California’s English Learners and Their Long-Term Learning Outcomes

Summary

California’s K–12 funding and instructional policies for English learners (ELs) have changed significantly over the past 2 decades, including new requirements for instructional materials specific to ELs statewide and a new school funding system that funds ELs at a higher rate. These major policy shifts held the potential to change student learning outcome patterns for ELs. This brief summarizes those policy changes and, as a first step in identifying their impact, describes changes over time in the development of academic skills and English proficiency among ELs in California. We find that English learners’ academic achievement by 3rd grade has improved over time, shrinking the achievement gaps between K-cohort ELs and other students in English language arts (ELA) and math. We also find that more-recent cohorts of kindergarten ELs are reaching English proficiency on the California English Language Development Test (CELDT) in earlier grades than previous cohorts did. For the less recent cohorts who had reached Grade 5 by 2018–19, we find almost no change in the overall share who were proficient in English by the end of elementary school. We also find only half of kindergarten ELs were reclassified as English proficient by the end of elementary school in 2018–19.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

More than 1 in 8 students in the United States are educated in California’s public school system. More than 40% of California students speak a language other than English at home, with most of these students classified as English learners (ELs) upon school entry and provided EL services, such as targeted English language development instruction.California Department of Education. (2024). Facts about English learners in California.

California has engaged in significant efforts to serve this population of students. Over the past 2 decades, California has changed its Teaching Performance Expectations to incorporate EL instruction (beginning in 2004), required instructional materials specific to ELs statewide (2004), instituted the Common Core State Standards for math and English language arts (2010) and a new English Language Development Framework (2012), overhauled its school funding system to fund ELs at a higher rate (2013), and reinstituted bilingual programming (2016). These major policy shifts had the potential to change student learning outcome patterns for ELs.

As a first step in understanding the impact of these policy changes, the study covered in this brief provides a descriptive analysis of trends in key outcomes across successive cohorts of English learners who started kindergarten in California during the years 2006–07 to 2018–19. To understand progress for a stable group of students, the analysis looks at these students in their “Kindergarten EL” cohort group over time even as many are reclassified as English proficient. The K-cohort EL students are then compared to same-cohort students who were never ELs. This kind of analysis tells us more about schools’ contributions to students’ English acquisition and long-term academic performance than simply looking at the federally defined “English learner” group, which changes every year as new immigrant students join the group and students who become proficient in English are taken out of the group.

Using data provided by the California Department of Education, the study follows the first of these cohorts through their potential graduation year from high school and follows eight cohorts through the usual end of elementary school (Grade 5). More-recent cohorts can only be followed through the earlier elementary grades. The study examined demographic changes, trends in academic outcomes, trends in timing to English proficiency, and timing to reclassification to shine a light on the backgrounds and academic trajectories of these students.

The California Policy Context

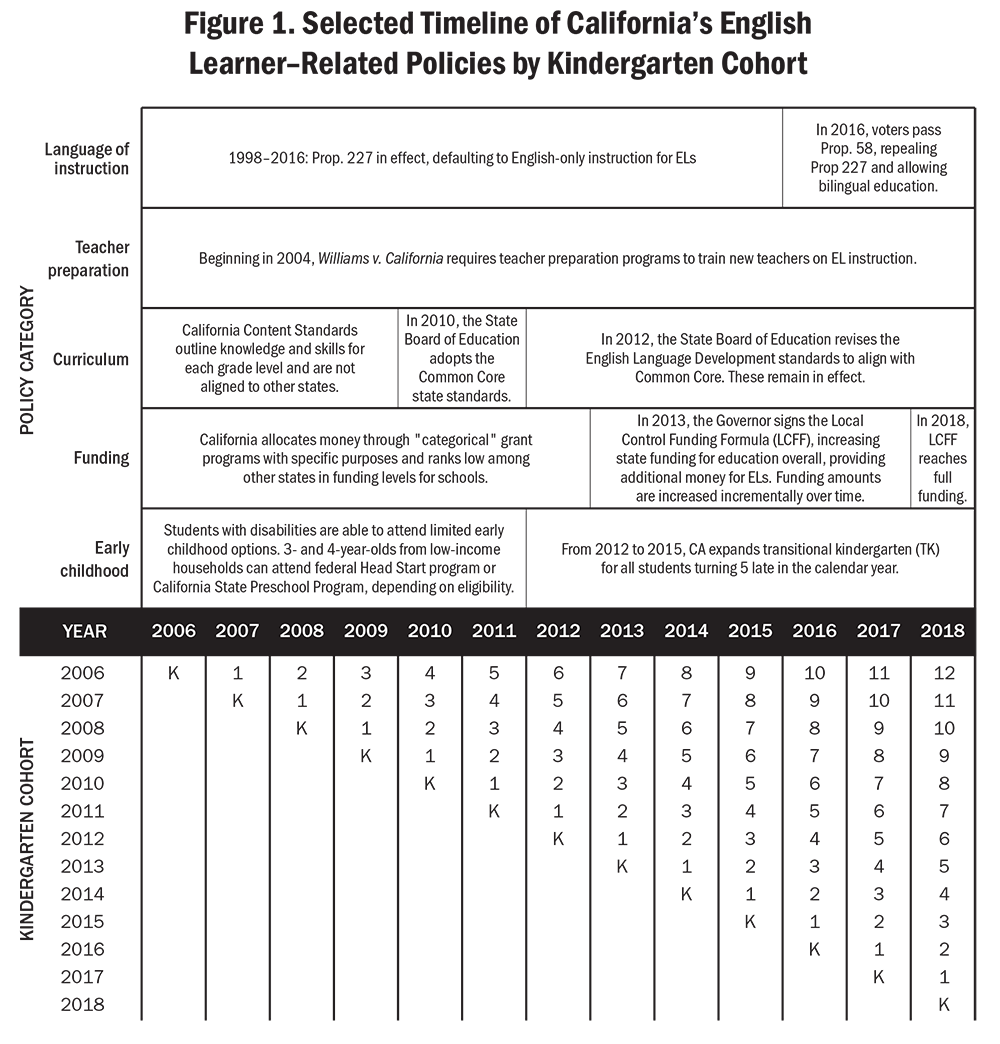

During the period of this study, 2006 to 2019, a wide-ranging set of new state policies was enacted, some of which directly contradicted previous policies. This policy landscape is depicted as a timeline in Figure 1, which shows when California introduced new regulations around teacher preparation, curriculum, school funding, early learning opportunities, and language of instruction for ELs.

Beginning in 1999, all teacher preparation programs statewide were required to incorporate lessons on EL instruction; however, that provision only covered new teachers. In 2004, the settlement of Williams v. California extended the requirement, mandating that all teachers acquire training and specific authorization to teach ELs. These changes were implemented based on research showing that teachers of ELs need to:

- be able to implement EL-specific scaffolds;

- possess EL-specific teacher expertise (such as linguistics); and

- ensure an EL-specific equity orientation with respect to cultural, ethnic, and linguistic diversity to help their students succeed.

Nine years after Williams v. California, the American Civil Liberties Union shared in a 2013 report that “Williams is working,” pointing to large reductions in the number of teachers instructing ELs without the certification to do so.Chung, S. (2013). Williams v. California: Lessons from nine years of implementation. ACLU Foundation of Southern California.

California also reformed its curricular standards during this time. In 2010, the California State Board of Education adopted the Common Core State Standards and began promoting them in professional development sessions with teachers and administrators. Two years later, the state revised its English language development standards to align with the Common Core; 2 years after that, California produced a joint English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework to guide instruction—the first curricular guidance in the nation that integrated English language development with English language arts. In 2015, the state implemented new standardized testing that also aligned with these goals, including the Common Core’s more complex academic literacy targets requiring attention to listening, writing, and research, as well as reading.

English learners also faced a new school funding environment in California during this time. The 2004 settlement of Williams v. California required adequate instructional materials specifically for ELs and ensured regular facilities assessments for adequacy. Then, in 2013, the passage of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) directed large amounts of money toward the education of ELs and gave local education agencies broad authority and greater discretion in how to spend the increased funding, while also stipulating that districts regularly consult with communities when making spending decisions. LCFF committed $18 billion in increased state support and distributed it on the basis of pupil needs (which is defined in part by the proportion of students in the district who are English learners), then incrementally distributed funds starting in 2015. The formula was fully funded earlier than expected, in the 2018–19 school year.

Early analyses of district-level spending plans showed that after LCFF, which required attention to ELs in districts’ Local Control and Accountability Plans, districts increased their focus on English language development courses and dual-immersion programs, both of which could have driven an increase in EL performance.Contreras, F., & Fujimoto, M. O. (2019). College readiness for English language learners (ELLs) in California: Assessing equity for ELLs under the Local Control Funding Formula. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(2), 209–225. Johnson found positive and significant effects of LCFF-induced increases in per-pupil spending on academic achievement for every grade assessed (3rd–8th and 11th), in both math and reading, for every school that experienced this new infusion of state funds, as well as for the kindergarten EL subgroup.Johnson, R. (2023). School funding effectiveness: Evidence from California’s Local Control Funding Formula. Learning Policy Institute.

There were also major expansions of public prekindergarten (PreK), which may have important implications for enriching early learning opportunities for ELs. Beginning in the 2012–13 school year, every elementary or unified school district was required to offer transitional kindergarten (TK) for eligible children who turned 5 late in the calendar year. These expansions of public PreK investments in education have been sustained over the past decade, with TK eligibility set to expand to include all 4-year-olds in future years. The expansion of TK and preschool may represent an important policy opportunity to narrow school readiness gaps.Johnson, R. C. (2024, May). Synergistic impacts of expansions in pre-k access and school funding on student achievement: Evidence from California’s transitional kindergarten rollout. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 114, 467–473. Amid growing evidence that school resource equity and funding adequacy matter for educational achievement and socioeconomic success in adulthoodBaker, B. D. (2018). How money matters for schools [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute. and early evidence on the successes of TK implementation in California,Johnson, R. (2023). School funding effectiveness: Evidence from California’s Local Control Funding Formula. Learning Policy Institute; Johnson, R. C. (2024). Synergistic impacts of expansions in pre-k access and school funding on student achievement: Evidence from California’s transitional kindergarten rollout. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 114, 467–473. we would expect to see improvements in EL performance due to these investments.

Finally, in 2016, California voters passed Proposition 58, which repealed the 1998 Proposition 227 and allowed schools throughout the state to establish bilingual education programs. Though districts were not required to create bilingual education programs, they were encouraged to do so. They were required to meet with community members to discuss the programs and offer bilingual programming if enough parents requested it.

Findings

Over the period of the study, kindergarten ELs became increasingly diverse linguistically, with the share of Spanish speakers decreasing from 84% to 77% over the period and speakers of Mandarin, Vietnamese, Cantonese, Korean, and Arabic increasing to represent another 10% combined, with many other languages spoken by the remainder of the student population. The share of kindergarten ELs who were socioeconomically disadvantaged also increased slightly over time (from 67% to 68%), with those in Spanish-speaking and the fast-growing Arabic-speaking groups most disproportionately from low-income households.

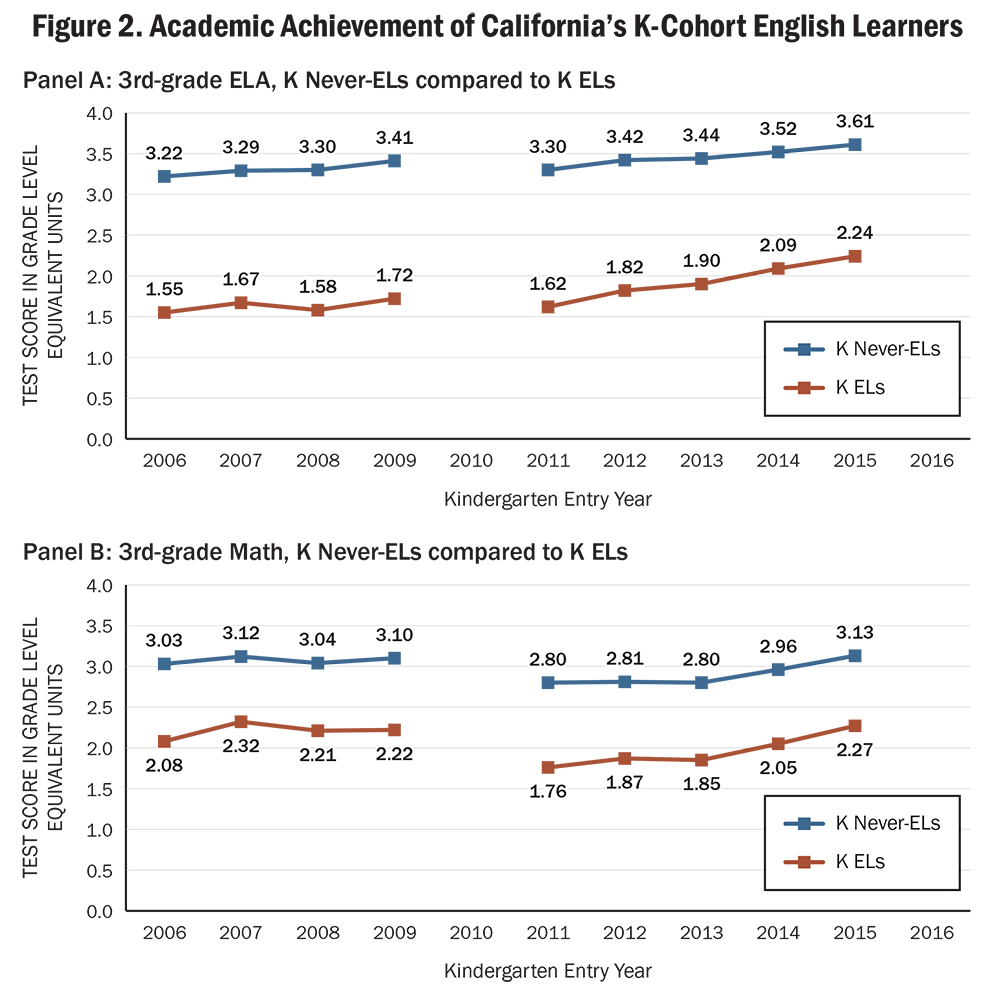

Despite the increase in low-income households, students’ academic achievement in 3rd grade improved over time, especially in the period from 2011 to 2016, shrinking the achievement gaps between K-cohort ELs and other students in ELA and math. (See Figure 2.)

Sources: California Department of Education data. Researcher calculations; Reardon, S., Kalogrides, D., & Ho, A. D. (2019). Validation methods for aggregate-level test scale linking: A case study mapping school district test score distributions to a common scale. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 46(2), 138–167.

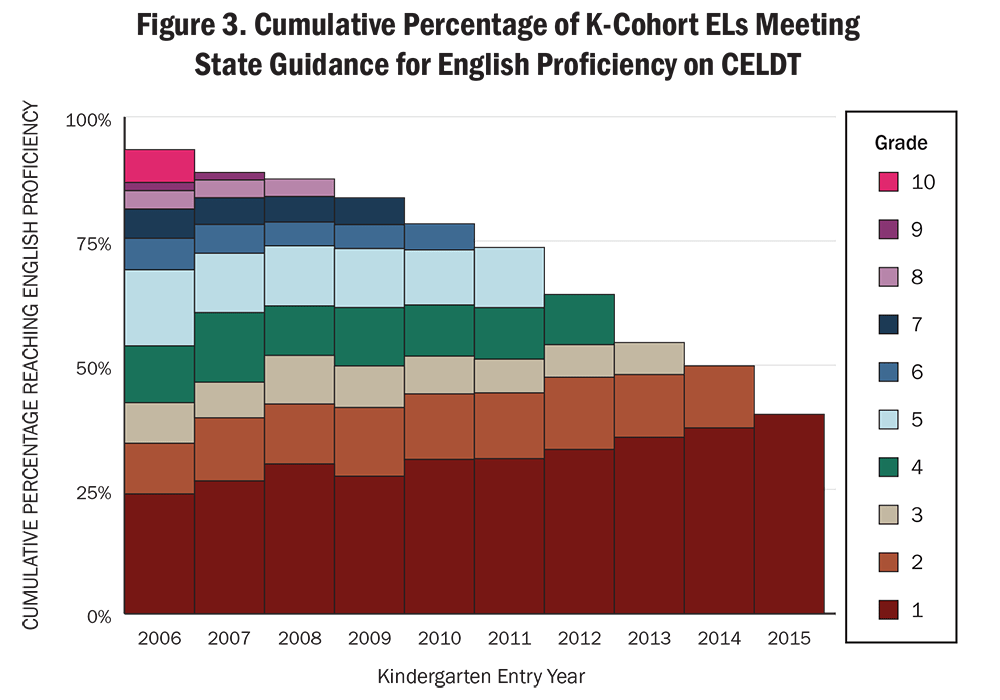

In addition, more-recent cohorts of kindergarten ELs reached English proficiency on the CELDT in earlier grades than previous cohorts. For example, whereas only 23% of EL students who entered kindergarten in 2006 had reached the English proficiency benchmark by the end of 1st grade, for those who entered kindergarten in 2015, the proportion who reached this benchmark by 1st grade was 40% (a two-thirds increase). For the older cohorts that we can observe through the end of 5th grade, proficiency acquisition by the end of elementary school did not change much. In 2006, our first class, 67.7% of K-cohort EL students reached Early Advanced on the CELDT by the end of 5th grade. For the kindergarten cohort of 2011, the most recent cohort that we can follow through the end of their elementary years, 72.2%—near three quarters—of kindergarten ELs reached Early Advanced on the CELDT by the end of 5th grade. (See Figure 3.)

Source: California Department of Education data. Researcher calculations.

Though rates of English proficiency acquisition and ELA test scores are improving, we do not observe comparable improvements in reclassification rates. Reclassification rates by the end of 5th grade were approximately steady between the kindergarten cohorts of 2008 and 2013. Furthermore, gaps remain between proficiency acquisition and reclassification. By the end of 5th grade, only 53% of ELs who started kindergarten in 2011 were reclassified, even though 72% had reached English language proficiency on the CELDT. In California, where English proficiency represents only one of the four criteria students must meet to be reclassified, this discrepancy demonstrates the role played by other barriers to reclassification, most likely the criterion to demonstrate basic skills on another assessment.

Conclusion

Taken together, these results show significant improvements in the academic trajectories of California’s ELs over time, likely due to improvements in the school learning environments that later cohorts of kindergarten ELs experienced. The results suggest that some combination of the policies described earlier—from more rigorous requirements for teacher preparedness for EL students to increased funding and the introduction of transitional kindergarten—has likely made a difference in EL outcomes. The patterns of improvement for academic achievement in ELA and math across successive cohorts of kindergarten ELs are aligned with the timing of initial LCFF implementation and the staggered rollout of increased funding between 2013 and 2018. Meanwhile, the reduction in time to English proficiency appears to be gradual, and steadily improves throughout the analysis period, suggesting a potentially positive role for the policies of the early 2000s, such as new regulations regarding teacher preparation and requirements for EL-specific materials in schools.

California’s English Learners and Their Long-Term Learning Outcomes (brief) by Sarah Novicoff, Sean F. Reardon, and Rucker C. Johnson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages.