Essential Building Blocks for State School Finance Systems and Promising State Practices

Summary

The report upon which this brief is based provides essential guidance to policymakers and advocates who write school finance laws to ensure a more equitable and efficient school finance system centered on student need. We begin with a discussion of the two critical foundational steps for developing a high-quality, equitable school finance system. We next address the essential building blocks for designing that system, which are grounded in legitimate and necessary costs reflecting meaningful student learning and opportunity. Finally, we end with a brief overview of three states that stand out as examples for creating more equitable, high-quality school finance systems.

Introduction

In statehouses across the United States, debates renew each year about how best to fund public education. While there are many different approaches to school funding systems, to achieve strong outcomes, there are key foundational steps and essential building blocks needed to ensure that every student has equitable access to meaningful educational opportunities.

Foundational Steps for Creating a Strong, Equitable School Finance System

Step 1: Set Standards and Goals for High-Quality and Equitable Education

The art of creating a strong, equitable school finance system that provides an excellent education for all students is no easy task, but neither is it beyond reach. The first step in creating a strong, sustainable school finance system is the development of high standards and goals for public education that ensure a high-quality, equitable education for all students.

Equity in this context refers to two important principles. First, equity refers to the consideration of legitimate and necessary educational opportunities tied to specific learning needs of all schoolchildren. Second, in the more traditional sense, equity concerns the distribution of resources equitably among school districts, irrespective of arbitrary factors such as property wealth. States can measure levels of equity through various frameworks, including equity of inputs, equity of outcomes, and equity of opportunity to achieve a specific level of outcomes.

Step 2: Identify Steady, Adequate Revenue Streams for Instruction and Operations

The next step is to identify steady and adequate revenue streams to support instructional costs, operational costs, and capital costs. In most states, local governments pay for nearly half of the education budget, primarily through local property taxes. This creates an inequitable base, because tax bases vary substantially. State funds are allocated to equalize district capacity. Because several taxes are susceptible to volatile economic activities, a good rule of thumb is to have a mix of taxes that are more stable and help offset any inherent inequities between school communities. These can include personal and corporate income taxes, sales taxes, business franchise taxes, motor vehicle and gasoline taxes, tobacco and alcohol taxes, lottery proceeds, and mineral taxes.

Once these foundational steps are in place, there are several essential building blocks, supported by specific policies and practices, that are needed to create an equitable and adequate school funding system.

Essential Building Blocks for School Finance Systems

Regular Program Allotment

The regular program allotment (also known as the basic, or foundation, allotment) makes up the bulk of education funding. In theory, it aims to cover all the standard costs for education needed to meet established state goals for student learning. (These are sometimes determined through cost studies.) In reality, these amounts are often set according to the prior year’s appropriations and politicking, bearing little relationship to the actual costs of educating students to meet the standards or costs reflective of best practices identified in the field.

Estimating the costs for the regular program can be difficult because of the many personnel, programs, and services involved, but there are critical learning opportunities that must be considered. Chief among these key considerations are educator salaries and benefits that allow schools to recruit, hire, and retain high-quality, effective teachers and school leaders. States should seek to ensure teacher salaries are competitive with those of other college graduates so that they can attract and retain a high-quality teaching force. Other essential teacher supports that can improve student learning include strong preparation, mentoring, and professional development programs. These investments increase effectiveness and reduce turnover, saving significant money that must otherwise be spent on the results of student failures and the costs of teacher replacements.

Curriculum materials and equipment needed to teach the standard curriculum must be considered as well. States need to take into account the needs of different students (for example, those in poverty, English learner [EL] students, and students with disabilities). In addition, states can create greater opportunity and equity for high-need, rural, and small-size school districts by adjusting their regular program allotment by other legitimate factors affecting costs, including regional cost indices, adjustments that account for school size and sparsity, and inflationary factors.

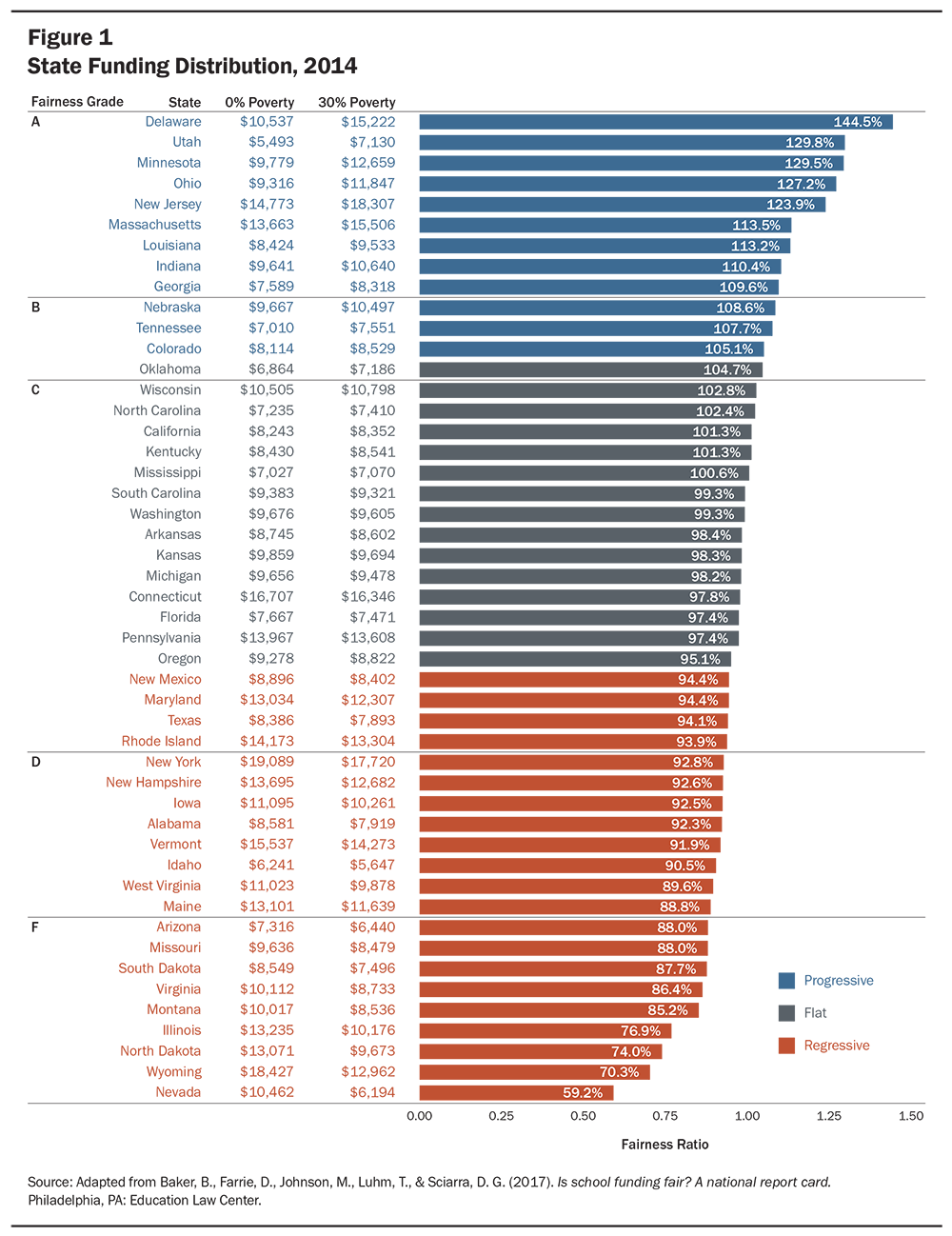

As Figure 1 shows, states differ considerably in their level of funding, including the extent to which it is sufficient to cover the costs of meeting the state’s standards and the extent to which their allocations are progressive; that is, the extent to which they allocate more to districts with a greater number of children in poverty.

Special Student Programming

As schools across the nation continue to diversify along race, language, and socioeconomic status, states must continue to adapt their school finance systems to meet children’s needs. Although the regular program allotment intends to reach the standard educational needs of every child, many children require additional or modified opportunities. These include students at risk of being retained or not graduating because of the circumstances in their underserved communities (e.g., those from low-income families), their personal characteristics (e.g., students with disabilities, EL students), or sometimes both (e.g., EL students who temporarily lack full English proficiency and reside in an underserved community). Collectively, these student groups are referred to as “high-need” students.

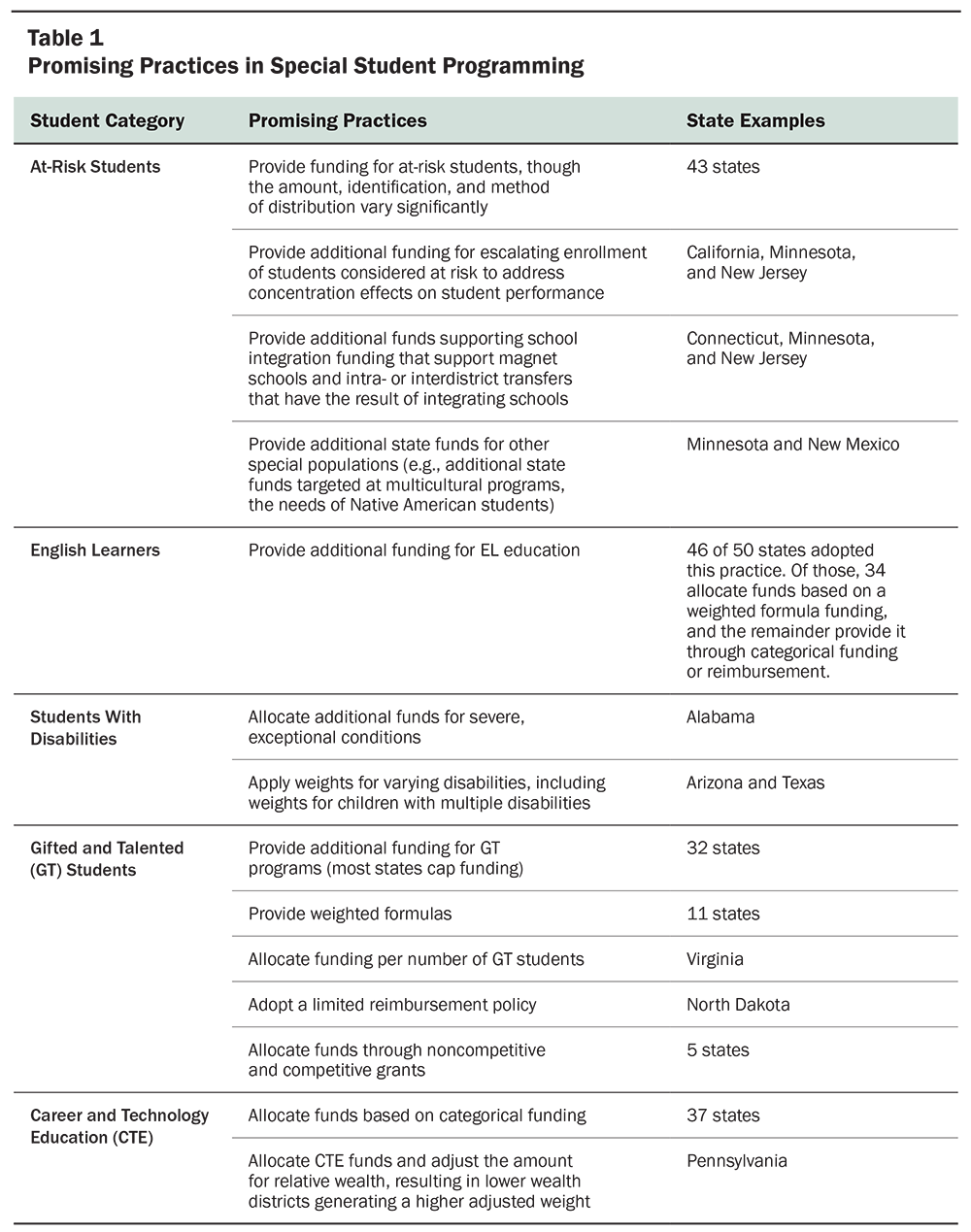

Approaches to funding student needs can include weighted student formulas, which increase the base foundation amount for each such student or increase the pupil count by a ratio meant to capture the additional costs of educating that child, such as a 1.5 count for each EL student (referred to as a weighted student count); categorical aid formulas, which add various amounts of additional funding beyond the basic formula; or reimbursement of costs within certain parameters (see Table 1). Typically, the weighted student formula approach is preferred because it allows the funding for high-need students to rise together with the foundation formula if it is increased.

Promising Practices: A growing number of states use a foundation allotment designed to allow students to achieve the state’s learning standards to collect and distribute funds to public school districts. The foundation formula itself does not resolve equity problems. What also matters is the amount collected and whether it is disbursed equitably, taking the educational needs of students into account.

Massachusetts, which is among the states with the highest allotments after adjusting for regional differences, developed a “foundation budget” based, in part, on actual costs. It is derived by multiplying the number of students at each school level, adjusting those enrollment figures by type of student (e.g., EL student, vocational education student), multiplying those numbers by various education spending categories (e.g., teacher compensation, professional development, building maintenance), and then adding together those amounts to arrive at the foundation budget. The formula also includes additional funding for students from low-income families and special education students. After Massachusetts adopted this formula in the early 1990s, several studies found that the new funding scheme helped raise achievement and reduce achievement gaps by race and income.

High-Quality Pre-K

Pre-k continues to grow in popularity across the country, with enrollment in state-funded programs doubling between 2000 and 2013. Access, quality, and funding, however, remain significant challenges nationally. Eighty-three percent of 4-year-old children in the highest wealth quintile attend preschool, compared to only about 50% in the lowest quintile. And while research shows promising returns in terms of high-quality pre-k programs closing achievement and high school attainment gaps between underserved students and others, many states have failed to invest in high-quality pre-k.

Promising Practices: New Jersey has a well-funded, high-quality pre-k program, which—in combination with its highly equitable foundation formula, provides parity funding to low-wealth districts and additional funding for students with particular needs. New Jersey’s pre-k funding has helped raise achievement and reduce the achievement gap. Combining state and federal Head Start program funding, New Jersey’s full-day pre-k program serves all at-risk 3- and 4-year-old students.

Oklahoma, too, has enacted universal full-day pre-k and, like New Jersey, combines funding from the state with funding from Head Start programs. Alabama’s evolving pre-k program is also worthy of note. The state’s pre-k program met all the quality benchmarks set by the National Institute for Early Childhood Education Research in 2017, and state funding increased by 33% between 2015–16 and 2016–17, from $48.5 million to $64.5 million, which will increase the percentage of Alabama 4-year-olds enrolled from 20% to 25%.

Facilities

The condition of school facilities has been correlated to school climate, student achievement, absenteeism, and teacher retention. Yet, because most states rely on local property taxes, facilities funding typically reflects even greater inequities between high-wealth and low-wealth school communities than instructional and operational costs.

Promising Practices: Some states assume larger shares of construction costs, such as Rhode Island (78%), Massachusetts (67%), Wyoming (63%), and Connecticut (57%). States can increase the equity and sufficiency of facilities funding by ensuring the maintenance of a stable funding source specifically for facilities and protecting against economic impacts by setting an annual minimum spending amount. In addition, states can ease debt financing by allowing school districts to use the state’s credit rating and providing greater debt assistance to lower wealth communities. Wyoming is one of the lowest debt states for school systems, because it provides funding for facilities on the front end, thus requiring local communities to rely only minimally on long-term bonds.

Transportation

Transportation costs vary widely between and within states. Factors impacting transportation include the number of students per square mile, age of transportation vehicles, location of schools, and presence of dangerous road crossings. Of the 46 states providing transportation funds, a majority (24) use some method of reimbursement, with only three states allowing for full cost reimbursement. Transportation could be included in the regular program allotment, but only if actual costs are adequately considered.

Promising Practices: Nine states provide transportation funding through their formulas. Very recently, the Massachusetts state auditor called for the state to fully fund its commitment to reimburse 100% of regional school district transportation costs in an effort to modernize its laws and structure.

Technology

Technology requires purchases and maintenance of infrastructure, hardware, and software. Teachers also must be trained on how to best integrate technology into instruction. State policymakers must be cognizant of the lack of technology capital and professional development funds in underserved communities.

Promising Practices: States often provide one-time grants to address technology needs, but these assume that technology needs do not accumulate over time. Although one-time grants can address specific needs, funds are also needed to support ongoing technology demands. Maine provides laptops to students and developed a revenue stream that continues to provide technology funds annually. An annual student-based technology allotment better equips schools to support and expand the use of technology.

Equalized Local Enrichment and Innovation

Several states typically allow school districts to access additional funds for enrichment and innovation beyond the regular program allotment. Those funds typically lie outside the equalized systems, thereby creating less efficiency because revenue is outside the system and less equity because wealthier districts have much greater access. In addition, the line is typically blurred between what is part of the regular program and what is enrichment, such as electives and extracurricular activities. Accordingly, if such funds are made available, states should ensure that all communities have equitable access to those funds.

Additional Steps for Creating a Strong, Equitable School Finance System

Creating a strong, equitable school finance system is a daunting task. However, it is attainable if efforts focus on student need and meaningful educational opportunities. Establishing a strong foundation and developing the building blocks are only the first steps in creating a high-quality, equitable school finance system. The remaining steps include

- estimating costs using research-based methods;

- fully implementing the plan and distributing the funds;

- monitoring expenditures, opportunities, and outcomes;

- and periodically reviewing the system with a broad group of inclusive stakeholders to ensure the goals of education and equity are being met.

Additionally, the school finance system is only part of creating great schools for every child. As the Intercultural Development Research Association lays out in its research-based Quality Schools Action Framework, there are other important levers of change, including change strategies, school system indicators, and outcome indicators that must be considered alongside to ensure every child has the best opportunity to succeed in school and in life. This comprehensive, student-need approach is necessary to deliver the promise of public education.

Essential Building Blocks for State School Finance Systems and Promising State Practices (policy brief) by David Hinojosa is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this document, and the series of reports as a whole, was provided by the Raikes Foundation, along with the general operating support from the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation.