Promising Models for Preparing a Diverse, High-Quality Early Childhood Workforce

Decades of research have established that the first years of a child’s life provide a foundation for long-term health and well-being, and that early childhood education (ECE) for children birth to age 5 can have a positive effect on children’s development and school readiness. In order for ECE programs to appropriately support this development, they need educators who are prepared to create engaging, inclusive, and developmentally grounded learning environments and who can effectively reach and teach diverse learners. Although most ECE programs with a track record of success call for educators to possess specialized training in early childhood and a bachelor’s degree, requirements for early educators in many states are much less ambitious, and access to high-quality preparation programs is limited. As a consequence, relatively few early educators participate in in-depth formal preparation (i.e., preservice education) before they start working in the field. Instead, they may return to institutions of higher education at various points throughout their careers to learn and increase their qualifications or credentials.

A number of states are considering policy proposals to update credential or degree requirements for early educators. Practitioners, policy experts, and researchers have expressed concern, however, that well-intentioned policies to raise educator qualifications without sufficient supports may have negative consequences for the adequacy; stability; and racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of the ECE workforce and may result in a shortage of educators.

Early educators enrolled in higher education often encounter challenges paying for school and balancing school, work, and family commitments. Higher education processes and systems are complex and difficult for educators to efficiently navigate. In many states, educator qualifications vary by ECE program and are not based on a coherent career ladder, creating barriers for educators seeking to advance. College students of color and students from low-income households are disproportionately likely to encounter these challenges. Furthermore, many of the programs in which educators enroll do not focus specifically on preparing students for teaching, and many do not require supervised student teaching, despite broad acceptance of clinical practice as an element of high-quality teacher preparation.

This report is designed for practitioners and policymakers and shares the practices of promising programs that recruit and prepare diverse cohorts of educators to teach in programs serving children birth to age 5 in California—a state that is actively considering investments to develop its ECE workforce. It provides case studies of three distinct approaches to early educator preparation that offer innovative, affordable pathways to preparation for diverse candidates:

- The Family Child Care Apprenticeship: An innovative pilot project designed to increase the qualifications of family childcare providers through coursework paired with on-the-job training and support.

- Skyline College’s Education/Child Development Program: A community college-based program with a focus on preparing a range of students working towards an associate degree or Child Development Permit through a supportive, hands-on learning community and early teaching experience in a campus lab school.

- EDvance at San Francisco State University: A pathway program supporting early educators earning a bachelor’s degree, especially those from groups historically underrepresented in higher education.

Researchers examine these successful approaches alongside insights gained from policies enacted at scale in New Jersey—which rapidly increased the number of credentialed early educators—to surface valuable guidance for policymakers and practitioners nationwide seeking to ensure that all children have teachers who meet high standards and who reflect the racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of young children and their families.

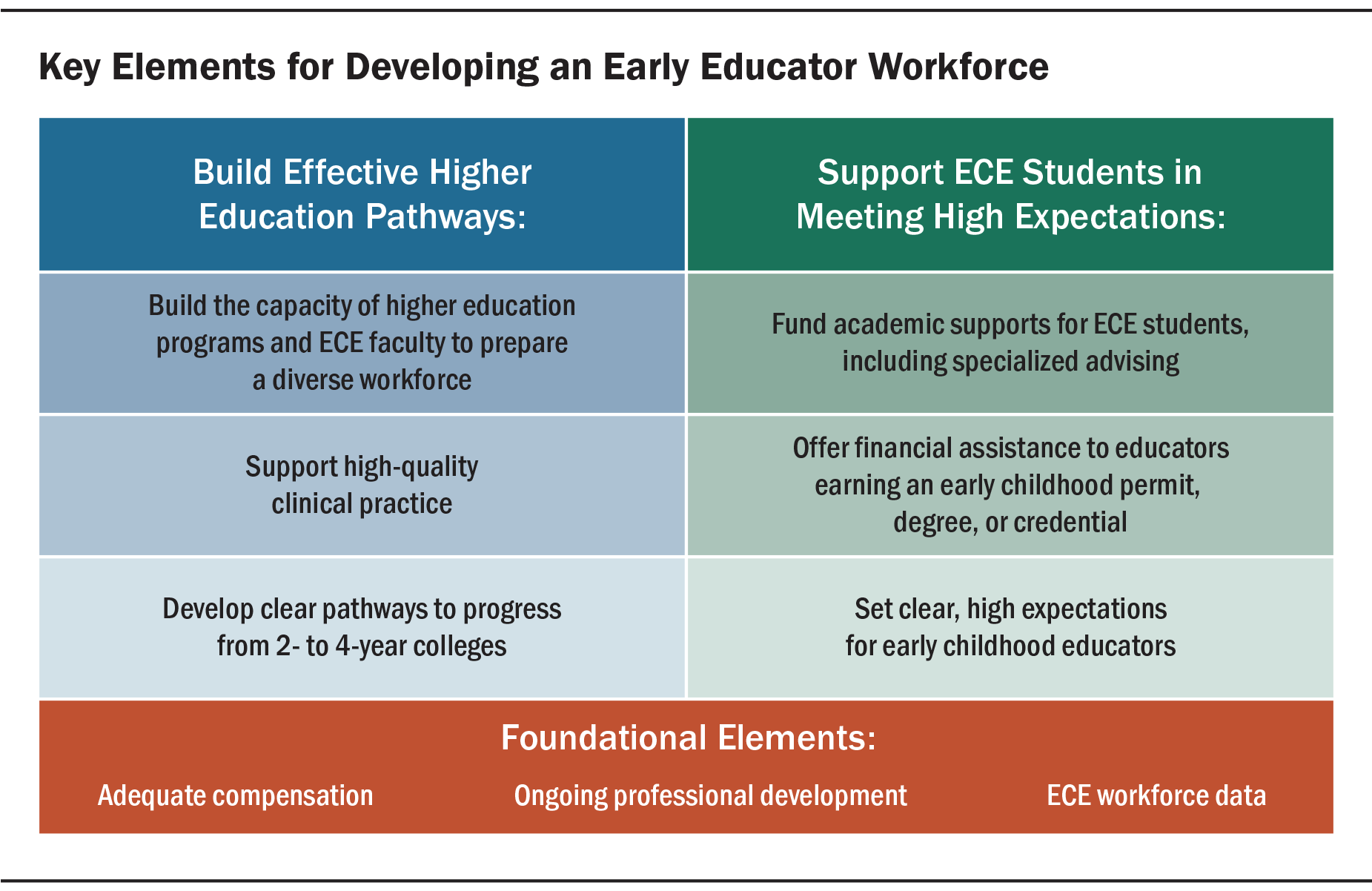

This report illustrates various ways in which these innovative early education preparation programs in California have sought to develop a diverse, high-quality workforce. The accomplishments of these programs are unusual, but they need not be. As the case study of New Jersey has shown, states can play an important role in ensuring that educator preparation is of high quality and that early educators have access to financial and other supports they need to complete their higher education programs successfully. Importantly, these supports can be made accessible to early educators across the professional continuum, from aspiring educators with no ECE experience to seasoned educators who want to further their education and expertise. Specific steps that states can take to support the educators of our youngest learners include the following:

- Build the capacity of higher education programs and ECE faculty to prepare a diverse workforce using outside funding to develop faculty and staff and continuously improve its quality. States should consider providing colleges with grants for capacity-building, including hiring and training well-qualified, diverse faculty.

- Support high-quality clinical practice. Intensive clinical experiences, including for working early educators, are essential to preparation and should be supported by instructors, mentors, and peers. States can increase the availability of these promising models by providing funding for program development and the ongoing resources needed to sustain them. States can also facilitate learning networks that allow institutes of higher education to learn from one another.

- Develop clear pathways for students to move from 2- to 4-year colleges. Many states have begun to facilitate transfer agreements with community colleges; for example, California has developed an associate degree for transfer in ECE that guarantees placement at a 4-year college. States can help incentivize collaboration between 2- and 4-year institutes of higher education to develop these pathways and align coursework by providing colleges and universities with funding to support these efforts.

- Fund academic supports for ECE students, including specialized advising. Many students in ECE programs are nontraditional students returning to the classroom after many years, and many are English learners. To help students complete rigorous coursework on time, states can provide funding for specialized ECE advising and tutoring.

- Offer financial assistance to educators earning an early childhood permit, degree, or credential. Given their low wages, early educators should not be expected to bear the financial burden of higher education costs. Increasing financial support for early educators’ higher education is essential, particularly for educators of color who disproportionately struggle with higher education costs.

- Set clear, high expectations for early childhood educators. Most states have identified professional standards for early educators that reflect the complex work of supporting young children. Minimum preparation requirements, however, are inconsistent across programs and are typically insufficient for meeting these standards. The development of an early childhood-specific teaching credential on par with k–12 credentials, such as the P-3 credential that New Jersey created, could significantly advance both the coherence of preservice preparation and the professionalization of the field. Any required credential or permit should include an intensive clinical component, which research shows is critical for professional learning. A formal accreditation process for early childhood programs can further help ensure that the courses that students take comprise a coherent plan of study.

Promising Models for Preparing a Diverse, High-Quality Early Childhood Workforce by Madelyn Gardner, Hanna Melnick, Beth Meloy, and Jessica Barajas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Photo credit: Jaqueline Eligio, EDvance.

Updated January 28, 2020. Revisions are noted here.