The Promise of Performance Assessments: Innovations in High School Learning and Higher Education Admissions

Summary

The report on which this brief is based describes performance assessments and their value for guiding and evaluating high school students' learning, as well as informing colleges and universities about what students know and can do. It explores state and local policies that support the use of such assessments, along with emerging higher education efforts to incorporate them in college admission, placement, and advising. It discusses steps that can help ensure that performance assessments are high-quality, rigorous, and well understood and that can facilitate the use of these assessments in higher education decisions.

If ever the time was ripe for colleges to consider admission criteria that measure deep learning and its application to real-world problems, it is now. Policymakers, educators, and business leaders have emphasized the need for instruction and assessments that reflect the complex thinking and performance that are necessary in today’s world. A 2015 survey of employers by the Association of American Colleges and Universities noted that:

When it comes to the types of skills and knowledge that employers feel are most important to workplace success, large majorities of employers do NOT feel that recent college graduates are well prepared. This is particularly the case for applying knowledge and skills in real-world settings, critical thinking skills, and written and oral communication skills.Hart Research Associates. (2015). Falling short: College learning and career success. Selected findings from online surveys of employers and college students conducted on behalf of the Association of American Colleges and Universities. Washington, DC: Hart Research Associates.

Meanwhile, more than 900 4-year colleges and universities—believing that current tests do not sufficiently reflect these skills—have made scores from tests like the SAT and ACT optional while emphasizing the importance of essays and other work samples, plus high school classroom performance.See http://www.fairtest.org/university/optional for a full list of colleges and universities that are “test optional,” “test flexible,” or that de-emphasize the use of standardized tests in admissions decisions. And research has shown that authentic measures of student work—from high school grade point average (GPA) and/or class rank to the SAT II writing test—are stronger predictors of college success than multiple-choice measures.For a summary, see Camara, W. J., & Echternacht, G. (2000). The SAT[R] I and high school grades: Utility in predicting success in college. Research Notes. New York, NY: College Entrance Examination Board. However, for a critique of the methods typically used in these studies, suggesting that more accurate methods would show lower correlations between test scores and college performance, see Rothstein, J. (2004). College performance prediction and the SAT. Journal of Econometrics, 121(1–2), 297–317. Also see: Geiser, S., & Studley, R. (2001). UC and the SAT: Predictive validity and differential impact of the SAT I and SAT II at the University of California. Oakland, CA: University of California Office of the President; Gesier, S., & Santelices, M. V. (2007). Validity of high-school grades in predicting student success beyond the freshman year: High-school record vs. standardized tests as indicators of four-year college outcomes. Berkeley, CA: Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of Berkeley. A recent study of 33 “test optional” colleges found that student outcomes were not undermined by the policy: college GPAs were best predicted by high school GPAs, despite wide variations in students’ test scores.Hiss, W., & Franks, V. (2014). Defining promise: Optional standardized testing policies in American college and university admissions. Arlington, VA: National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Several consortia of colleges have emerged to encourage and help develop new methods of recognizing student accomplishments. At the same time, a number of states, districts, and networks of public and private high schools have begun to identify competencies associated with college, career, and civic readiness that they evaluate with performance assessments, which are often assembled into a graduation portfolio that documents students’ accomplishments in authentic ways. As doctoral students do with dissertations, students often defend their projects and papers before panels of judges, who rigorously evaluate them against high standards; students revise their work until they meet the standards. Educators engaged in this work believe that such performance assessments provide a more holistic and accurate view of students’ mastery of critical skills while better preparing them to engage in college-level work.

If designed and used appropriately, such performance assessments could be a key component of k–12 systems and could, along with rigorous curriculum and high-quality instruction, drive improvements in teaching and learning. If organized in an easily reviewable form, results from rigorous, validated, high-quality performance assessments could be used for college admission as well as for placement or advising decisions, as an additional source of information about students’ achievements and potential for postsecondary success.

As we describe in the report on which this brief is based, these assessments also have promise for better reflecting the achievements and potential of historically underserved students, responding to concerns raised by many stakeholders about racial and socioeconomic gaps in standardized test scores. Many colleges have expressed interest in having access to such information and in developing and knowing students’ qualities of character, commitment, and resilience. They see the need to increase college access and success, especially for underrepresented students and are moving toward broader explorations of student knowledge, qualities, and skills.

By including performance assessment results in admission, placement, and advising decisions, colleges can create demand for improved learning and more authentic assessment in the k–12 system. A k–12 system focused on developing higher order thinking and performance skills, in turn, would help meet higher education’s need for a broader, deeper pool of well-prepared students.

But much work remains to make the use of such assessments in college admission, placement, and advising more widespread and practical. And much work remains to bridge k–12 and higher education efforts around performance assessment.

The full report on which this brief is based outlines current trends, progress, and possibilities for fostering more authentic ways to assess students’ competencies and mastery of skills needed for college, work, and civic life. Drawing on a review of relevant literature and extended interviews with 30 k–12 and higher education leaders, the report offers concrete examples of performance assessments and their value. It highlights efforts to develop such assessments in k–12 districts, public high school networks, and independent schools, and it explores state and local policies bolstering such practices. It examines emerging efforts in higher education to go beyond standardized tests in college admission, placement, and advising, and it maps the opportunities and challenges associated with greater inclusion of performance assessments in those areas.

What Are Performance Assessments and Why Do They Matter?

Anyone who has completed a road test for a driver’s license has experienced a performance assessment and understands why it is an essential complement to the written driver’s test. Performance assessments in education range from essays and open-ended problems on sit-down tests to classroom-based projects that let students demonstrate skills such as research, collaboration, critical thinking, technology application, and written and oral communication. These assessments may be highly individualized, or they can be designed, like a driver’s license test, as structured tasks with common elements that are used across classrooms and reliably scored with common rubrics. Performance assessments in high schools often take the form of a research investigation or capstone project during the senior year; they may include a curated collection of student work assembled into a portfolio that demonstrates a set of competencies for graduation. Performance assessments have been used for decades in the Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB) programs in high schools nationwide.

The strength of performance assessments—and the source of their validity—is their authenticity. Performance assessments are themselves learning tools that can build students’ abilities to apply knowledge to complex problems while also helping students develop co-cognitive skills such as collaboration, grit, resilience, perseverance, and a growth mindset. Students who experience a steady diet of inquiry projects linked to performance assessments ultimately perform better on measures of higher order skills.Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2014). Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Performance assessments also tend to be more valid measures of higher order thinking and performance abilities than multiple-choice measures.Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2014). Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

K–12 Innovations: From Capstone Projects to Mastery Transcripts

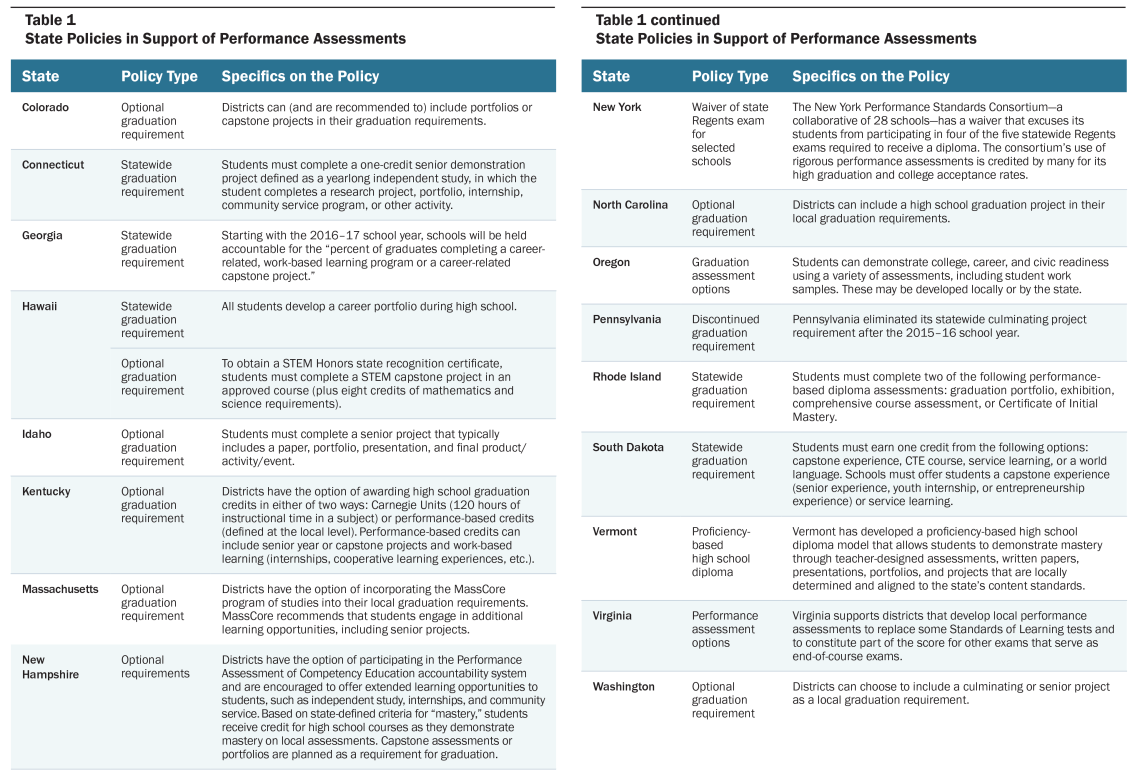

At least 17 states currently encourage or require performance assessments as part of assessing college and career readiness and graduation competencies. Some require or encourage research or capstone projects; others use collections of evidence organized into structured portfolios (see Table 1).

Complementing this state policy work are local initiatives led by districts and consortia of schools, from the New York Performance Standards Consortium (NYPSC), which has been using performance assessments and graduation portfolios for two decades, and the California Performance Assessment Collaborative, to school networks such as the Internationals Network for Public Schools, the New Tech Network, the Asia Society’s International Studies Schools Network, and Envision Schools. Many of these local initiatives have garnered promising results in high school graduation and college persistence rates, including among historically underrepresented students. Although performance assessment systems differ in their details, common principles (as outlined in the report) can make them rigorous and relevant for students.

For example, Envision Schools, a network of three schools in the San Francisco Bay Area, has a portfolio defense model that gives students several opportunities over their high school careers to demonstrate their mastery of leadership, communication, and analytical and research skills. Envision’s methods result in 80% of students, most of them students of color and students from low-income families, attending 4-year colleges and universities, with a persistence rate of 90% from year one to year two.Maier, A. (2017). Performance assessment profile: Envision schools. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

In the private school sector, more than 100 independent schools have joined the Mastery Transcript Consortium, a new effort to replace letter grades with mastery credits and to “change the relationship between preparation for college and college admissions for the betterment of students.”Mastery Transcript Consortium. (n.d.) Our Vision. https://mastery.org/who-we-are/our-story/. The vision is for transcripts to include a definition of mastery for each credit that is set by individual schools, but in a standardized format. The work underlying the credits would be visible in an electronic portfolio. For example, the transcript might show a student receiving a credit for persuasive writing. A click on that credit would take the viewer to the student’s website, where the writing could be found, along with a rubric showing the institutional standard used to judge the student’s work and provide feedback. Consortium leaders report the plan has garnered positive feedback from college deans.

Across these various efforts, the performance assessments are designed to assess student mastery of 21st century skills and competencies within core subject areas, requiring students to demonstrate their command of content knowledge. In addition, some school networks have developed systems to validate mastery using well-defined, standardized rubrics that anchor the tasks. All innovations cited include an extensive process of teacher feedback and student revision and reflection, which is critical for the performance assessment’s educative and measurement goals.Espinosa, L., Gaertner, M., & Orfield, G. (2015). Race, class, and college access: Achieving diversity in a shifting legal landscape. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

The appetite for performance assessments is growing. Notably, college admission leaders’ demand for assessments that measure deep learning led the College Board in 2014 to roll out its AP Capstone program, a 2-year program of seminar and research courses evaluated through a portfolio of student work that is scored by teachers both internal and external to the classroom.

Higher Education Innovations: Expanding Traditional Measures in Admission

“Holistic review” in admission refers to considering the entire person using a variety of information sources, not just grades and test scores. Today it is the most common selective admission approach largely because it fulfills institutions’ need to make more nuanced, individualized admission decisions from an ever-growing applicant pool. It is at least partially aimed at benefitting students (including historically underrepresented students) for whom traditional college admission measures may not adequately reflect the breadth and depth of their preparation, but whose special talents and interests would positively contribute to the college community. In a 2015 study of enrollment officials at 338 4-year institutions, the vast majority of respondents reported using holistic review in admission and noted that its use was effective in achieving institutional goals.

Performance assessment seems a natural fit with holistic review. And two key studies show beneficial results from performance assessments in both predicting first-year college success and diversifying the student body by identifying underrepresented minorities with the skills to succeed in college. The Rainbow Project, funded by the College Board, collected data from more than 1,000 high school seniors and college freshmen using multiple-choice items, open-ended tasks, the SAT, original problems, and performance-based measures to assess practical, analytical, and creative skills.Sternberg, R. (2006). The Rainbow Project: Enhancing the SAT through assessments of analytical, practical, and creative skills. Medford, MA: Tufts University. This assessment was found to be twice as good as the SAT in predicting college GPA and reducing racial-ethnic group differences relative to the SAT. A second initiative, the Kaleidoscope project, used optional questions on the Tufts University admission application to test for creativity and intelligence, and indeed predicted extracurricular and leadership involvement for students while demonstrating that greater numbers of underrepresented students of color possessed the skills to succeed in college.Sternberg, R. (2008). Assessing what matters. Educational Leadership. 65(4), 20–26.

Colleges already using performance assessments in admission include the City University of New York (CUNY), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the University of Michigan Ross School of Business. CUNY collaborates with schools from the NYPSC to ensure students are considered for admission, despite lacking test results from the New York Regents examinations (all but one of which are waived for consortium schools). Instead, NYPSC provides CUNY a robust package of transcripts, personal statements, letters of recommendation, and performance-based assessment tasks that the consortium believes offers a nuanced and thorough portrait of each candidate’s academic abilities. The latter two institutions have adopted portfolio initiatives, including MIT’s 2013 “Maker Portfolio” supplement to the undergraduate application (complementing existing portfolios in performing arts and art/architecture).

Several national efforts seek to expand the evidence used in admission. The College Board Admissions Models Project has identified nearly 30 academic factors and almost 70 non-academic factors that an institution can weigh.See College Board, Future Admissions Tools and Models Initiative, at https://professionals.collegeboard.org/higher-ed/future-admissions-tools-and-models-initiative. Part of Harvard University Graduate School of Education’s Making Caring Common project includes urging colleges to consider making admission tests like the SAT and ACT optional and pursuing changes to the Common Application so colleges can recognize a broader range of student contributions to family and community.Making Caring Common. (2016). Turning the tide: Inspiring concern for others and the common good through college admissions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Education. Over 130 selective colleges and universities are part of the emerging Coalition for Access, Affordability, and Success, which seeks to create a new pathway for college admission with an eye to supporting underresourced students. The effort includes a free online “digital locker” for students to build their admission portfolios; by 2017–18, some 113 institutions planned to accept the coalition application.Coalition for Access, Affordability, and Success. (2017). 113 colleges and universities plan to accept the coalition application this fall. https://www.coalitionforcollegeaccess.org/mycoalition-intro (accessed 12/21/17).

Using K–12 Performance Assessments to Inform Higher Education Decisions: Opportunities and Challenges

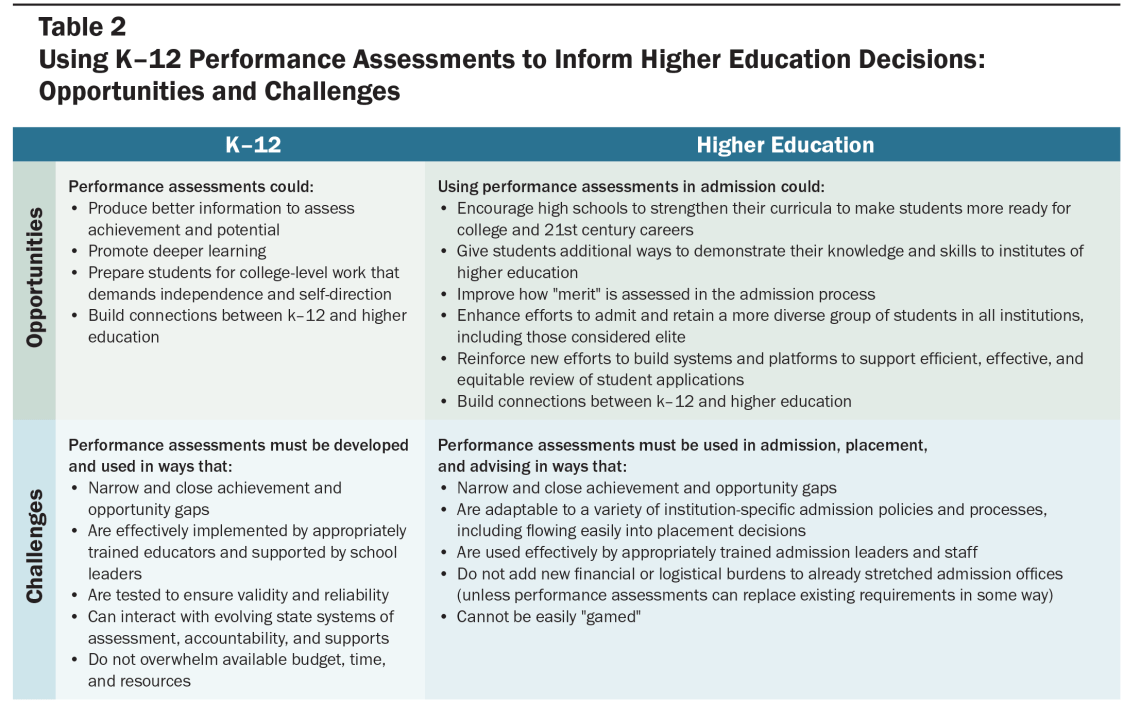

Performance assessments have the potential to enhance college education admission, placement, and advising—and to help both the higher education and k–12 sectors improve their ability to deliver on their mission-based educational interests and goals. Adopting performance assessments more broadly will require both k–12 and higher education to consider various opportunities and challenges that may be ahead, summarized in Table 2.

Making Performance Assessment Manageable for Higher Education Admission, Placement, and Advising

Given the sheer volume of applications today’s college admission officers must review, making complex information readily understandable, recognizable, and efficient to utilize for admission decisions is critical. Two concepts show promise for potential widespread adoption among colleges for admission, placement, and advising decisions.

- A standardized, competency-based transcript, such as that envisioned by the Mastery Transcript Consortium.

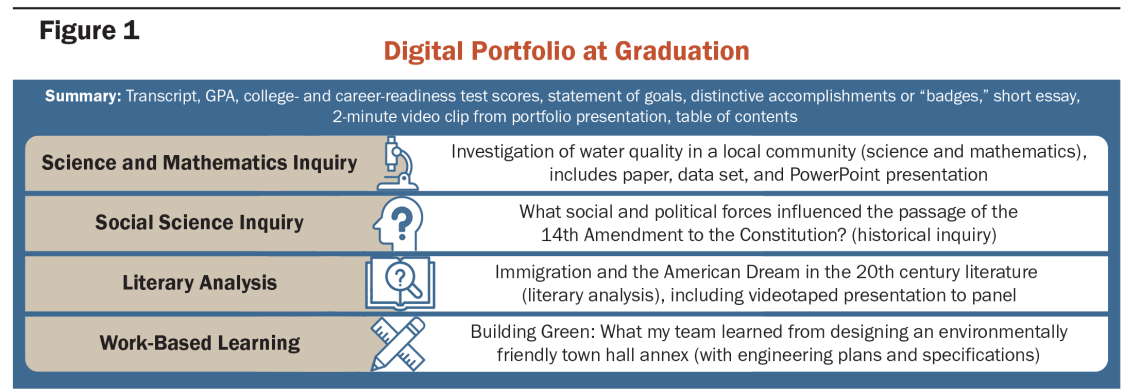

- A digital portfolio at high school graduation, such as Figure 1 illustrates. This could give a quickly readable summary of student evidence, coupled with a table of contents for easy access to selected artifacts and their scoring rubrics and evaluations. If such a system emerged as an additional “common app,” it could allow for more widespread use of authentic evidence of student accomplishment.

Looking Ahead

To help performance assessments be useful in communicating students’ abilities to colleges and universities in the field, k–12 and higher education together could do the following:

- Create a process, standards, and/or body to recognize high-quality k–12 performance assessment systems at the national and/or state level, to allow higher education institutions to understand the meaning of scores from such systems (as they do with IB and AP programs, for example).

- Design or evolve a technology-based platform, such as a digital portfolio, to capture student performance more effectively for admission, placement, and advising.

- Support a network of leading states, districts, and higher education institutions to allow k–12 school systems with strong performance assessment systems to engage more deliberately with higher education and policymakers to strengthen those systems and their use.

- Launch a communications effort to build greater awareness and understanding of performance assessment and its potential for strengthening student learning and bridging k–12 and higher education.

- Conduct research on topics such as the effect of high-quality k–12 performance assessment systems on postsecondary and career outcomes.

Such joint efforts have the potential to elicit broader changes than simply informing college admission, placement, and advising decisions. They could help k–12 and higher education better align on expectations for college and life readiness, develop new ways to identify student talent and potential (especially in historically underrepresented student populations), and create education systems that better meet today’s demands.

Well-designed and appropriately used performance assessments have the potential to help drive improvements in k–12 teaching and learning. Such assessments can help focus the k–12 system on developing students’ competencies and their mastery of the skills needed for college, work, and civic life. By including performance assessment results in admission, placement, and advising decisions, colleges can help incentivize k–12 use of such practices and, in doing so, increase the quality of education students receive and their chances of success in college and in life.

The Promise of Performance Assessments: Innovations in High School Learning and Higher Education Admissions (research brief) by Roneeta Guha, Tony Wagner, Linda Darling-Hammond, Terri Taylor, and Diane Curtis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.