community needs.

Long Beach Unified, one of California’s largest school districts, with more than 76,000 students, also emphasized teachers’ character and disposition in its hiring goals. A senior district administrator described the qualities they seek in prospective teachers:

First and foremost, we value [the applicant’s] character.… And we value the teacher who will say, “You can put me at any school” because the city of Long Beach is so diverse, … the district is so diverse, … we prefer the teacher who has that attitude that they can teach at any school.

An equity orientation was central to Long Beach’s hiring process, and the interview process sought to assess teachers’ attitudes toward teaching students of all backgrounds and levels and to hire only those who believe all students can be successful.

Thoughtful and Collaborative Development of a Teacher Pipeline

The case study districts did not wait for excellent, highly qualified staff magically to appear and knock on their doors. They used proactive strategies to develop educator pipelines. This included creating strong partnerships with initial teacher education programs and developing Grow-Your-Own strategies.

Strong Partnerships With Initial Teacher Education Programs

Several studies show that graduates of teacher preparation programs often take their first teaching assignments in familiar locations, either near where they student teach or near their hometowns.Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2005). The draw of home: How teachers’ preferences for proximity disadvantage urban schools. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: The Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, 24(1), 113–132; Krieg, J. M., Theobald, R., & Goldhaber, D. (2016). A foot in the door: Exploring the role of student teaching assignments in teachers’ initial job placements. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(2), 364–388. Most of the case study districts cited proximity to, and strong collaborative relationships with, initial teacher education programs as factors in the recruitment of teaching staff. Research also indicates that high-quality teacher preparation programs are important for teacher retention,Darling-Hammond, L., Sutcher, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Teacher shortages in California: Status, sources, and potential solutions [Technical report]. Stanford, CA: Stanford University and Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE). and several of the case study districts were notable in the ways they worked with nearby programs.

San Diego Unified, with more than 128,000 students, is California’s second-largest school district. Many of the district’s early career educators came from local universities and had typically interned or student taught in the district. The district–university relationships were built and strengthened over many years with substantive give-and-take about the nature of preparation so that teachers and leaders would be familiar with the district’s approach, including a distinctive language- and literature-rich approach to literacy development represented in both university training and district practice.

Similarly, Long Beach educators and postsecondary teacher education faculty at California State University at Long Beach collaborated to develop the coursework, fieldwork, and professional development for current and future Long Beach teachers. A district administrator commented:

It’s a nice symbiotic relationship.… Many of our students will stay within the city. They will go to Long Beach City College. They will go to Cal State Long Beach. They’ll get their teacher credential, and they’re back in our system. That, I think, is something that just creates a nice synergy over time that has gone on now for 50-plus years.

The synergy extended further because experienced educators from Long Beach Unified often went on to become instructors at Cal State Long Beach, and thus former teachers from the district were involved as instructors in the preparation of its future teachers. In addition, current Long Beach teachers often acted as cooperating teachers for student-teachers and as co-instructors in some courses. Several teachers commented that having their colleagues as teacher educators provided a smooth transition into the district for prospective teachers.

District and school representatives at Gridley Unified, a district of about 2,000 students in rural Butte County, said that close partnerships with university teacher education programs gave the district an advantage in teacher hiring. They indicated that, unlike many districts in the state and, particularly, rural districts, Gridley had not faced teacher shortages. As one principal noted, “We’re very close to UC Davis and Chico State. And so we get very good, qualified teachers. I mean, I can’t remember hiring one that did not have a credential.”

Grow-Your-Own Strategies

Long Beach was also among several case study districts to use Grow-Your-Own strategies that encouraged local youth to return to the district as teachers. As part of a long-standing agreement known as the Long Beach College Promise, Long Beach students receive their first year of study at Long Beach City College tuition free and are also guaranteed admission to Cal State Long Beach if they meet the entrance requirements. This has provided Long Beach students, including those interested in teacher education, with an incentive to undertake training locally. This strategy can have the extra benefit of helping districts diversify their future teaching workforce and ultimately their administrative workforce as well.

Clovis also used a Grow-Your-Own approach, and administrators estimated that 40–50% of teachers had themselves once been students in Clovis schools. Their Grow-Your-Own approach involved two main elements. The first was that all five high schools in the district offer an education pathway as part of their Career Technical Education (CTE) programs. The district also reported that a number of graduates of its parent academies—offered in Spanish, English, and Hmong, and primarily intended to serve as a bridge between home and school—had later gone on to work in the district as instructional aides.

A second element was that Clovis provided training for existing instructional aides seeking to become teachers. Realizing that around 50% of the district aides working in after-school and preschool programs were themselves seeking to become credentialed teachers, the district initiated a program for these staff to receive monthly professional learning in literacy instruction, lesson observation, and peer feedback.

A Strategic Long-Term Commitment to Professional Growth

The positive outlier case study districts used collaborative professional learning as a key to their implementation of the new Common Core State Standards, their improvement of student outcomes, and ultimately their retention of successful staff. They invested in a variety of supports to make their collaborative professional learning effective, including working with external coaches and analyzing student data in order to implement professional learning cycles.

Collaborative Professional Learning for Teachers

In the case study districts, processes were in place to promote collaboration in professional learning across classrooms and schools, and often across roles, with strategies for sharing practices systemwide. In each case, practice was increasingly deprivatized: It became public and shared as educators were expected to learn from one another and to develop common norms and practices, not close the door and do their own thing. (See “Professional Learning Supports in Long Beach Unified School District” for a description of collaboration in Long Beach).

For example, many of the districts used a long-standing practice—professional learning communities (PLCs)—to bring teacher teams together regularly to understand standards, plan instruction, reflect on student work, revisit lessons accordingly, and plan interventions and enrichment to ensure that all students learn.

Sanger Unified, a Fresno County district with almost 12,000 students, first invested in PLCs in 2005 as its primary strategy for turning around student performance. Their approach has evolved over time, including transitioning to a continuous improvement PLC strategy. In that context, the district invested heavily in developing teacher leadership, creating positions in schools to support teacher learning (curriculum support providers), and focusing principals on leading learning in their schools’ PLCs. PLCs have become the way of doing business among teachers and administrators alike. By 2012, the district had developed effective systems and routines for professionals at all levels who work together to ensure that all students achieve to high standards.

Chula Vista also used PLCs across multiple levels. Meetings of central office administrators included in-depth discussions of research related to instruction and leadership. Cohorts of principals met monthly to discuss data, problem-solve, conduct school walk-throughs, and share best practices and resources. Instructional leadership teams, which included school site administrators and teacher leaders, attended district professional learning sessions together and then determined how the content could be incorporated into their school’s professional learning structure. At school sites, whole-staff sessions and grade-level PLCs discussed learnings from the instructional leadership teams, and then had time to experiment with new teaching strategies, observe peers, and discuss implementation.

Professional Learning Supports in Long Beach Unified School District

In Long Beach, the approach to cross-role collaboration and professional learning engaged educators across schools to help ensure effective practices were shared. The district put a number of supports in place for this purpose.

- Curriculum specialists: A team of curriculum specialists creates curricular materials, co-teaches lessons with teachers to model instructional strategies, guides staff discussions about content and standards, and facilitates several other professional learning strategies.

- Instructional leadership teams: A principal and at least two or three teachers from each school attend district-level professional learning sessions together two to three times a year. They are expected to bring the training back to their schools to help facilitate school improvements.

- Collaborative inquiry visits: Each school is in a network with approximately three other schools. Teachers and administrators visit each other’s schools to give each other feedback in the areas they are working on and to learn about practices they might implement in their own schools. An online platform called ObserveMe facilitates scheduling of these visits.

- Unit lesson study: District instructional coaches work with teams of teachers at a school site to take a “deep dive” into what students should know and then plan a lesson together, teach the lesson while watching each other, and review outcome data to determine how to improve upon the lesson. Teachers thus practice the steps necessary to collaborate together and gain a better understanding of the standards and instructional practices needed to support student learning.

- Principal meetings: Principals attend district meetings focused on teaching, learning, and student data, especially as they relate to supporting instructional shifts. Principal meetings had existed in the district for several years, but they became more focused on teaching and learning after 2014–15.

- MyPD: The district compiled instructional resources and videos of teachers from across the district delivering lessons on different topics and addressing different standards. This convenient video platform provides personalized, self-paced courses for teachers and helps educators see what effective teaching and learning looks like in Long Beach classrooms.

- Staff meetings: A Long Beach philosophy is that every meeting is professional development. School leaders are encouraged to make sure that every whole-school, grade-level, or department meeting is dedicated to helping teachers meet the school’s goals, rather than focusing on administrative or logistical issues.

Professional Learning Cycles and Coaching

The districts took a phased approach to the implementation of the new standards, focusing first on providing time for teachers to unpack the standards and understand their expectations, then engaging in professional learning cycles to support instructional shifts. These cycles centered on using student data for three purposes: (1) to inform instruction in the classroom, (2) to target extra supports to students’ needs, and (3) to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies. Supporting teachers well through this process contributed to teacher retention.

Most districts brought on instructional coaches to support these learning cycles. In Hawthorne, which serves about 8,500 students in Los Angeles County, each school had two coaches—one for literacy and one for mathematics—who led professional learning cycles. The coaches worked with teachers to identify a focus area, meet to discuss lesson plans, observe a lesson, and meet again to guide teacher reflection on the lesson and future changes. Coaches emphasized that their role was not to judge teachers, but rather to offer support for instructional improvement. A mathematics coach described it as follows:

I’m not evaluative. I’m a peer coach.… It’s a really collaborative piece with teachers. It’s not like, “You did this great, you did this poorly.” No, that’s not my job. My job is, “If we’re going to have your kids access this curriculum, how can I help you do that?”

Along with developing internal structures and supports for improvement, the case study districts engaged with external partners such as universities, county offices of education, and nonprofit organizations. The districts were strategic in their approaches to such partnerships, identifying specific areas of learning needed and selecting partners able to provide these. The districts also favored sustained engagements with external partners over short-term arrangements, and several used such partnerships to address specific issues of equity.

For example, San Diego Unified engaged deeply with two organizations on issues of equity. One partner guided the district in analyzing barriers to more equitable enrollment in Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate classes and facilitating greater enrollment in classes that meet California’s university entrance requirements. The other partnership helped with the development of a districtwide equity vision, identifying five equity levers for change and using these to translate the vision into concrete practices. Specifically, the work brought attention to professional learning to support students of color and students from low-income families.

A Focus on Teacher Retention

The districts’ high rates of teacher retention were a function of the hiring of well-prepared teachers (who typically stay in the profession longer), of supporting teachers’ development, and of establishing a positive district culture committed to teachers’ professional growth.

In Sanger, both administrators and teachers attributed the stable teaching force to the district’s collaborative culture. In Gridley, teachers mentioned the supports they received when they needed things for their classrooms, allowing them to focus on teaching.

In Hawthorne, district leaders intentionally built relationships grounded in collaboration and shared purpose. An associate superintendent said:

I think people really feel like they play a role and their voice is heard. I think that that’s part of what makes people stay in their jobs. It’s not always the paycheck. It’s that sense of purpose, being a part of a bigger effort, satisfaction, [and] feeling valued. I feel like people feel that here.

In Clovis, several teachers and administrators talked about the systems in place to support teachers and about the culture of high performance. One teacher mentioned the district’s structures and supports to help teachers with challenges in their work. These included support staff for students’ social and emotional well-being and “transition teams” to help high-need students adjust in moving from elementary to intermediate and from intermediate to high school. He added, “[Administrators] are supportive.… If I need help, I can ask someone for some help, and I feel like they will value that question from me.”

Developing a culture and climate of support can be challenging, especially in larger districts. In Long Beach, the district has a dedicated Teacher Quality and Retention Office focused on supporting and keeping teachers. Staffing surveys revealed that teachers identified opportunities for professional development as the main reason they would choose to stay in the district.

Strategies for Building a Strong, Stable Teacher Workforce

The seven positive outlier school districts highlighted in this brief are among the leading districts in California in providing learning opportunities for all students in ways that promote greater equity. They do not hold all the answers for creating a strong, stable teaching force, but their approaches related to recruiting, hiring, developing, and retaining effective teachers provide lessons for local schools and districts, as well as guidance for both state and federal policymakers.

Lessons for Schools and Districts

The case study districts enjoy greater-than-average stability among their teachers, enabling them to avoid teacher shortages that have plagued many school districts in California. Their intentional strategies and staffing-related practices are worthy of consideration by local district and school leaders looking to build a strong and stable workforce and improve student learning.

Consistent and intentional hiring practices distinguished the case study districts. Most had a clearly articulated philosophy regarding the character and disposition of the teaching candidates they were looking for. That included a commitment to teaching all students and confidence in students’ ability to succeed. Using different approaches, the case study districts also balanced school and district input into hiring teachers and the processes they employed to do so.

Proactive strategies related to recruitment were also standard practice in the case study districts. This included the development of close partnerships with the teacher preparation programs at nearby universities. Grow-Your-Own strategies helped to feed the teacher pipeline in those programs and also support staff diversity.

Intentional efforts to develop and retain teachers included a focus on staffing, and districts built pipelines and systems to recruit and—importantly—keep good teachers. They sought and helped train strong candidates to hire, often in partnership with nearby schools of education; ensured supportive mentoring; and invested in ongoing professional learning. They identified and developed leadership talent among teachers to enable them to mentor, coach, and lead school improvement. They treated educators as a valuable resource—not as interchangeable widgets—hiring carefully and supporting them once hired. These teachers were essential to instruction as schools worked to implement rigorous and meaningful learning opportunities for all students.

Guidance for Federal, State, and Local Policy

Policymakers at the federal and state levels can support strategies and practices that strengthen the teacher workforce. To ensure that all districts are able to build and retain a similarly strong and stable educator workforce, policymakers have a responsibility both to produce an adequate supply of well-prepared teachers and to support opportunities for professional learning. These policymakers can:

- Help expand high-retention pathways into teaching that research shows can both recruit and retain teachers, such as teacher and school leader residencies and Grow-Your-Own programs that recruit and prepare diverse candidates from the community who are committed to serve there.

- Provide incentives in certain high-need fields (special education, math, science, and bilingual education) and locations, given ongoing teacher shortages in these areas.

- Invest in a strong, readily available infrastructure of high-quality professional learning opportunities that build the collective capacity of schools and districts to teach for 21st-century standards and to meet the full range of students’ academic, social, and emotional needs.

Teachers’ professional preparation and ongoing learning are vital components in developing and sustaining a strong teacher workforce. State and federal policymakers can signal this importance—and support it—by allocating funds for these purposes. In addition, at both the state and federal levels, investing in a strong, readily available infrastructure of high-quality professional learning opportunities is an effective way to build the collective capacity of schools and districts.

District-level policies and priorities play a crucial part in making the practices found in the seven positive outlier districts possible and effective. Related to hiring, district leaders should consider:

- Taking a systematic approach to building a teacher pipeline by considering all available opportunities, from the creation of teaching pathways in high school CTE programs to cultivating active partnerships with local teacher preparation programs.

- Making it a priority to hire and mentor well-prepared teachers with the disposition and commitment to teach every child and creating hiring processes accordingly, including finding the right balance between district and school input into the hiring process.

School districts can support capacity by focusing not only on outcomes but on the learning of educators to help all children meet those outcomes. These include PLCs and focused professional learning cycles to implement new instructional strategies and develop them in practice, supported by observation, feedback, and coaching. Districts can reach out to experts in areas that are the focus for improvement, while also harnessing expertise among existing staff. As seen in the positive outlier districts, these investments in teachers’ and leaders’ professional learning pay off in much stronger student learning.

Conclusion

By definition, the positive outlier districts in our study are exceptions to the norm. They succeed in ways that are relatively rare in the system as a whole. Often, districts identified as performing at high levels are those that serve affluent, advantaged students who have substantial home and school resources. Those districts, however, offer few lessons about creating a strong and stable teacher workforce that can successfully serve a more socioeconomically diverse group of students without extraordinary resources.

Our study captured lessons from California districts succeeding with African American, Latino/a, and White students and attaining high levels of achievement on assessments of academic standards in English language arts and mathematics. Among a much larger number of positive outliers in California, we chose to study districts from diverse contexts—geographically dispersed; large and small; urban, suburban, and rural—and found some common themes in district and school leadership.

We found that these districts employed a variety of purposeful strategies focused on attracting and selecting well-prepared teacher candidates, developing their skills further, and creating working conditions that help retain these effective educators. The districts’ strategies included a clear philosophy and effective process for teacher hiring, a well-developed teacher pipeline, a strategic long-term commitment to professional growth, and a focus on teacher retention. The accomplishments of these positive outlier districts show that, by acting intentionally, districts can work to create a strong and stable workforce and help ensure all students have effective teachers.

How Positive Outlier Districts Create a Strong and Stable Teaching Force by Dion Burns, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Caitlin Scott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this project and the deeper learning work of the Learning Policy Institute has been provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Cover photo provided with permission by Clovis Unified School District.