Promising Models for Preparing a Diverse, High-Quality Early Childhood Workforce in California

Summary

High-quality early childhood education (ECE) begins with well-prepared, highly qualified educators. This brief offers practitioners and policymakers an opportunity to learn from promising programs that recruit and prepare racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse cohorts of educators to teach in programs serving children birth to age 5 in California—a state that is actively considering investments to further develop its ECE workforce. It provides case studies of three distinct approaches to early educator preparation that offer innovative, affordable pathways for candidates who reflect the communities they serve and identifies their shared features. Building on insights from policies enacted at scale in New Jersey that supported similar initiatives, this brief provides recommendations for policies to better support California’s ECE workforce and strengthen its early learning system.

The full report can be found online here.

Decades of research have established that early childhood education (ECE) for children birth through age 5 can have a positive effect on children’s development and school readiness.Phillips, D. A., & Shonkoff, J. P. (Eds.). (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. See the full report for a comprehensive list of references. In order for ECE programs to support this development, they need educators who are prepared to create engaging, inclusive, and developmentally grounded learning environments and who can effectively reach and teach diverse learners. Many successful ECE programs call for educators to have a B.A. and specialized training in ECE, but California requirements are less ambitious, and access to comprehensive preparation programs is limited.Stipek, D. (2018). Getting down to facts II: Early childhood education in California. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University & Policy Analysis for California Education.

California policymakers have begun considering proposals to update credential or degree requirements for early educators. There is concern, however, that well-intentioned policies to raise educator qualifications without sufficient supports may have negative consequences for the adequacy; stability; and racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of the ECE workforce and may result in a shortage of educators.California Assembly Blue Ribbon Commission on Early Childhood Education. (2019, April). Final report. Sacramento, CA: Author. (accessed 09/28/19).

The report on which this brief is based describes three promising programs that recruit and prepare diverse cohorts of educators through innovative, affordable pathways: the Family Child Care Apprenticeship program; the Education/Child Development Program at Skyline College, a traditional community college; and EDvance, a pathway preparation program at San Francisco State University that supports students earning a B.A. in ECE. The report also identifies common features and, building on insights from policies enacted at scale in New Jersey, provides recommendations for policy.

California’s Context

In California, as in many states, preparation requirements for educators of children birth through age 5 vary widely by program. Most early educators in the state—including those who teach in licensed child care centers or preschools—must hold a California Child Development Permit, which does not require attaining a degree. Educators in Head Start must have an associate or bachelor’s degree with a specialization in ECE. Transitional kindergarten and special education preschool teachers, both of whom work in school districts, must hold a California teaching credential, which is often obtained through a 1-year postbaccalaureate program.

Early educator preparation occurs at both 2- and 4-year colleges and universities. California’s community colleges are an important resource for many early educators because they are available across the state, have low tuition relative to other institutions of higher education, and offer coursework needed to fulfill requirements for the California Child Development Permit. Many 4-year colleges and universities also have ECE programs, although only 29% focus specifically on preparing students for classroom teaching. Fewer than 40% of early childhood degree programs at 2- and 4-year colleges require supervised student teaching, despite research showing that clinical practice is an important element of high-quality teacher preparation.Austin, L. J. E., Whitebook, M., Kipnis, F., Sakai, L., Abbasi, F., & Amanta, F. (2015). Teaching the teachers of our youngest children: The state of early childhood higher education in California, 2015. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley.

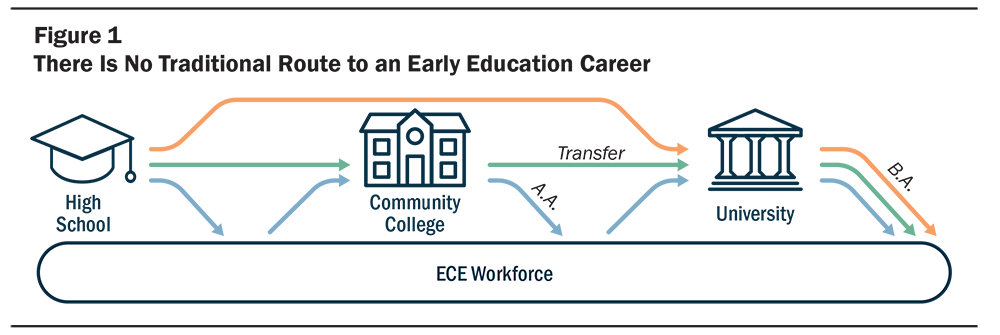

Because there is no single permit or credential to work in ECE programs, there is no “typical” path to a permit or degree. Instead, early educators enter the field with a range of education and experiences and pursue credits, permits, or degrees at various points throughout their careers. Many early educators return to school while working in the field to gain knowledge and advance their careers. (See Figure 1.)

Ensuring that early educators take efficient paths in higher education is important given that they often encounter challenges paying for school and balancing school, work, and family commitments. Further, higher education processes and systems can be complex and difficult to navigate, and college students of color and students from low-income households are disproportionately more likely to encounter these challenges.Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

The case studies in the full report offer examples of programs striving to overcome these challenges to ensure that students of all backgrounds succeed. Though each model is unique, all were selected for having a focus on preparing diverse early educators and having research-based design features, such as a focus on foundational knowledge in child development and sustained, supported clinical experience. They also represent different geographic regions.

Family Child Care Apprenticeships: Supporting Providers’ Advancement

The Early Educator Apprenticeships are an innovative pilot project aimed at increasing the qualifications of early educators through coursework paired with on-the-job training and support. The program was launched by the Service Employees International Union in partnership with ECE employers, child care resource and referral agencies, and institutions of higher education. It offers apprenticeships to locally recruited educators in three distinct settings: family child care, Head Start, and child care centers. The Family Child Care On-the-Job Training Program (FCC Apprenticeship), the focus of this case study, is designed for licensed family child care providers—small-business owners who care for children in their homes—and is implemented at four sites across California.

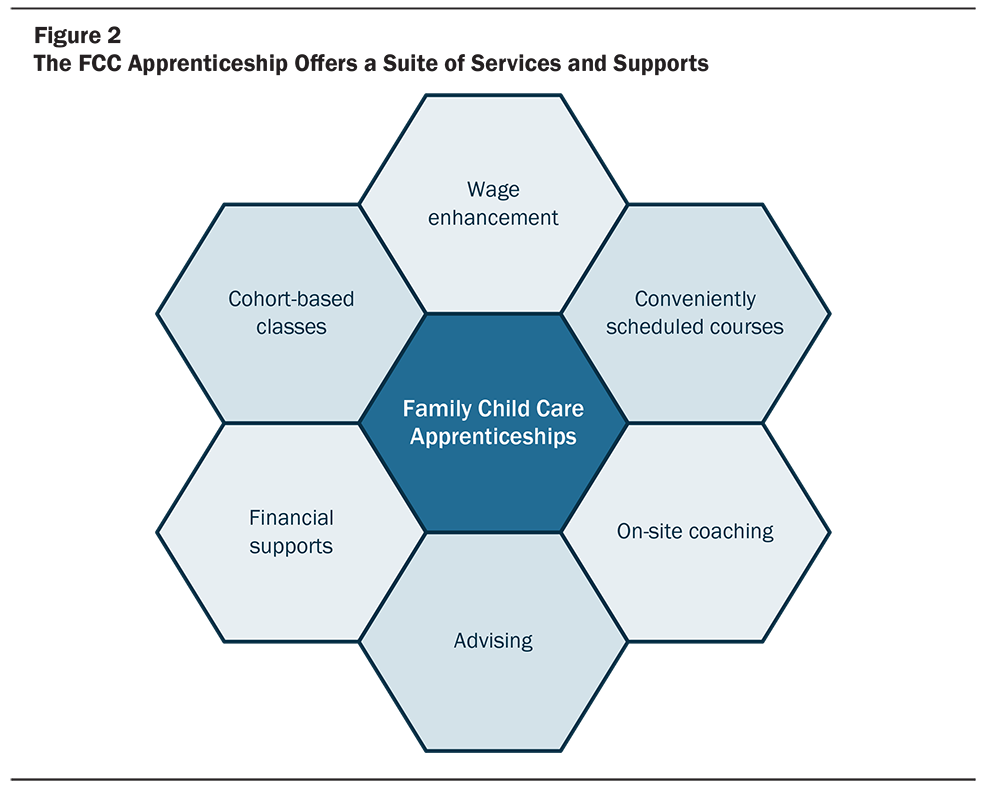

The FCC Apprenticeship helps apprentices develop as ECE professionals and acquire California Child Development Permits through accessible college coursework. (See Figure 2.) Apprentices enroll in college courses offered during evening hours at community sites, in partnership with local community colleges. Child development courses support educators’ skill development, and the program identifies required general education courses that are accessible and relevant for educators. The program has developed an onboarding process for instructors who teach apprentices, especially general education instructors who lack early childhood expertise. Apprentices are grouped into cohorts of 25 peers who act as a network of support in the classes.

The program offers bilingual and bicultural coaching from staff who visit apprentices’ homes to provide feedback and guidance on their programs and pedagogy using tools aligned with California’s quality rating and improvement system. It also provides site coordinators who help apprentices choose classes and access other support as needed.

The FCC Apprenticeship incentivizes participation by providing apprentices with a monthly wage enhancement that ranges from $100 to $500 per month, depending on their length of tenure in the program. The financial support is particularly salient for family child care providers, whose earnings are very low. The program additionally provides stipends for tuition, books, a laptop, and fees, making college coursework free for apprentices.

The layering of multiple supports into a coherent approach makes the FCC Apprenticeship a powerful learning experience, and early program data are promising. In the FCC program’s 2-year existence, 95 apprentices have earned new permits, most of whom are Spanish-speaking and identify as Latino/a. Since many of the apprentices care for mixed age groups, the approach has promise to help address California’s shortage of high-quality care for children under age 3.

Skyline College: A Community College Connecting Theory to Practice

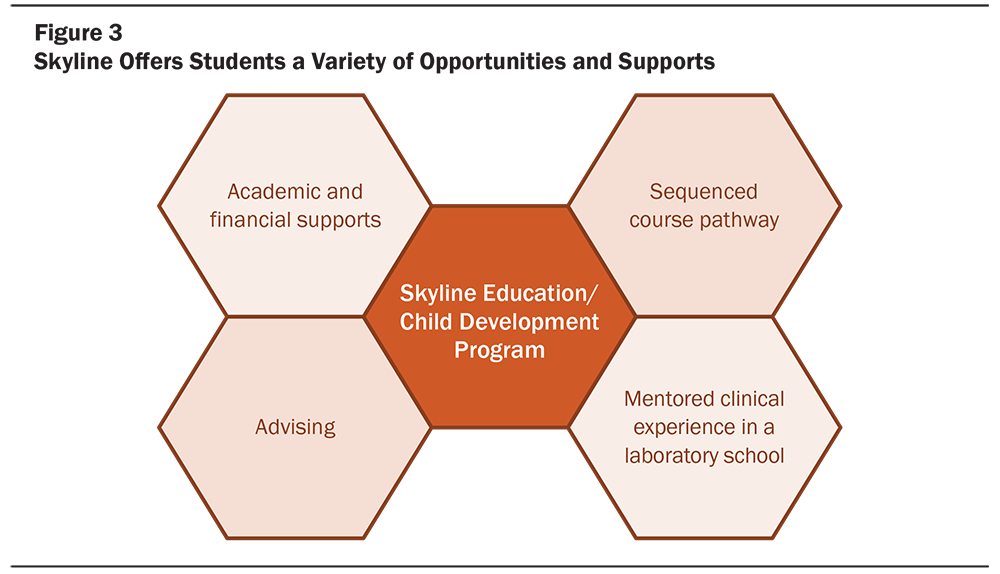

Skyline College’s Education/Child Development Program is an example of a traditional community college department creating a supportive, hands-on learning community with an explicit focus on preparing early educators for classroom teaching in a variety of settings, including child care centers and preschool programs. (See Figure 3.) It serves a range of students, from high school students to current educators, as they work toward an associate degree or California Child Development Permit.The department also offers ECE certificates, which can signify that a student has completed the coursework necessary to be eligible for a California Child Development Permit. See: Skyline College. (n.d.). Degrees and certificates. (accessed 10/29/19).

Skyline ECE courses, which are similar in content to those at other California community colleges, are responsive to the specific needs of Skyline ECE students. The program’s guided pathway offers a prescribed set of general education and ECE courses that helps students progress efficiently toward California Child Development Permits and degrees, and the college offers a general education math course specifically designed for early educators. Further, faculty use engaging teaching strategies tied to practice. Coursework is regularly modified to meet students’ needs, and faculty and staff collaboration encourages alignment of coursework and field experiences.

Skyline’s on-campus Child Development Laboratory Center, or “lab school,” provides students high-quality mentoring and teaching practice early in their academic careers. Many Skyline ECE students have some experience there through course observations, internships, or student teaching. A recently developed Teacher Track Learning Community allows some students to gain early student teaching experience and earn an Associate Teacher Child Development Permit in their first year of community college. Early experience in the classroom provides students an invaluable opportunity to connect coursework to practice. Faculty and staff meet monthly to support lab school mentors and share advice about supporting their students.

To promote student success, Skyline’s faculty and staff cultivate caring relationships with students and provide a variety of supports. ECE-specific academic and career advising helps students choose the appropriate classes to meet their goals and connects them to campus resources, and courses are offered at a low cost. While the college, like community colleges in general, struggles with meeting institutional goals to raise graduation rates, alumni speak highly of their preparation and readiness for teaching.

EDvance at San Francisco State University: Building a Pathway to a B.A. in ECE

EDvance is an early childhood teacher preparation program housed within the Marian Wright Edelman Institute for the Study of Children, Youth and Families at San Francisco State University. The program supports early educators in earning a bachelor’s degree and focuses its recruitment on groups historically underrepresented in higher education, including Black and Latino/a students.

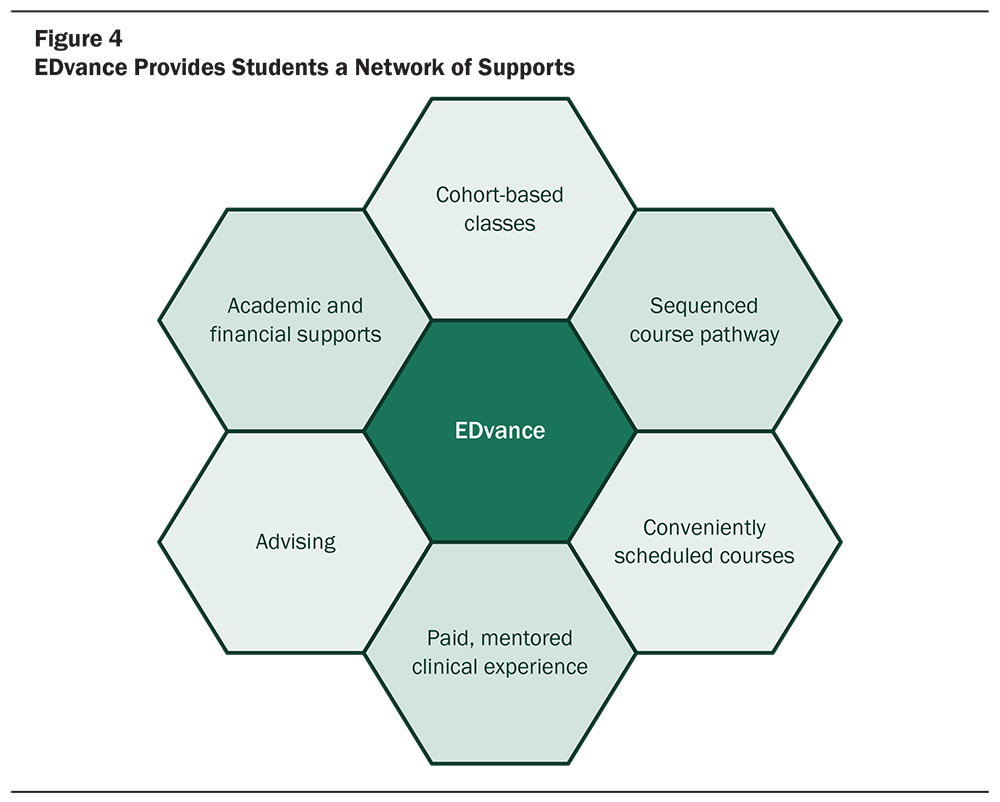

EDvance offers two thoughtfully constructed pathways for students. The lower division pathway is designed to support aspiring educators during their first 2 years of college; the upper division pathway, Promoting Achievement Through Higher Education (PATH), is for continuing San Francisco State students as well as students who transfer from community colleges. To participate in PATH, a student must work at least part time as an early educator. By the end of the program, lower division students are eligible for a California Child Development Teacher Permit and upper division students earn their B.A. In both pathways, courses are cohort-based, strategically chosen and scheduled, and incorporate a focus on social justice and equity. (See Figure 4.)

All EDvance students gain hands-on experience in early childhood classrooms. For lower division students, an early practicum program offers a supervised clinical experience in which students work one full day per week alongside a mentor teacher in a subsidized program. Upper division PATH students work at least 25 hours per week in an early childhood setting. They use videos of their work with children to reflect on their practice and get tailored feedback from faculty and peer mentors.

Across both pathways, EDvance offers specialized academic advising and educational planning, and financial aid that allows many students to attain a degree without incurring debt. These supports are offered by a team of dedicated staff and faculty, many of whom are current ECE practitioners with deep relationships with the community and are well positioned to teach students about the latest tools of the profession. They are supported by strong local partnerships and philanthropy.

EDvance has graduated more than 90% of its PATH students in just 2 years. The program provides proof of concept that 4-year institutions can provide pathways to a bachelor’s degree that support both the existing workforce and aspiring educators in preparing to teach in ECE settings.

Common Features of Promising Preparation Models

The early educator preparation models described in the report target different segments of the early childhood workforce and employ a range of mechanisms to support participants in achieving professional milestones, suggesting that there is no one approach to early educator preparation. Yet the models share the following common features:

- Local early educator pipelines and pathways. The programs have adopted highly localized recruitment strategies to target educators who reflect the diversity of local communities. The three programs have developed clear pathways aligned with recognized credentials and degrees to prepare students as effective ECE professionals.

- Relationship-building to promote persistence and success. Each program prioritizes relationship-building among program staff, faculty, and students to create safe, inclusive, and supportive learning communities. They also create cohorts of students who advance through their preparation together. The programs encourage the use of interactive and collaborative pedagogical approaches in courses to engage students, build rapport, and deepen student learning.

- Opportunities for clinical practice in feedback-rich environments. All the models provide opportunities to participate in clinical practice with support from instructors, mentors, and peers. Coursework and clinical experiences incorporate knowledge of tools and frameworks that are used in day-to-day practice in California, preparing students to work in ECE settings.

- Multifaceted supports that promote college persistence and success. Supports include individualized academic and career advising from specialized staff; courses offered on evenings or weekends in convenient locations; dedicated tutoring; courses that are intentionally sequenced and coursework that is scaffolded by instructors in response to individual students’ needs; and financial supports that reduce or eliminate higher education costs for students.

- Well-supported and diverse staffs of instructors, advisors, and coaches. Programs intentionally recruit and utilize faculty and staff who have experience in ECE classrooms and who reflect the racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of the field. They support continual professional learning opportunities and collaboration among instructors and coaches to help them deliver strong, coherent programs of study.

- Community partnerships and funding to strengthen preparation. Program staff cooperate with a variety of stakeholders, including colleges and universities, community organizations, ECE providers, and local agencies. These partnerships provide resources that they leverage to build a comprehensive system of support for students.

The features shared by these programs may be developed locally by dedicated staff who understand their local context and may also be supported at the state level, as New Jersey’s example shows.

New Jersey’s Investments in P-3 Credentialing: Preparing an ECE Workforce at Scale

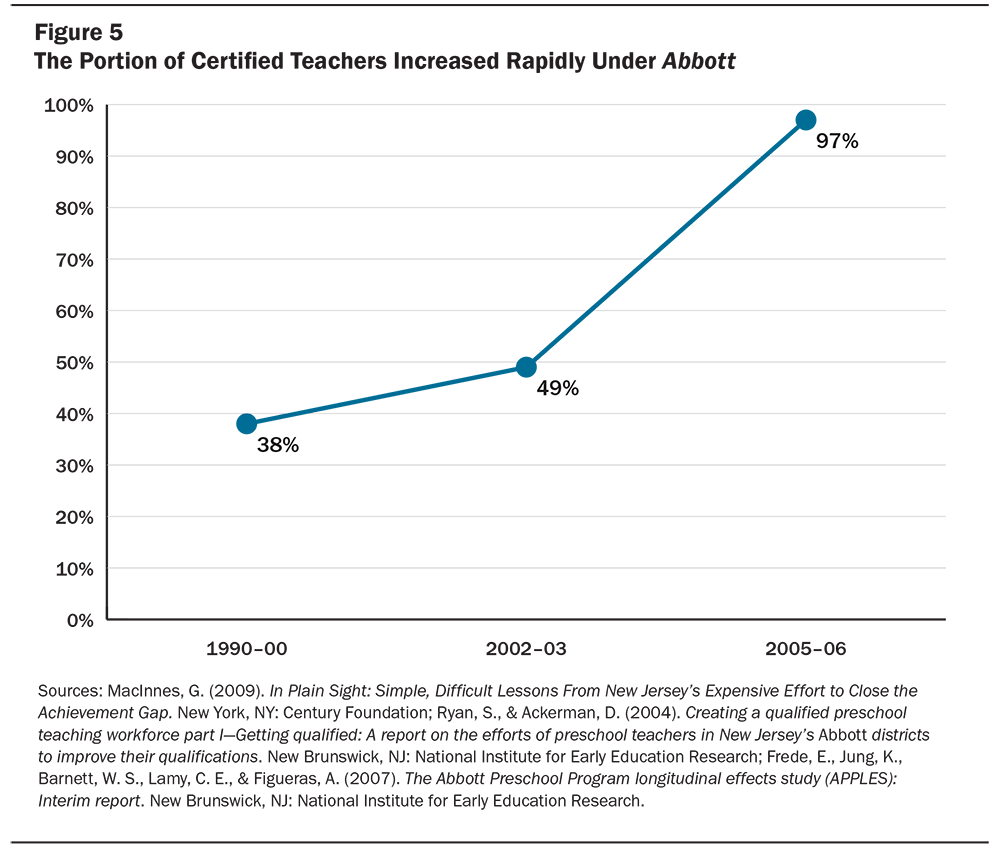

In the late 1990s, the New Jersey Supreme Court mandated in Abbott v. Burke, the state’s watershed school finance case, that the state create a high-quality, universal preschool program for 3- and 4-year-olds in 31 of the state’s poorest school districts.Students enrolled in these 31 districts made up 20% of New Jersey’s enrolled student population in 2009–10. Chakrabarti, R., & Sutherland, S. (2013). New Jersey’s Abbott Districts: Education finances during the Great Recession. Current Issues in Economics and Finance, 19(4). One of the requirements for preschool programs in the so-called “Abbott districts” was that all preschool teachers—including educators in Head Start and community-based organizations receiving state funds—hold a bachelor’s degree and a preschool to 3rd-grade (P-3) credential. The state’s policies fostered a significant and rapid shift in the supply of credentialed educators: While in 1999–2000 only 38% of preschool teachers in Abbott districts met credential requirements, by 2006 nearly all (97%) of the 2,900 teachers met this requirement. (See Figure 5.) Many of these teachers came from the existing ECE workforce.

To meet the new mandate and to build a robust pipeline of future educators, New Jersey expanded its investments in higher education and ongoing professional learning. To begin, it created multiple pathways to a P-3 credential, including traditional 4-year B.A. programs; postbaccalaureate programs; and the Alternate Route program, which allowed students with a B.A. to earn a credential while working in state preschool programs. State-funded scholarships and stipends enabled most early educators to go back to school. Finally, pay parity with k–12 teachers—mandated by the court for all teachers with P-3 certification, including educators in Head Start and private preschool centers—was a critical incentive to attract and retain educators who otherwise might leave for better-paying k–12 positions.

The state additionally expanded the size and capacity of higher education programs through two grant programs administered through the New Jersey Commission on Higher Education. The grants, totaling $13 million across preschool to grade 12 education programs, allowed institutions of higher education to develop their credentialing programs and hire more ECE faculty.Total funding was equivalent to over $18 million in 2019 dollars. See: New Jersey Commission on Higher Education. (2004). A report on outcomes of teacher education grants. Trenton, NJ: Author; Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). CPI inflation calculator. The state Department of Education and institutions of higher education also made supports available to students already working in the field, such as providing academic tutoring and advising and holding courses at convenient locations and times. State support also enabled school districts to provide extensive professional development, overseen by an early childhood supervisor and master teachers, to in-service teachers after degree completion.

High expectations, coupled with a significant increase in systemic financial support, proved to be a successful combination for rapidly raising the qualifications of the ECE workforce, and the resulting preschool program was shown to have significant long-term benefits for children.Barnett, W. S., Jung, K., Youn, M., Frede, E. (2013). Abbott Preschool Program longitudinal effects study: Fifth grade follow-up. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research. New Jersey’s preschool workforce reforms also generated lessons learned, such as the importance of developing pathways for educators without a bachelor’s degree and for educators in rural areas. Another lesson learned is the importance of gathering data to understand the implications of reforms for the diversity of the educator workforce, since data suggest that the reforms’ impact on workforce diversity was mixed across racial and ethnic groups.See full report for further discussion of how educator demographics may have shifted.

Implications for Policy

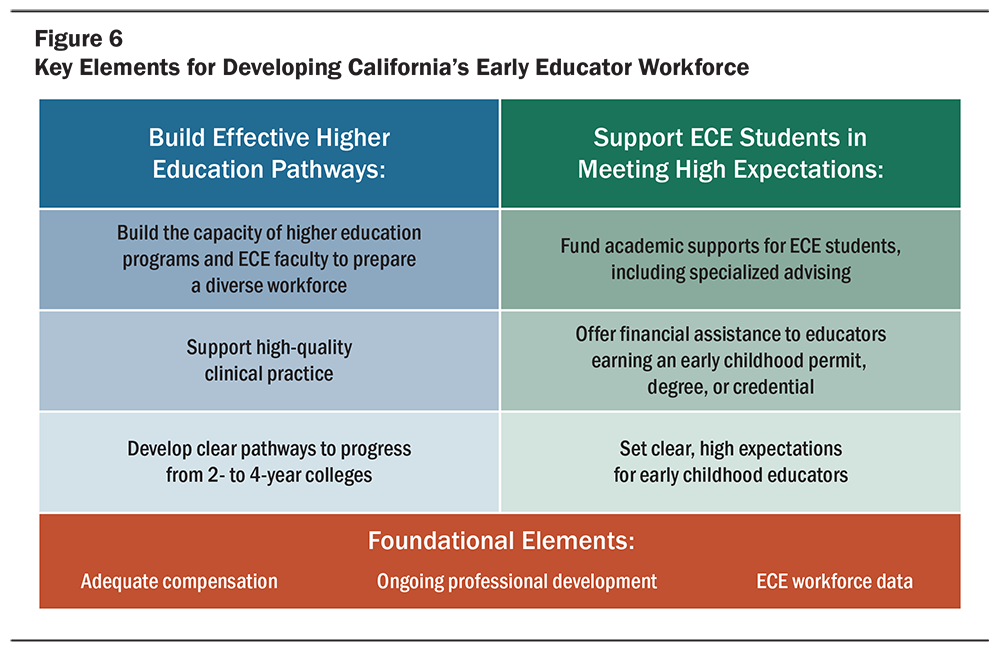

As New Jersey’s example shows, states can play an important role in ensuring that early educators have access to the supports they need to complete their higher education programs successfully. Specific steps that California can take include the following (see Figure 6):

- Build the capacity of higher education programs and ECE faculty to prepare a diverse workforce. California should consider providing institutions of higher education with funds for capacity building, as was done in New Jersey. Funding could be used to hire and train well-qualified, diverse faculty with expertise in ECE and develop high-quality content that meets the needs of diverse learners. Funds could also be used to support flexible scheduling and the provision of courses in alternative locations to make coursework accessible to more students.

- Support high-quality clinical practice. At the core of the programs described here are intensive student teaching experiences under the guidance of a mentor, yet most of California’s ECE programs do not require supervised student teaching. The state can support the development of promising models for clinical practice such as apprenticeships, lab schools, and paid practicum experiences by providing funding and technical assistance.

- Develop clear pathways to progress from 2- to 4-year colleges. Most ECE students complete their initial college coursework at community colleges. California can build upon its guided pathways and incentivize collaboration between 2- and 4-year institutions of higher education by providing funding to align course content that coherently builds students’ knowledge and skills.

- Fund academic supports for ECE students, including specialized advising. To help students complete rigorous coursework on time, especially students from groups historically underrepresented in higher education, the state can provide funding for specialized ECE advising and academic tutoring.

- Offer financial assistance to educators earning an early childhood permit, degree, or credential. Increasing financial support for early educators’ higher education, from tuition to books and student fees, is essential, particularly given the low earnings of most early childhood educators. The state budget has recently provided one-time funding for financial assistance.SB 75, 2019–20 (Calif. 2019). This is an important step, but this funding will need to be sustained over time to ensure access to all educators who need it.

- Set clear, high expectations for early childhood educators. Minimum preparation requirements in California are inconsistent across types of ECE programs, and these requirements are typically insufficient for preparing high-quality early educators. The development of an early childhood–specific teaching credential aligned to preparation standards, such as the P-3 credential in New Jersey, could significantly advance both the coherence of preservice preparation and the professionalization of the field. A formal accreditation process for ECE programs that builds on the state’s currently voluntary standards can help ensure that students’ courses comprise a coherent plan of study.

In addition to supporting educators as they increase their qualifications, California must have policies in place to retain teachers once they are in the field. Most importantly, programs must compensate early educators adequately. In a field in which educators are often paid one third the wages of their k–12 counterparts,Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L. J. E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early childhood workforce index 2018—California. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. compensation increases must accompany increases in qualification requirements or taxpayers will be filling a leaky bucket. Higher compensation was an important part of New Jersey’s success in raising the qualifications of its workforce. The state must also provide ongoing professional development to deepen educators’ knowledge and skills in the classroom. Finally, California should collect better data on the ECE workforce, including information about early educators’ higher education paths, their permit or degree completion, the barriers they encounter, and their ensuing wages. With this information, California policymakers can better understand where the state is now in terms of preparing a diverse cohort of teachers and where it needs to go.

Conclusion

ECE programs have the potential to dramatically change the course of children’s lives, especially when programs are led by highly skilled educators. The examples in this report offer lessons for policymakers about how to ensure that all children have teachers who meet high standards and who reflect the racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of young children and their families.

Promising Models for Preparing a Diverse, High-Quality Early Childhood Workforce in California (research brief) by Madelyn Gardner, Hanna Melnick, Beth Meloy, and Jessica Barajas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Photo credit: Jaqueline Eligio, EDvance.

Updated January 28, 2020. Revisions are noted here.