Preparing Teachers to Support Social and Emotional Learning

The evidence is clear: Social and emotional skills, habits, and mindsets can set students up for academic and life success. Given that decades of research show that a focus on social and emotional learning (SEL) can lead to positive outcomes, from increased test scores and graduation rates to improved prosocial skills that support student success in school and beyond, SEL is now considered part of a whole child education. It is less clear what schools and teachers can do to develop these abilities.

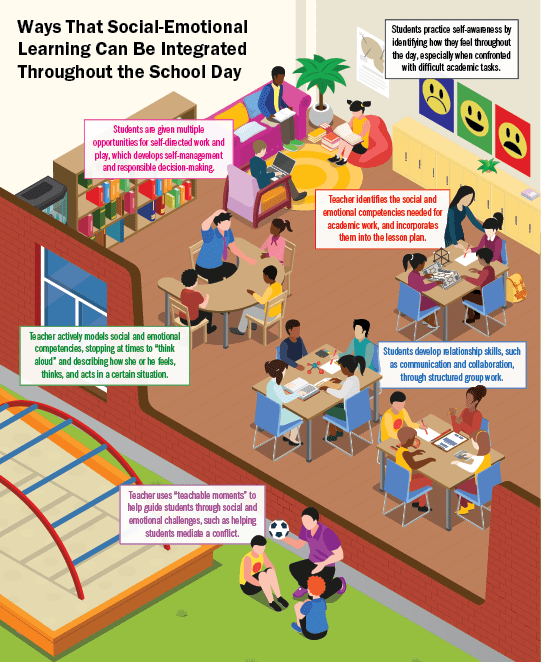

This two-part study offers information on how preservice and in-service teacher training can support good teaching practices and implement SEL in schools, while providing a picture of what SEL looks like when integrated into the school day. The first part describes how one preservice program prepares teachers for the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning, focusing on San Jose State University (SJSU)’s elementary teacher preparation program. The second part provides a glimpse into in-service professional development for SEL in Lakewood Elementary School in Sunnyvale, CA. This report is the first in a series intended to inform policymakers, practitioners, and teacher educators about the components of strong, SEL-focused teacher preparation and development programs.

SJSU’s elementary teacher education program, which graduates 125 students annually, has had an explicit focus on SEL since 2009, when a faculty member founded the Center for Reaching and Teaching the Whole Child (CRTWC). With the help of the Center, the elementary education department has been working to integrate a focus on the “social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning” throughout its program, from courses on foundational theory and academic curriculum to fieldwork.

SJSU and CRTWC’s philosophy is based on the belief that education ought to address the whole student and that development is shaped not just by schools but by one’s sociopolitical, cultural, community, and individual context. Teachers are an important part of this social context: How teachers relate to their students, and the model they set for classroom interactions, affects students’ receptivity to learning and their own social-emotional development.

Lakewood Elementary School has long had an interest in SEL, in part because it has hosted many of SJSU’s teacher candidates in their student teaching and hired many graduates. It has also developed a partnership with the CRTWC, which conducts districtwide trainings for cooperating teachers—the teachers who mentor student teachers—on the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning. Lakewood strives to ensure that teachers feel empowered to learn at their own pace and direct their own learning, while having a strong commitment to supporting students’ needs. Many teachers at Lakewood have received training on how to infuse SEL in their teaching at SJSU or in professional development with CRTWC, and those who have not are learning from their colleagues.

The research found that teacher preparation programs, such as the one at SJSU, are a logical place to begin educating teachers on the role of emotions and social relationships in learning, appropriate expectations for children's and adolescents’ social and emotional development, and ways teachers can support students’ growth in this area. Faculty at SJSU, with the support of former colleagues at CRTWC, have focused on the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning as a core part of their teacher preparation program. When SEL is a key pillar of the school’s mission, as it is at Lakewood Elementary, teachers and leaders understand that SEL should be integrated into every aspect of the school, from explicit classroom instruction and infusion into academic content to school climate and culture. In this case, teachers can continue to grow their practices as they collaborate, learn from each other, and use SEL data to make instructional decisions, with the ultimate goal of nurturing students’ social, emotional, and academic learning.

Research Findings

Implications for Preservice Teacher Education Programs

- Develop teachers’ social and emotional competence. Doing so helps them support students’ social and emotional development, and increases the likelihood of teacher retention.

- Help teacher candidates set the stage for SEL by teaching them to develop safe, inclusive, and supportive classroom environments. The science of learning and development is clear that students thrive socially, emotionally, and academically in a safe and supportive learning environment.

- Integrate the teaching of SEL into the teaching of academic subjects. Social and emotional competencies can be woven into the teaching of core academic content and curriculum, moving beyond the common misconception that SEL is taught through stand-alone lessons.

- Develop strong university-district partnerships to improve a focus on the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning throughout the teacher preparation pipeline. During student teaching, teacher candidates must apply the multiple theories and strategies they have learned in their coursework. For these experiences to be successful, teacher candidates should be able to see their cooperating teacher model good teaching that is attentive to SEL.

- Provide time for faculty for training and collaboration to integrate practices that support SEL effectively in their coursework. Faculty need time to participate in trainings, read, inspect their own syllabi and assignments, and collaborate with each other. Integrating SEL into a preservice program requires time for the whole staff to develop a common language and commitment across the curriculum.

Implications for Schools

- Integrate SEL into the fabric of the school. All adults, from leadership to support staff, need to understand the importance of SEL and know how to support it. SEL is seen not as something that is done through discrete lessons, but rather as something that contributes to students’ development.

- Start with the social and emotional learning of the adults. When teachers and principals are aware of their own emotions and how these emotions impact the classroom and school environment, they are more likely to support students in understanding their own emotions.

- Create explicit opportunities to generate buy-in and engage teachers in making decisions about SEL implementation. Educators are a key component of any SEL initiative; without their buy-in and commitment, resources allocated for SEL implementation could go to waste. By creating opportunities for teachers to learn about SEL through trainings, observing colleagues at their school or district, or attending conferences, educators can be active participants in making decisions about how SEL is implemented at their school.

- Create professional development on SEL that is explicit, sustained, and job-embedded. Teachers, counselors, coaches, and other professionals working in schools benefit from training on how to teach social and emotional competencies and how to infuse SEL in teaching practices. As with all good professional development, follow-up and coaching are important components of educator learning, which ideally is differentiated based on the educator’s experience and prior exposure to SEL and the needs of the student population being served.

- Provide ongoing support to educators using SEL assessments for instructional purposes. SEL assessments can provide meaningful data about students’ social and emotional skills that teachers can use to inform classroom instruction. Educators need sufficient time and training to understand the measurement tool and how it relates to the school’s SEL implementation framework before being asked to use and respond to data.

Implications for Policy

- States can include the knowledge and skills teachers need to support students’ SEL in state teaching standards. Including a strong focus on SEL in teacher licensing and accreditation standards could help bring coherence to how SEL is included in the scope and sequence of preservice coursework and create the expectation that all teachers need to meet these standards.

- States and institutes of higher education can adopt performance assessments that require teacher candidates to demonstrate SEL-focused skills and knowledge as a condition of teacher licensure. For example, California’s new Teaching Performance Expectations, along with its video-based performance assessment, include specific standards regarding SEL, culturally responsive teaching, and the ability to provide a socially and emotionally safe learning environment that must be met for licensure. States could add to or supplement their current assessments of teacher candidates to ensure that candidates demonstrate the skills needed to support students’ SEL.

- Policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels can invest in university-district partnerships that strengthen teacher candidates’ field experiences and enhance districts’ ability to support students’ SEL. Student teaching experiences are at the heart of preservice programs, so it is critical that teacher candidates have strong mentor teachers who effectively address the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning. States and districts, as well as institutions of higher education, can incentivize these partnerships through funding and technical assistance.

- Federal, state, and local efforts can support school and district leaders’ learning about SEL and administrators’ role in supporting teachers and students. Principal and district leadership is essential to sustaining a focus on SEL, and high-quality principal development requires financial investment. States can use federal funds to offset the expense of principal preparation and training. States may want to consider taking advantage of targeted funds, such as those provided in Title II of the Every Student Succeeds Act, to make strategic investments in their school leader workforce.

- Policymakers can also provide schools with resources and technical assistance as they seek to advance SEL. Educators need to be trained to analyze schools’ needs and implement high-quality programs, professional development, and school organizational changes that support students’ development. Lakewood Elementary and Sunnyvale School District are fortunate to have professional development support from multiple sources, but not all schools and districts know where to turn. Federal- or state-level support may include technical assistance, the facilitation of peer learning networks, and funding to bolster schools’ efforts in supporting students’ SEL.

- States and districts can provide well-validated tools to measure SEL, school climate, and related school supports. Well-designed and well-implemented measurement tools can help educators make strategic decisions about investments in student services and programs, ranging from measures of school climate and students’ social and emotional competencies to diagnostic measures such as protocols for observing and reflecting on educator practices and school structures. Staff surveys can strengthen educators’ voice in their professional development and allow them to weigh in on which supports they need most.

Preparing Teachers to Support Social and Emotional Learning: A Case Study of San Jose State University and Lakewood Elementary School by Hanna Melnick and Lorea Martinez is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

We are grateful to the Stuart Foundation for its support of this work, to the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation and the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative for their additional support in this area, and to the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation for their core operating support of the Learning Policy Institute.