Teacher Shortages in California: Status, Sources, and Potential Solutions

Summary

Teacher shortages have been worsening in California since 2015. Growth in teacher demand as the economy has improved has collided with steep declines in the supply of new teachers, leading to significant increases in the hiring of underprepared teachers, especially in districts serving high-need students. Shortages are most severe in special education, mathematics, and science, and are growing in bilingual education; these are also areas where teacher attrition is high. This brief reviews a set of evidence-based policies the state could consider to build a lasting supply of well-prepared teachers.

About Getting Down to Facts II

California’s education system has seen substantial policy shifts over the past decade potentially benefiting the state’s 6.2 million students. Getting Down to Facts II (GDTF II) is an in-depth research report that serves as a “state of the state,” with the goal of providing a common set of facts to inform discussions and education policy development going forward. Learn more >

California’s teacher shortages are serious and have been getting steadily worse over the last few years. After years of budget cuts and layoffs, the 2014–15 school year brought an upturn in the economy, along with a voter-approved funding initiative (Proposition 30), and historic school finance reform (the Local Control Funding Formula). These enabled school districts to begin rebounding from the Great Recession; many reinstated classes and programs that had been cut during years of dwindling budgets and teacher layoffs. As districts posted new job openings, they discovered that qualified teachers were now hard to find. Since then, the shortage has deepened. In response, the state has invested nearly $200 million over the last several years to recruit, prepare, support, and retain teachers.

Will these programs be enough to mitigate the problem? And what else may be needed to staff the state’s classrooms? To help provide answers, the Learning Policy Institute conducted an analysis of the California teacher workforce to determine the dimensions of, causes of, and potential solutions to the shortage.

Key Findings

- The shortfalls result in part from steep declines in the production of new teachers and sharp increases in demand as districts seek to replace staff let go in the years of cutbacks.

- Teacher shortages, while widespread, are more pronounced in certain subject areas—mathematics, science, special education, and bilingual education—and in schools with larger percentages of high-need students.

- Schools have dramatically increased their hiring of teachers with sub-standard credentials who have not completed, or often even started, preparing to teach.

In this brief, we summarize our report that details these findings, outlining trends in teacher supply, declines in teacher education enrollment, increases in demand, and the role of attrition. The brief looks at strategies for addressing shortages and concludes with policy considerations.

Trends in Teacher Supply

Stagnant teacher supply is insufficient to meet demand

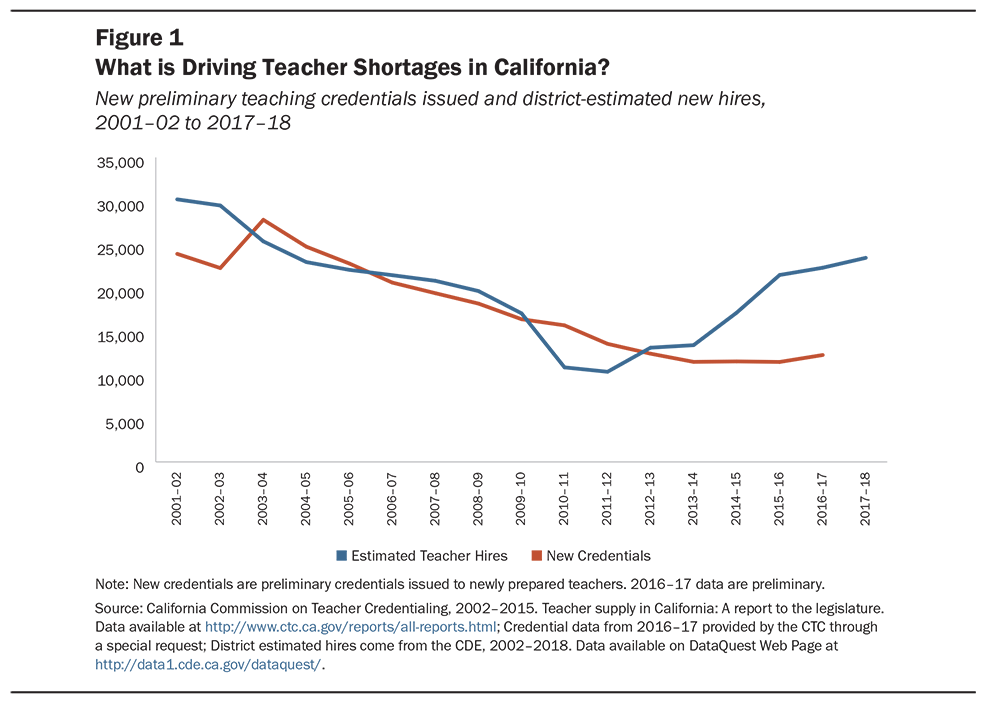

Between 2002 and 2016, as budgets were increasingly tight and hiring was slow, the supply of new teacher candidates declined by more than half (see Figure 1). The number of new teaching credentials issued annually to fully prepared candidates remains near historic lows at roughly 12,000, and not all of these recipients enter the profession in California. Some leave for other states, and others pursue other activities. Even though California has attracted nearly 4,000 additional teachers from out of state and close to 8,000 re-entrants to the profession, supply is not keeping pace with demand. While districts have, in the aggregate, estimated their annual demand for the coming year at about 24,000 annually, their actual hiring has exceeded these estimates, reaching nearly 30,000 in recent years (see Figure 1).

As a result, since 2014–15, California districts have reported acute teacher shortages, especially in mathematics, science, and special education.Darling-Hammond, L., Furger, R., Shields, P. M., & Sutcher, L. (2016). Addressing California’s emerging teacher shortage: An analysis of sources and solutions. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Podolsky, A., & Sutcher, L. (2016). California teacher shortages: A persistent problem. (Brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Addressing California’s growing teacher shortage: 2017 update. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. In a fall 2016 survey of 211 representative school districts, 75% reported shortages of qualified teachers for that school year, and about one third reported shortages even in traditional areas of surplus, such as elementary education, English, and social studies.Podolsky, A., & Sutcher, L. (2016). California teacher shortages: A persistent problem. (Brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. A year later, in a fall 2017 survey of districts representing a quarter of the state’s enrollment, 80% reported a shortage for 2017–18. Of respondents to the 2017 survey, 90% said the shortages were as bad or worse than the previous year.Sutcher, L., Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Understaffed and underprepared: California districts report ongoing teacher shortages. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

When districts cannot fill a position with a qualified teacher, they have few good options. California districts have hired long-term substitutes or teachers with substandard credentials, left positions vacant, increased class sizes, or canceled courses—all of which can undermine instructional quality and student achievement.On the impact of substitute teachers: Damle, Ranjana. (2009). Investigating the impact of substitute teachers on student achievement: A review of the literature. (Brief). Albuquerque: Albuquerque Public Schools. Accessed 11/16/15, ; Miller, R. T., Murnane, R. J., & Willett, J. B. (2008). Do teacher absences impact student achievement? Longitudinal evidence from one urban school district. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 30(2), 181–200; Brown, S. L., & Arnell, A. T. (2012). Measuring the effect teacher absenteeism has on student achievement at a “urban but not too urban” Title I elementary school. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(17), 172–183; On the impact of teachers who are not fully prepared: Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Lankford, H., Loeb, S. & Wyckoff, J. (2006). How changes in entry requirements alter the teacher workforce and affect student achievement. Education Finance and Policy, 1(2), 176–216; Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D. J., Gatlin, S. J., & Vasquez Heilig, J. (2005). Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Evidence about Teacher Certification, Teach for America, and Teacher Effectiveness. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(42); Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). Teacher credentials and student achievement: Longitudinal analysis with student fixed effects. Economics of Education Review, 26(6), 673–682. On the impact of vacancies that lead to late hiring: Papay, J. P., & Kraft, M. A. (2015). Delayed Teacher Hiring and Student Achievement: Missed Opportunities in the Labor Market or Temporary Disruptions? Unpublished manuscript; On the impact of class size and larger classes due to course cancelation: Glass, G. V., & Smith, M. (1979). Meta-Analysis of class size and achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 1(1), 2–16; Mosteller, F. (1995). The Tennessee study of class size in the early school grades. The Future of Children, 5(2), 113–127; Nye, B., Hedges, L. V., & Konstantopoulos, S. (1999). The long-term effects of small classes: A five-year follow-up of the Tennessee class-size experiment. Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 21(2), 127–142; Kim, J. (2006/2007). The relative influence of research on class-size policy. Brookings Papers on Education Policy, 273–295. Deeply worrisome is the impact on the future: teacher shortages now threaten the state’s hard-won new education initiatives related to more challenging standards, curriculum, instruction, and assessments—all designed to move the system toward more meaningful 21st century learning.

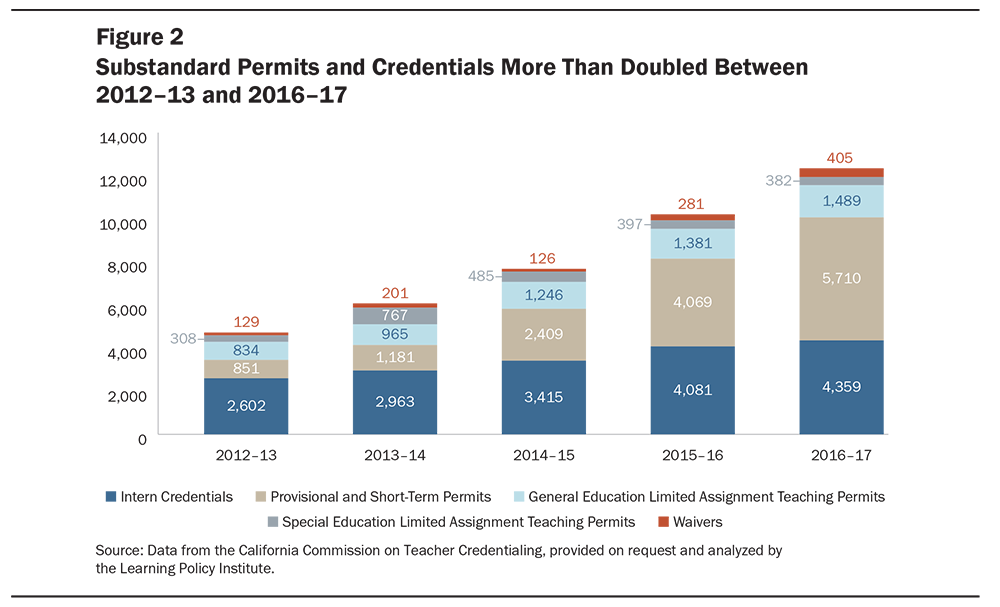

The supply-demand mismatch has led to significant increases in substandard credentials

In 2016–17, California issued more than 12,000 intern credentials, permits, and waivers, more than double the number issued in 2012–13 and roughly half of all authorizations issued this past academic year. The greatest growth has been in emergency-style permits, which numbered close to 6,000 in 2016-17 (see Figure 2). These are granted only when there are “acute shortages” to individuals who have demonstrated neither that they are competent in the subject area they are teaching, nor that they have entered a program to prepare them to teach.

Shortages are more pronounced in certain subject areas and schools

Shortages are most severe in special education, where 2 out of 3 new teachers now enter on substandard credentials, and in mathematics and science, where about half of new teachers are entering without preparation. In all of these fields, the number of new teachers issued full credentials has declined steadily over the last 5 years, while the number entering on substandard credentials has increased. Shortages are also emerging in bilingual education since voters passed Proposition 58 in the fall of 2017, which reinstated such programs.

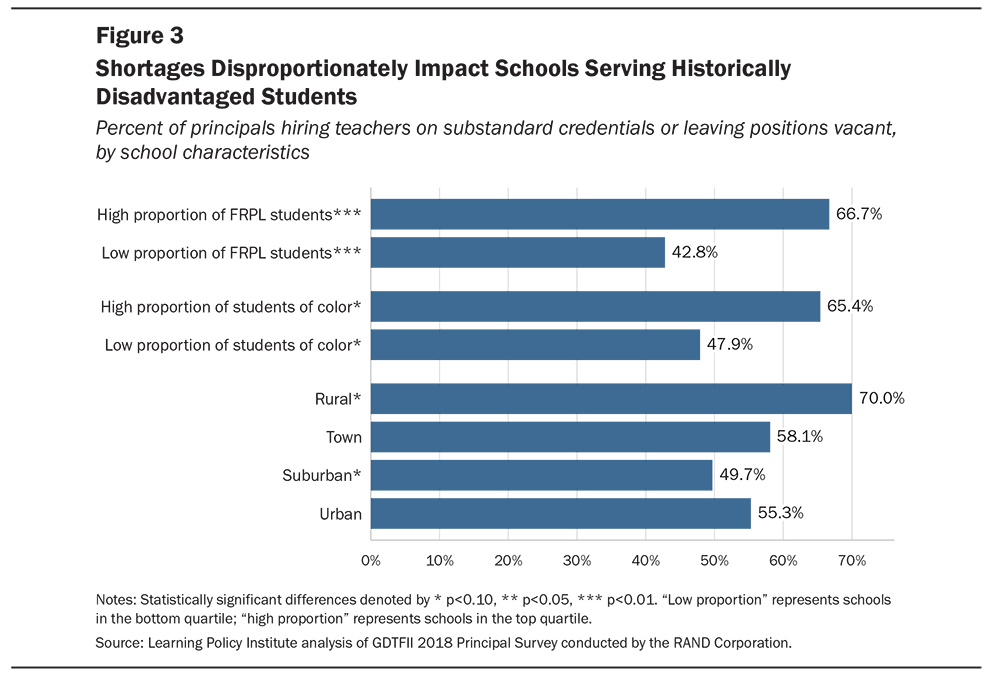

In high-need schools, shortages are more pronounced and extend to other subject areas, including English and elementary education. In a fall 2017 survey of California principals, two thirds of principals serving schools with high proportions of students of color and students from low-income families (in the top quartile) left positions vacant or hired teachers on substandard credentials, while fewer than half of their peers in schools with few students from low-income families or students of color did so.American School Leader Panel. (2017). GDTFII Survey. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. For this calculation, we compared principals in schools in the top quartile in California in terms of the proportion of free and reduced-priced lunch-eligible students to principals in schools in the bottom quartile. (see Figure 3).

Declines in Teacher Education Enrollments

A small uptick has followed a steep decline in new entrants to teaching

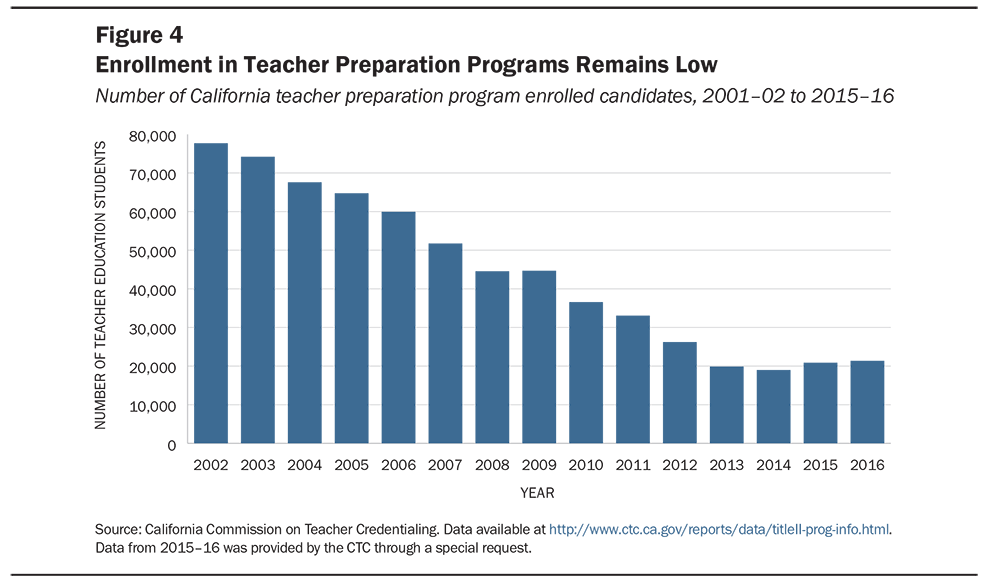

A 70% decline over the last decade in teacher education enrollments is reversing slightly, but the small recent increase in completers has stalled in the UC/CSU system, which typically provides about 60% of California’s newly credentialed teachers each year (see Figure 4).

Although the system theoretically has capacity to grow, restrictions on program enrollments caused by CSU rules that typically tie slots to the previous year’s enrollments may be slowing many programs’ ability to respond to the growth in demand. Other factors that influence the supply of qualified teachers include:

- candidates’ need for financial aid, identified by both teacher education program directors and school district leaders as a major factor limiting teacher supply; and

- relatively low admittance rates for university programs from among the pool of candidates who apply, as program leaders note a shortage of qualified applicants. Candidates must meet California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) requirements to pass tests of basic skills and subject matter knowledge, in most cases prior to admissions, plus tests of reading and teaching performance prior to licensure. Failure rates on the overall set of tests eliminate at least 40% of individuals who start the process of becoming a teacher, and more than 50% in mathematics and science, where pass rates are particularly low, even for candidates who have majored in these fields of study.

Increases in Demand

Demand has increased as districts seek to reduce high pupil-teacher ratios

The number of annual teacher hires has hovered around 30,000 since 2014–15, a 30% increase over the demand for new hires in 2012–13, the year before school funding began to improve. In 2014–15, about 25% of this new demand was driven by reductions in the pupil-teacher ratio; that share has since dropped to about 12%. Overall, the average pupil-teacher ratio has fallen from 23:1 to 21:1, which is nearly pre-recession levels but still one of the highest in the country. (The national average is 16:1.) Whether this source of demand continues will depend in part on resources available to schools in the coming years.

Enrollments are projected to remain stable and then decrease slightly over the next decade if current birthrates and immigration trends continue. Increases or decreases will vary in different parts of the state, but for most districts, enrollment growth will not be a major driver of demand.

The Role of Teacher Attrition

Teacher demand is driven largely by attrition

In recent years, the lion’s share (88%) of teacher demand has been driven by attrition. About 8.5% of teachers leave the profession or state each year, and another 8% go to teach at another school. About two thirds of attrition tends to be pre-retirement, but since 34% of teachers statewide are age 50 and older, retirements will continue to be an important factor in some locations over the next decade.

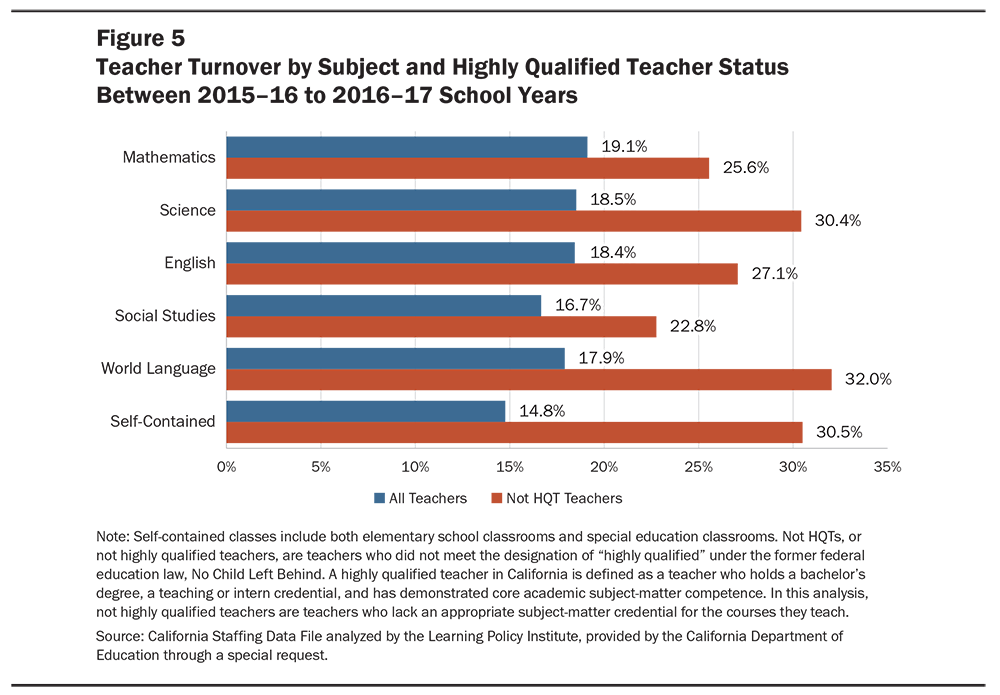

Turnover rates are higher in certain subject areas and schools

In California, mathematics, science, and English teachers turn over at higher rates than teachers in other fields (see Figure 5). Currently available data do not allow us to separately identify all special education or bilingual teachers: those in self-contained classes (shown in Figure 5) can include many of these teachers as well as most elementary teachers. Nationally, special education and bilingual education teachers also turn over at higher rates. In addition, underprepared teachers are much more likely to leave: Those designated as not “highly qualified teachers” (HQT) under federal law (which in California means teachers on emergency credentials or assigned out of field) are nearly twice as likely to leave in each subject area. For teachers who are not highly qualified and work in self-contained classrooms—most of whom are in special education (since few elementary teachers enter on emergency credentials)—the proportion leaving is 30.5%, more than twice the turnover rate for qualified teachers.

Teachers in Title I schools and in schools serving high proportions of students from low-income families and students of color all have higher rates of teacher churn. Moreover, schools in rural, town, and urban communities all have higher turnover rates than schools in suburban areas. African American teachers have higher turnover rates than Latinx, White, and Filipino teachers.

Job satisfaction, working conditions, compensation, and preparation affect turnover

A 2017 survey found that California teachers are generally satisfied with their jobs overall, although those who teach in more challenging contexts are somewhat less satisfied. However, most teachers report being concerned about the status of and respect for the teaching profession. Relatedly, research shows that compensation (including salaries, college debt levels, and housing costs) matters to teachers’ career decisions, as do working conditions—especially having a supportive administrator and a collegial work environment.

Turnover for beginners is influenced by levels of preparation and early mentoring. Teachers without preparation before entry leave teaching at 2 to 3 times the rate of fully prepared teachers, and those without mentoring leave teaching at about twice the rate of those who receive regular mentoring, collaborative planning time with other teachers, and a reduced teaching load.

Strategies to Date for Addressing Shortages

Over the last 4 years, California has worked to curb teacher shortages by investing nearly $200 million in programs to recruit and retain teachers by helping classified staff become certified, starting new undergraduate programs for teacher education, and supporting training for bilingual teachers. In summer 2018, the state made its largest investment to date in two additional programs—one supporting teacher residencies to recruit and train teachers in special education, mathematics, science, and bilingual education ($75 million); the other supporting local solutions to special education teacher recruitment and retention ($50 million).

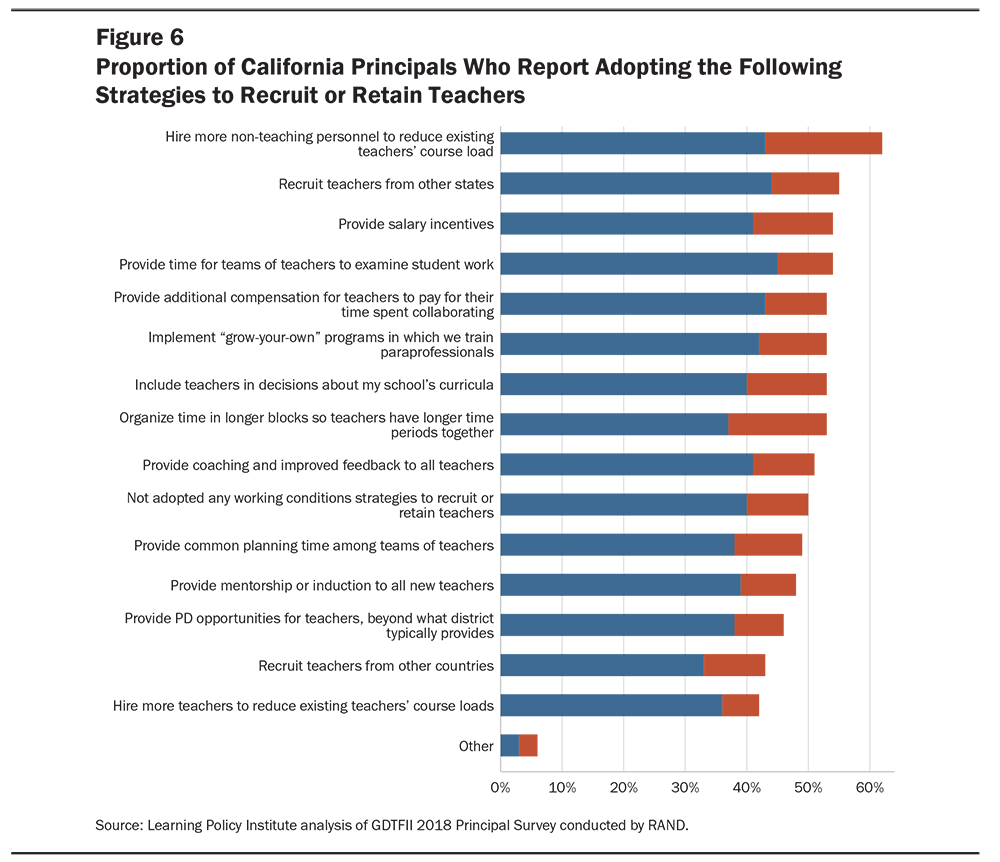

Meanwhile, local leaders have been pursuing their own solutions. In the earlier-mentioned 2017 principals’ survey, more than half of principals reported seeking to hire more non-teaching and teaching personnel to lighten existing teaching loads, recruiting and retaining teachers by way of Grow Your Own programs, recruiting teachers from other states and countries, and providing salary incentives for all teachers or those in shortage areas (see Figure 6).

Many leaders are also seeking to improve teaching conditions by providing time for teaching teams to plan and examine student work; creating more collaboration time and longer blocks of time for teachers to work together; and by involving teachers in decision making, mentoring, coaching, and professional development. In some cases, these efforts are specific to teachers in shortage fields, but most often they pertain to all teachers.

Policy Considerations

Much of California’s teacher shortfall appears to be the result of steep declines in the production of new teachers as demand has increased; however, recruiting more teachers will not be enough to solve the shortages if attrition remains at high levels. Since attrition accounts for nearly 90% of annual demand, a key policy strategy is to expand the pathways to teaching that hold the greatest potential to both recruit and retain teachers. Previous research suggests consideration of the following evidence-based approaches:

- Loan forgiveness programs and service scholarships. Teachers currently earn about 30% less than other college graduates.OECD. (2017). Education at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris, FR: Author. As a result, some who would like to teach eschew the profession because they do not think their salaries will offset their college debts. A 2017 survey of California teacher preparation programs administered by the CTC found that faculty were most likely to identify lack of financial aid for teaching candidates as the largest obstacle to increasing enrollment in their programs, and a 2017 survey of district officials found that service scholarships were also their number one recommendation for addressing teacher shortages.

Loan forgiveness programs and service scholarships have been found to be highly effective in recruiting individuals into teaching and directing them to the highest need fields and locations.Podolsky, A. & Kini, T. (2016). How effective are loan forgiveness and service scholarships for recruiting teachers? Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. These programs can be structured to underwrite preparation in exchange for a number of years of service in the profession—usually in high-need locations and subject areas. Examples of such programs include the now-defunct Assumption Program of Loans for Education (APLE) loan forgiveness program and the Governor’s Teaching Fellowship that provided teacher candidates with between $11,000 and $20,000 in exchange for a commitment to teach for at least 4 years in high-need schools and subjects. Beneficiaries of those programs were more likely to teach in low-performing schools and had higher retention rates than the state average.Steele, J. L., Murnane, R. J., & Willett, J. B. (2010). Do financial incentives help low-performing schools attract and keep academically talented teachers? Evidence from California. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(3), 451–78; Podolsky, A. & Kini, T. (2016). How Effective Are Loan Forgiveness and Service Scholarships for Recruiting Teachers? (policy brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. - Teacher residencies. One-year intensive apprenticeships modeled on medical residencies have consistently resulted in higher teacher retention rates. Targeting high-need subjects and locations, they also have been found to attract more diverse candidates, thus supplying a diverse pool of effective teachers for high-need fields.Guha, R., Hyler, M.E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Residents apprentice alongside an expert teacher in a high-need classroom for a full academic year while completing coursework for a master’s degree at a partnering university. They typically receive a stipend and tuition assistance in exchange for a commitment to teach in the district for 3 to 4 post-residency years. California has about a dozen such programs across the state.Learning Policy Institute. (2016). Teacher Residencies in California (policy brief). Palo Alto, CA: Author. As previously noted, the legislature recently appropriated $75 million for teacher residencies focused on special education, mathematics, science, and bilingual education teachers. Designing and implementing these well will be a critically important next step for the state.

- Grow Your Own programs. Such programs recruit, train, and support paraprofessionals, after-school program staff, and other local community members to teach in their own communities. The California Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program, funded with $45 million in 2016 and 2017, is supporting up to 2,250 classified staff, such as teachers’ aides, to earn a bachelor’s degree and teaching credential. The program provides classified staff with $4,000 per year for up to 5 years to subsidize their teacher training costs. Nearly half of program participants are Hispanic or Latinx, and 5% are African American. Districts submitted grant applications for more than 8,000 slots, suggesting significant unmet need that can be addressed by continuing the program in upcoming years.California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2017, December). Report to the Legislature on the California Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program.

- Support and mentoring programs for novice teachers. High-quality induction that includes one-on-one mentoring is associated with higher teacher retention rates and improved student learning.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. All beginning California teachers are required to complete an induction program to earn their clear credential. However, state funding once targeted for induction is now folded into the Local Control Funding Formula. This has resulted in many districts reducing their support for new teachers, providing support in the second instead of first year, charging new teachers a fee for induction, or requiring new teachers to enroll at an institution of higher education to complete induction. To address this problem, the state needs to renew the quality and availability of its longstanding Beginning Teacher Support and Assessment Program.

- Removal of unnecessary barriers to entry. California has taken some steps to remove barriers to entry by easing rules for license reciprocity for teachers from other states and enabling candidates to substitute adequate scores from other academic tests for the basic skills (CBEST) exam. But more can be done. Fully prepared candidates seeking to transfer in from other states still sometimes have to jump through unnecessary hoops, even when they are highly experienced.

CTC testing policies also pose significant barriers to credentialing. While professions such as law and medicine require one test after completion of training (e.g., the bar exam or medical licensing exam), the CTC requires four tests for most multiple-subject teaching candidates and three for most single-subject candidates. Only one of these—the teacher performance assessment taken at the end of candidates’ training—has been shown to be related to later teaching effectiveness. Besides raising financial and logistical hurdles, these tests have significant fail rates. At least 40% of all those who initially intend to teach—and more than half in mathematics and science—are waylaid by testing. The CTC is already examining coursework-based pathways for some requirements (e.g., demonstrating subject-matter competence through programs of study) and should be encouraged to look further at these issues. - Utilization of retirees. California could follow the example of many other states and utilize retirees to help address shortages—especially since 10% of the teacher workforce is over age 60 and nearing retirement. Some states have expanded the pool of qualified educators by recruiting retirees to serve in shortage areas or to mentor beginning teachers. Such states typically eliminate barriers to re-entry, such as mandatory separation-from-service periods and caps on earnings that may apply while a teacher is receiving a pension—two barriers currently in effect in California. If teachers contribute to the retirement fund while they are working, even if they draw down retirement income, the approach can be cost-neutral.

- Investments in teacher preparation and training. The state may need to expand program availability in fields such as special education, where annual demand is extremely high and where a number of programs were earlier closed down. Because licensing expectations for such teachers are changing, the state could issue competitive grants to support the design of new program models. There may also be a need to evaluate the university funding rules that determine how quickly teacher education program enrollments can be expanded within the CSU system. This may involve targeting some state CSU funds specifically for teacher education or changing university rules that constrain annual growth in teacher education slots on some campuses.

- Investments in principal preparation and training. Comprehensive strategies to address teacher shortages should consider the central role principals play in attracting and retaining talented teachers. Teachers cite principal support as one of the most important factors in their decisions to stay in a school or in the profession, especially in high-poverty schools.Goodpaster, K. P. S., Adedokun, O. A., & Weaver, G. C. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions of rural STEM teaching: Implications for rural teacher retention. Rural Educator, 33, 9–22; Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2011). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 303–333; Marinell, W. H., & Coca, V. M. (2013). Who stays and who leaves? Findings from a three-part study of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools. New York, NY: Research Alliance for New York Schools. Research demonstrates that a principal’s ability to create positive working conditions and a collaborative, supportive learning environment plays a critical role in attracting and retaining qualified teachers.Hughes, A. L., Matt, J. J., & O’Reilly, F. L. (2015). Principal support is imperative to the retention of teachers in hard-to-staff schools. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 3(1), 129–134; Brown, K. M., & Wynn, S. R. (2009). Finding, supporting, and keeping: The role of the principal in teacher retention issues. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(1), 37–63; Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552–2585. With the transition to ESSA—including new opportunities in the law to set aside up to 3% of Title II funds to support leadership development—a growing number of states are committing resources to strengthen school leadership in ways that can support efforts to recruit and retain high-quality educators.Espinoza, D. & Cardichon, J. (2017). Investing in effective school leadership: How states are taking advantage of opportunities under ESSA. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. California’s State Board has suggested it will likely seek to do this—a move that should be designed to focus training on issues of teacher support.

- Improvements in teaching conditions. Many states create incentives for improving teaching conditions by using school-by-school working conditions surveys to provide ongoing data on teachers’ experiences and perceptions. Conditions can be improved through investments in collaboration time, professional learning communities, pupil load reductions (especially important for special education teachers in California at the moment), and career ladders that compensate teachers who gain expertise and use it to mentor and coach other teachers. One example of a previously successful California strategy is the state’s now defunct Teachers as a Priority program, which provided funding to high-need schools so they could improve conditions ranging from mentoring to class sizes to collaboration time.

- Availability of data. Finally, to manage supply and demand more effectively, there is an immediate need to support greater availability and analysis of teacher-related data. These data can reveal entry and exit patterns for teachers of different subjects and training backgrounds and show the productivity—in terms of recruitment and retention—of different pathways and investments in teaching. Such analysis requires the use of the merged data sets at CTC and CDE, which are currently not analyzed for these purposes or made available to researchers.

Conclusion

A common objection to teacher shortage interventions is the belief that the teacher labor market will adjust on its own to meet demand. It is true that teacher supply is dynamic and adjusts as economic and social conditions change. As the demand for teachers increases, districts typically seek to improve salaries and working conditions where they can. If state funding continues to improve, and more individuals take an interest in teaching, a change will likely occur incrementally over the next few years. Nonetheless, shortages remain a major problem. The possibility of more teachers tomorrow does nothing to help students today. Even if teacher supply eventually adjusts to meet growing demand, that change could be years in the future. In the meantime, proactive policies are necessary so that the state’s most vulnerable students do not bear the cost.

Teacher Shortages in California: Status, Sources, and Potential Solutions by Linda Darling-Hammond, Leib Sutcher, and Desiree Carver-Thomas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The report was prepared in part for inclusion in the California Getting Down to Facts II Project and benefited from the ideas and feedback of its research team.

The Learning Policy Institute’s research in this area of work is funded in part by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for LPI is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.