How States Are Expanding Quality Summer Learning Opportunities

Summary

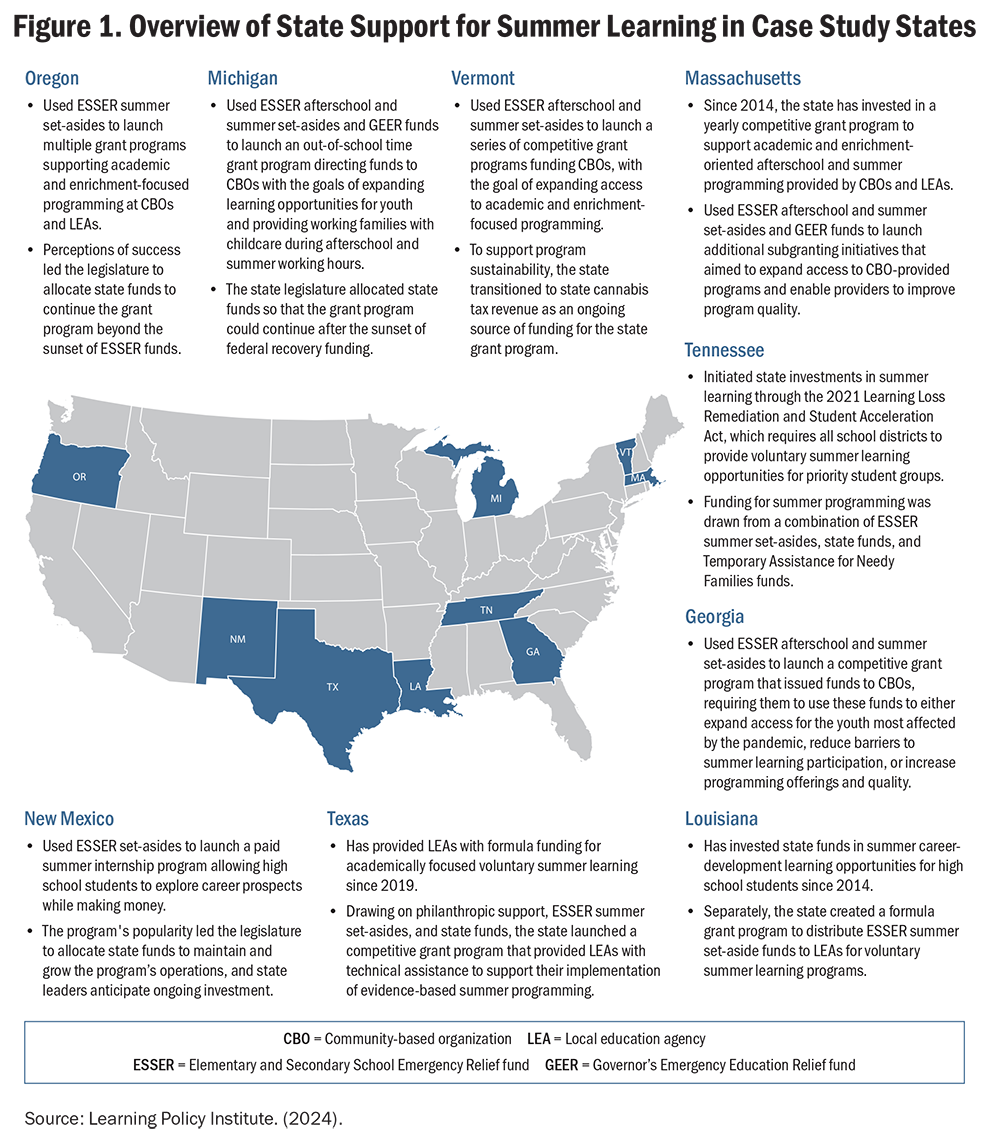

As federal funding for summer learning as a pandemic recovery strategy phases out, state governments face decisions about their future role in supporting students’ access to quality summer learning opportunities. This brief summarizes findings from nine geographically and politically diverse states—Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Mexico, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont—that have adopted different approaches to state-level summer learning investments. The findings highlight the following key strategies: (1) garnering support for investment by articulating clear goals, developing coalitions to generate political will, and identifying sustainable funding sources for summer learning; (2) implementing competitive grant programs that minimize administrative burden for applicants and grantees, allow for implementational flexibility, and are administered in partnership with nongovernmental entities; (3) directing investments toward increasing access for student groups that stand to benefit most from summer learning investments; (4) promoting high-quality implementation either through grant requirements, voluntary quality guidance, and/or technical assistance; and (5) collecting and using data to evaluate quality and improve implementation.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

State Support for Summer Learning

In the United States, summer marks a departure from the resources and support that are available to students and their parents during the school year.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25546 Students’ different experiences during the summer months contribute to the opportunity gaps and achievement gaps that exist between students from families with low incomes and those from families with higher incomes.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25546 By making summer learning programming more accessible, states can not only mitigate these gaps but also build on student strengths, nurture developmentally positive relationships, and address students’ academic and wellness needs (see Promoting High-Quality Programming for information on markers of quality in out-of-school time).Learning Policy Institute. (2022). Whole child policy toolkit. https://www.wholechildpolicy.org/rkdl-page/full/Whole-Child-Policy-Toolkit.pdf; McCombs, J. S., Augustine, C. H., Unlu, F., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Naftel, S., Gomez, C. J., Marsh, T., Akinniranye, G., & Todd, I. (2019). Investing in successful summer programs: A review of evidence under the Every Student Succeeds Act. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/t/RR2836

States have always played a role in supporting summer learning, most commonly through their administration of federal program funding that can be used for summer programs (e.g., Title I and 21st Century Community Learning Centers).Augustine, C. H., & Thompson, L. E. (2020). Getting support for summer learning. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/t/RR2347 In some cases, states have stepped further into their support role by allocating additional state funding for academic or enrichment programs. For the most part, however, state funding for summer has been limited, and decision-making about the types of programs and services that districts offer during the summer months has, historically, been the purview of local education agencies (LEAs).

There is reason to believe that, going forward, many states may decide to take on a larger role in the summer learning sector. As part of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding package, the federal government required all states to set aside a minimum of 1% of state ESSER funds to provide evidence-based summer learning programs. This stipulation drew unprecedented state attention to summer learning as a strategy for addressing pandemic-era learning disruptions and prompted many states to build new or expand existing infrastructures to distribute financial resources to summer learning providers—the LEAs and community-based organizations (CBOs) that host summer programs—and guide their implementation of programming. As a result, states helped to create opportunities for academic acceleration, enrichment, and career exploration that have benefited hundreds of thousands of students and working families across the country.

As ESSER funding sunsets, states face decisions about their future role in supporting students’ access to quality summer learning opportunities. Given the evidence that well-implemented and well-attended academic, enrichment, and employment-oriented summer programs can effectively support students’ academic learning, social development, and emotional well-being,McCombs, J. S., Augustine, C. H., Unlu, F., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Naftel, S., Gomez, C. J., Marsh, T., Akinniranye, G., & Todd, I. (2019). Investing in successful summer programs: A review of evidence under the Every Student Succeeds Act. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/t/RR2836 there are good reasons for states to continue their involvement in this area.

Through case studies of nine geographically and politically diverse states—Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Mexico, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont—we examined a variety of approaches to state-level summer learning investment with the goal of understanding the policies and practices that states have developed to expand access to high-quality summer learning programs. In this brief, we describe how states went about garnering support for summer learning investments, implementing state summer learning grant programs, creating access for priority student groups, promoting high-quality programming, and collecting and using data.

Garnering Support for Summer Learning Investments

The availability of federal recovery funds for summer learning, along with a pressing need to address students’ academic recovery, social connectedness, and well-being, went a long way toward building buy-in for summer learning during the pandemic recovery years. However, as states move forward, maintaining a focus on and resources for summer learning may require significant political will, planning, and leadership.

Participants from the case study states identified strategic approaches that helped to solidify support for summer learning investment in their states. First, the practice of articulating clear goals for summer learning investments and linking these goals with broader state priorities helped summer learning advocates communicate to other state actors how summer investments could complement other policy objectives, both in education and across sectors. For example, in New Mexico, support for a paid summer internship program gained traction because it would provide high school students with career development opportunities. This type of program was viewed as having the potential to reduce high school drop-out rates by helping students understand the workforce value of their high school learning and their future diplomas. Across states, common goals for summer programs included advancing students’ academic achievement; enriching students’ academic learning and social development; building students’ career-related skills and prospects; and supporting working families.

State leaders played an important role in establishing a vision for how summer learning investments could accomplish these goals and leveraged their positions and relationships to generate momentum for state investment. For example, the Vermont governor used his public platform to commit the state to providing “universal” access to afterschool and summer learning opportunities for all Vermont students. He called on legislators to develop a plan to achieve this goal, resulting in the development of a legislative task force that ultimately drafted the framework for a statewide grant program.

In many cases, stakeholder coalitions that brought together summer learning advocates from state agencies and legislative bodies, philanthropic organizations, local government, and state afterschool networks played an important role in generating the political will that led to state investment. Well-organized coalitions allowed for information sharing, collaborative planning, and collective advocacy that were, in several states, essential in generating initial and ongoing investments in summer learning. As in the case of Michigan, states could sustain the involvement of these coalitions after summer learning investments were secured by giving stakeholders seats on advisory committees that would guide grant program implementation.

Finally, state advocates also worked to identify a consistent funding source for summer learning, beyond federal recovery funds. For instance, Massachusetts has sustained state investments in summer learning since 2014 by establishing a budget line item for the state summer learning grant program. In Texas, including summer learning funds as part of the school funding formula ensured access to ongoing funding for LEAs. States also had opportunities to claim emergent funding streams, such as cannabis tax revenue or legalized gambling revenue streams, to fund summer learning programs.

Implementing State Grant Programs for Summer Learning

To support summer learning, most states implemented formula or competitive grant programs that varied in their eligibility criteria and administration. These grant programs allocated funding to different types of organizations, depending on the state. Some states, notably those with greater focus on driving academic growth, channeled funding to LEAs to provide standards-aligned learning opportunities during the summer months. Other states designed grant programs that included CBOs—specifically, nonprofits that provide afterschool or summer learning programming—as eligible grantees, given their demonstrated ability to provide programming that promotes student well-being, develops life skills, and enriches academic learning.

In all cases, states aimed to develop grant programs that would make funds broadly accessible to summer learning providers. Accessibility was a notable concern in states that included CBOs as potential recipients of state funds, since these organizations tend to exhibit greater variety in terms of organizational capacity (including experience with grant writing and grant management) and the types of programming that they provide. With the goal of minimizing barriers to grant program uptake, states funding both CBOs and LEAs aimed to minimize the administrative burden associated with applying for grant funds (e.g., by simplifying application procedures and reporting requirements or, in the case of Texas, adopting a formula funding model for LEA summer learning providers). They also established grant requirements that allowed for flexibility, so that grant-funded providers could customize programming in accordance with their organizational capacity and their unique contexts.

Another notable implementation strategy was the use of partnerships to enhance often-limited capacity at state education agencies (SEAs). In several states, particularly in those that included CBOs as eligible grantees, the SEAs partnered with nongovernmental organizations to administer or support administration of their summer learning grant programs. State afterschool networks emerged as particularly important partners for case study states. These networks exist in all 50 states, and they have much to contribute, in terms of both their advocacy power and technical expertise, to state initiatives focused on summer learning. In Georgia, for example, the Georgia State Afterschool Network’s (GSAN) long-standing relationships with CBO providers enabled the organization to efficiently distribute grant funds and provide technical support. Partnering organizations like GSAN brought unique expertise, such as data collection and analysis, high-quality programming, and technical assistance. In several cases, partners leveraged pre-existing relationships with summer learning providers that informed grant design or facilitated the publicization of grant opportunities.

Increasing Access for Priority Groups

In many cases, states invested in summer learning with the goal of serving specific student groups, including students performing below grade level, students from specific grade levels, students needing additional educational services (e.g., students with an individualized education program or who are English learners) and students from underserved communities or low-income families.

States directed investments toward groups that stood to benefit most from summer learning investments by identifying priority groups in legislation or the grant’s request for proposals. For instance, states could give priority students “right of first refusal” for summer learning program seats (as in Tennessee) or give preference, when allocating grant funds, to providers who historically have served priority student groups, are located in high-poverty areas, or submit grant proposals indicating their intent to expand access for these student groups using grant funds. For example, Oregon ranked LEAs’ priority for grant funds based on the percentage of priority students they served, whereas Vermont prioritized providers who intended to use grant funds to expand access for underserved populations. In some cases, state requests for proposals communicated that they would give funding preference to providers that would use grant funds to address known obstacles to summer learning participation by, for example, decreasing program cost, providing transportation, or launching or expanding programs in rural areas where no or few summer learning options exist. States regularly analyzed grant-funded programs’ participation data to understand the extent to which state investments were benefiting priority student groups. Doing so helped to clarify ongoing gaps in accessibility, which states could then strategically address in future iterations of grant program design.

Promoting High-Quality Programming

In addition to expanding access to summer learning opportunities, states worked to promote the quality of funded programs (see Markers of Quality in Out-of-School Time Programming). One approach was to require elements of quality as a condition of funding—for instance, by issuing requirements around staff qualifications or program instructional materials. In Tennessee, for example, the Learning Loss Remediation and Student Acceleration Act requires that summer programs use high-quality and state-approved curricular materials and be taught by a licensed teacher who is certified to teach the subject.

Markers of Quality in Out-of-School Time Programming

Research on out-of-school time programming—which includes both summer and before- and after-school learning opportunities—points to specific program features that are associated with positive attendee outcomes. For programs focused on promoting the personal and social skills of youth, the following components stand out as important:

- well-trained staff who deliver instruction focused on building specific skills,

- active learning opportunities, and

- positive youth–staff interactions and site climate.

In addition to these, in academic-focused programs, the following components have been found to contribute to positive academic outcomes:

- sufficient program duration and student attendance,

- instruction from certified teachers with content and grade-level experience, and

- academically rigorous curriculum.

Sources: Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309; Schwartz, H. L., McCombs, J. S., Augustine, C. H., & Leschitz, J. T. (2018). Getting to work on summer learning: Recommended practices for success (2nd ed.). RAND Corporation.

However, many states were conscious that having too many programming requirements could deter providers from applying for state funds. With this in mind, some states chose to issue voluntary quality guidance that provided recommendations on best practices and, in the case of Louisiana, included template documents that programs could customize (e.g., sample schedules, data collection plans, and planning checklists and timelines). By issuing this guidance, states provided program providers with knowledge and tools that they could use to voluntarily improve the quality of their programming, as their program capacity allowed.

Some states provided services designed to promote program quality. A number of states provided technical assistance to funded providers, aiming to promote the design and implementation of high-quality programs and thereby increase the impact of the state investment. This was the case in Texas, where LEAs could apply to participate in a yearlong Planning and Execution Program that supported their implementation of evidence-based summer learning programs.

Taking a different tack, a limited number of states supported workforce development by offering training and professional development for summer program staff or helping providers connect with prospective hires in their areas. By doing so, states helped to cultivate a well-qualified summer learning workforce and connect providers with the staffing needed to implement high-quality programming.

Collecting and Using Data

Data collection and analysis can help state agencies and stakeholders understand the impact of state investments relative to their vision and goals for summer learning. As noted, states in this study aimed to accomplish different things through investments in summer learning and, in many cases, their data collection and usage plans reflected these varying priorities. States collected data for many purposes but most commonly to understand program participation, ongoing unmet demand for summer programming, the program content offered by funded providers, and the academic impact of summer learning participation. The data used for these purposes came from numerous sources, which varied by state but included end-of-year grant reports, provider and participant surveys, interviews and focus groups, site visits, and standardized assessment and evaluation tools.

States then mobilized this data toward a number of different ends. They used it to evaluate provider quality and identify implementation strengths and challenges of state grant programs. In both cases, the broader purpose was to inform data-driven continuous improvement processes, with the goal of improving the quality of providers’ programming and/or the effectiveness of state grant programs. Furthermore, states mobilized program data to advocate for ongoing state investment, either by highlighting positive outcomes from funded programs or by illustrating the ongoing need for quality summer opportunities. This was the case in New Mexico, where stories and survey data from participating youth helped make the case to legislators that the state should grow and sustain the program with state funds.

Several state leaders noted the tension between a desire for standardized and detailed reporting requirements and the administrative burden that these requirements can impose on providers, potentially deterring them from pursuing state funding. To address this challenge, several states in this study designed grant programs to minimize the reporting burden on providers. One strategy was to use a subgranting process for grant dissemination, which allowed the intermediary grantee, typically an organization with greater capacity, to shoulder most reporting requirements on behalf of the subgrantee summer learning provider. Another strategy was to allow providers to use their existing data collection tools to report program outcomes, rather than having them adopt a new, standardized tool. Additionally, to support providers with limited capacity to collect and report high-quality data, states provided technical assistance and training on the usage of common quality assessment tools.

Conclusion

When students have access to well-implemented summer learning programs, they have the opportunity to improve academic achievement, socialize with peers and trusted adults, and cultivate their emotional and physical well-being during the summer months. These summer experiences matter for addressing opportunity gaps and achievement gaps that exist between students from families with low incomes and those from families with higher incomes.

With the goal of broadening students’ and families’ access to quality summer opportunities, some states, including those whose state-level investments have been analyzed in this brief, have begun to embrace a larger role in relation to summer learning. By investing in summer learning, either through grant programs or via formula funding structures, states provided resources that enabled providers to increase their enrollment capacity, improve program quality, and decrease program cost or otherwise promote access for priority student groups.

In many states, the full potential of the summer months remains untapped. By investing in summer learning, states can better support the developmental and academic needs of students over the course of the full year—not just during the months when school is in session.

How States Are Expanding Quality Summer Learning Opportunities (brief) by Julie Fitz, Julie Woods, Naomi Duran, and Jennifer McCombs is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by The Wallace Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages.