Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence

Abstract

The report on which this brief is based synthesizes the research evidence about the impact of community schools on student and school outcomes. Its aim is to support and inform school, community, district, and state leaders as they consider, propose, or implement community schools as a strategy for providing equitable, high-quality education to all young people. We conclude that well-implemented community schools lead to improvement in student and school outcomes and contribute to meeting the educational needs of low-achieving students in high-poverty schools, and sufficient research exists to meet the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) standard for an evidence-based intervention.

Increasing economic inequality and residential segregation have triggered a resurgence of interest in community schools—a century-old approach to making schools places where children can learn and thrive, even in under-resourced and underserved neighborhoods. Community schools represent a place-based strategy in which schools partner with community agencies and allocate resources to provide an “integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, and community engagement.”Coalition for Community Schools. (n.d.). What is a community school? (accessed 04/08/17). Many operate on all-day and year-round schedules, and serve both children and adults.

Although this strategy is appropriate for students of all backgrounds, many community schools arise in neighborhoods where structural forces linked to racism and poverty shape the experiences of young people and erect barriers to learning and school success. These are communities where families have few resources to supplement what typical schools provide.

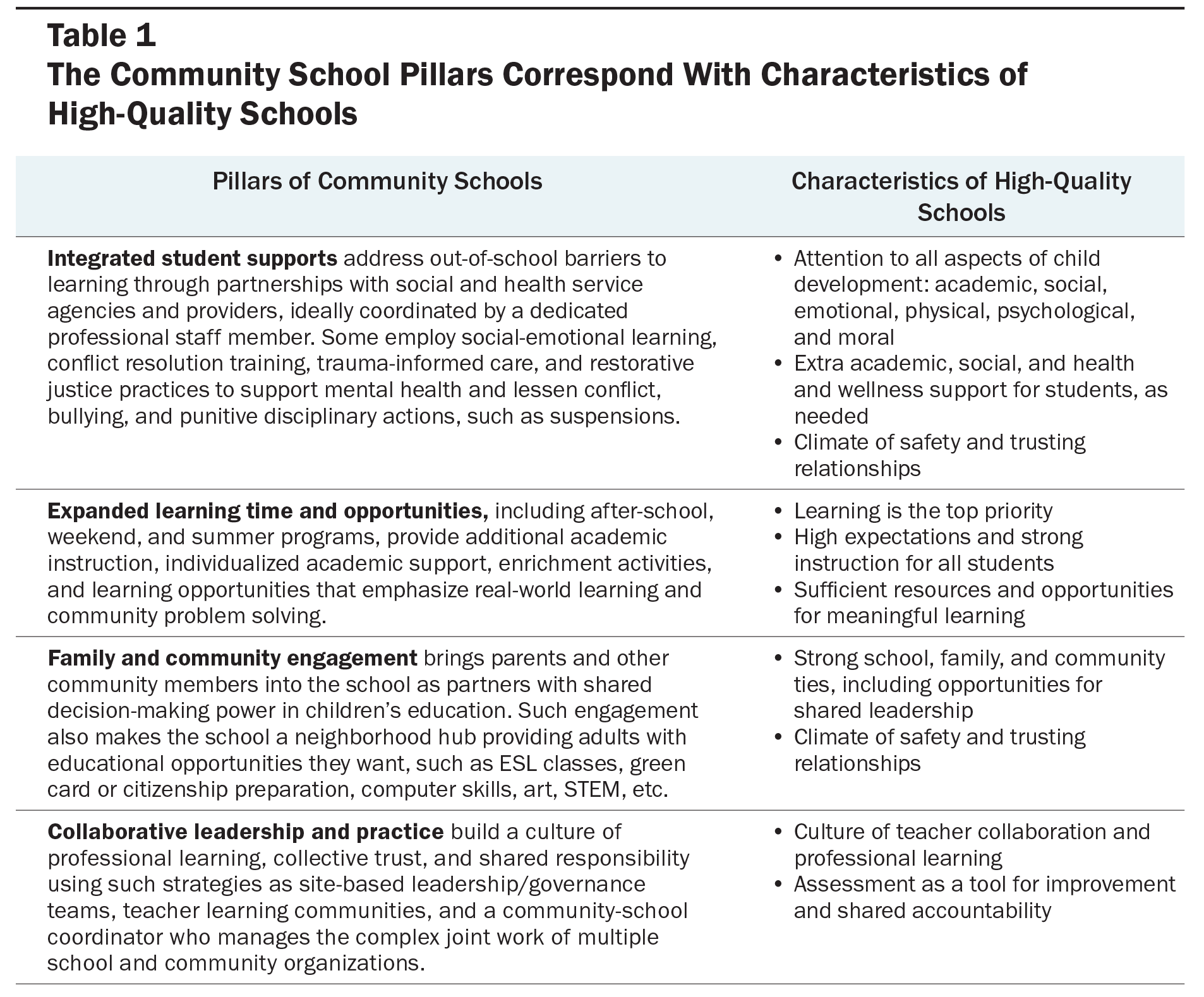

Community schools vary in the programs they offer and the ways they operate, depending on their local context. However, four features—or pillars—appear in most community schools, and support the conditions for teaching and learning found in high-quality schools (see Table 1).

- Integrated student supports

- Expanded learning time and opportunities

- Family and community engagement

- Collaborative leadership and practice

The report on which this brief is based examines 143 research studies on each of the four community school pillars, along with evaluation studies of community schools as a comprehensive strategy. In each area, the report synthesizes high-quality studies that use a range of research methods, drawing conclusions about the findings that warrant confidence while also pointing to areas in which the research inconclusive. In addition, we assess whether the research base justifies the use of well-designed community schools as an “evidence-based” intervention under ESSA in schools targeted for comprehensive support.

Oakland International High School: A Community School in Action

At Oakland International High School, approximately 29% of students—virtually all of whom are recent immigrants—arrived in the United States as unaccompanied minors. Some have lost family members to violence; some come to school hungry; some face risks simply getting to and from school. All are English learners and most live in poverty. Across the country, most students like them experience limited learning opportunities and barriers to success at school. But Oakland International students thrive at surprisingly high rates. Two thirds of those surveyed in 2015–16 said they are “happy at school,” compared with just over half of other Oakland high school students.

Careful internal tracking of the 5-year graduation rate for the class of 2015 shows a 72% success rate—high for this extremely vulnerable population. More than half of Oakland International’s 2014–15 graduating students (51%) took and passed the rigorous A–G courses required for admission to California state universities, compared with 24% of their English learner peers districtwide and 46% of all Oakland Unified School District students. In addition, college enrollment rates for Oakland International students reached 68% by 2014, outperforming the 2009 state average of 52% for English learners (the most recent statewide data available).

Why the difference? Oakland International is a community school. As such, it has an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth development, and family/community engagement. For example, it directly addresses the out-of-school barriers to learning faced by recently arrived immigrant students. Available supports include free legal representation to students facing deportation, after-school tutoring, English as a second language classes for parents, mental health and mentoring services at the school wellness center, medical services at a nearby high school health clinic, and an after-school and weekend sports program. Students also experience a rigorous academic program in which they create a portfolio of work, allowing them to develop advanced academic skills and demonstrate what they have learned in more meaningful ways than on a single test. Their work is graded with rubrics, and students have multiple opportunities for revision.

Findings

We conclude that well-implemented community schools lead to improvement in student and school outcomes and contribute to meeting the educational needs of low-achieving students in high-poverty schools. Ample evidence is available to inform and guide policymakers, educators, and advocates interested in advancing community schools, and sufficient research exists to meet the ESSA standard for an evidence-based intervention.

Specifically, our analyses produced 12 findings.

Finding 1. The evidence base on community schools and their pillars justifies the use of community schools as a school improvement strategy that helps children succeed academically and prepare for full and productive lives.

Finding 2. Sufficient evidence exists to qualify the community schools approach as an evidence-based intervention under ESSA (i.e., a program or intervention must have at least one well-designed study that fits into its four-tier definition of evidence).

Finding 3. The evidence base provides a strong warrant for using community schools to meet the needs of low-achieving students in high-poverty schools and to help close opportunity and achievement gaps for students from low-income families, students of color, English learners, and students with disabilities.

Finding 4. The four key pillars of community schools promote conditions and practices found in high-quality schools and address out-of-school barriers to learning.

Finding 5. The integrated student supports provided by community schools are associated with positive student outcomes. Young people receiving such supports, including counseling, medical care, dental services, and transportation assistance, often show significant improvements in attendance, behavior, social functioning, and academic achievement.

What Do Integrated Student Supports Look Like in Action?

Communities in Schools (CIS) is a national dropout prevention program overseeing 2,300 schools and serving 1.5 million students in 25 states. For nearly 40 years, CIS has advocated bringing local businesses, social service agencies, health care providers, parent and volunteer organizations, and other community resources inside the school to help address the underlying reasons why young people drop out.

Health screenings, tutoring, food, clothing, shelter, and services addressing other needs: CIS provides integrated student supports such as these by leveraging community-based resources in schools, where young people spend most of their day. Some integrated student supports benefit the entire school community, like clothing or school supply drives, career fairs, and health services, while more intensive supports are reserved for students who need them most.

CIS places a full-time site coordinator at each school; the site coordinator is typically a paid employee of the local CIS affiliate (a nonprofit entity governed by a board of directors and overseen by an executive director). Working with the CIS national office, state CIS offices provide training and technical assistance to local affiliates, procure funding through numerous sources, and offer additional supports that enable capacity building for site coordinators at the local level.

Source: Communities in Schools. (n.d.). About us (accessed 3/8/17); Bronstein, L. R., & Mason, S. E. (2016). School-linked services: Promoting equity for children, families and communities. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Finding 6. Thoughtfully designed expanded learning time and opportunities provided by community schools—such as longer school days and academically rich and engaging after-school, weekend, and summer programs—are associated with positive academic and non-academic outcomes, including improvements in student attendance, behavior, and academic achievement.

Finding 7. The meaningful family and community engagement found in community schools is associated with positive student outcomes, such as reduced absenteeism, improved academic outcomes, and student reports of more positive school climates. Additionally, this can increase trust among students, parents, and staff, which in turn has positive effects on student outcomes.

What Does Family and Community Engagement Look Like in Action?

Redwood City 2020 has transformed six of 16 schools in the Redwood City, CA, school district into community schools. Each has a Family Resource Center, and one third of the families participate in the program. Parents not only receive services, they are offered a range of educational opportunities, become involved, and are empowered to teach other parents, creating a strong community. Many of the parents are immigrants with language barriers. But at the Family Resource Centers, they find a community of other immigrant parents who speak their language playing a leadership role in the schools.

Redwood City community schools work with their partners to engage communities and families to promote school readiness among children. By creating community mobilization teams made up of family members, educators, and other community members who have participated in professional development programs, they enhance family-to-family education and outreach, preparing the community for success. As a result, the families of 70% of students in Redwood City community schools are actively engaged with school campuses through adult education, leadership opportunities, and school meetings. Students whose families participate consistently have shown positive gains in attendance and in English language proficiency for English learners.

Source: United Way Bay Area. (n.d.). Community schools: Redwood City 2020. San Francisco, CA: United Way Bay Area.

Finding 8. The collaborative leadership, practice, and relationships found in community schools can create the conditions necessary to improve student learning and well-being, as well as improve relationships within and beyond the school walls. The development of social capital and teacher-peer learning appear to be the factors that explain the link between collaboration and better student achievement.

Finding 9. Comprehensive community school interventions have a positive impact, with programs in many different locations showing improvements in student outcomes, including attendance, academic achievement, high school graduation rates, and reduced racial and economic achievement gaps.

Finding 10. Effective implementation and sufficient exposure to services increase the success of a community schools approach, with research showing that longer-operating and better-implemented programs yield more positive results for students and schools.

Finding 11. Existing cost-benefit research suggests an excellent return on investment of up to $15 in social value and economic benefits for every dollar spent on school-based wraparound services.

Finding 12. The evidence base on comprehensive community schools can be strengthened by well-designed evaluations that pay close attention to the nature of the services and their implementation.

Research-Based Lessons for Policy Development and Implementation

Community school strategies hold considerable promise for creating good schools for all students, but especially for those living in poverty. This is of particular relevance in the face of growing achievement and opportunity gaps at a moment in which the nation faces a decentralization of decision making about the use of federal dollars. State and local policymakers can specify community schools as part of ESSA Title I set-aside school improvement plans and in proposals for grants under Title IV. And if a state or district lacks the resources to implement community schools at scale, it can productively begin in neighborhoods where community schools are most needed and, therefore, students are most likely to benefit.

Based on our analysis of this evidence, we identify 10 research-based lessons for guiding policy development and implementation.

Lesson 1. Integrated student supports, expanded learning time and opportunities, family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership practices appear to reinforce each other. A comprehensive approach that brings all of these factors together requires changes to existing structures, practices, and partnerships at school sites.

Lesson 2. In cases where a strong program model exists, implementation fidelity matters. Evidence suggests that results are much stronger when programs with clearly defined elements and structures are implemented consistently across different sites.

Lesson 3. For expanded learning time and opportunities, student access to services and the way time is used make a difference. Students who participate for longer hours or a more extended period receive the most benefit, as do those attending programs that offer activities that are engaging, are well aligned with the instructional day (i.e., not just homework help, but content to enrich classroom learning), and that address whole-child interests and needs (i.e., not just academics).

What Do Expanded Learning Time and Opportunities Look Like in Action?

In the ExpandED Schools national demonstration, 11 elementary and middle schools in New York, NY, Baltimore, MD, and New Orleans, LA, partner with experienced community organizations to expand the learning day. They create or expand time for subjects such as science, and they offer arts, movement, small group support, and project-based learning activities that require creative and critical thinking. The result: Students get about 35% more learning time than their peers in traditional public schools. Together with their community partners, ExpandED School leaders re-engineer schools to align their time and resources to meet shared goals for students. Community organizations add to faculty by bringing in teaching artists and AmeriCorps members, among others. Teachers have the flexibility to work beside community educators as students explore enrichment and leadership opportunities that would otherwise be squeezed out of the school day.

Source: ExpandED Schools. (n.d.). Three ways to expand learning. New York, NY: ExpandED Schools.

Lesson 4. Students can benefit when schools offer a spectrum of engagement opportunities for families, ranging from providing information on how to support student learning at home and volunteer at school, to welcoming parents involved with community organizations that seek to influence local education policy. Doing so can help in establishing trusting relationships that build upon community-based competencies and support culturally relevant learning opportunities.

Lesson 5. Collaboration and shared decision making matter in the community schools approach. That is, community schools are stronger when they develop a variety of structures and practices (e.g., leadership and planning committees, professional learning communities) that bring educators, partner organizations, parents, and students together as decision makers in development, governance, and improvement of school programs.

Lesson 6. Strong implementation requires attention to all elements of the community schools model and to their placement at the center of the school. Community schools benefit from maintaining a strong academic improvement focus, and students benefit from schools that offer more intense or sustained services. Implementation is most effective when data are used in an ongoing process of continuous program evaluation and improvement, and sufficient time is allowed for the strategy to fully mature.

Lesson 7. Educators and policymakers embarking on a community schools approach can benefit from a framework that focuses on creating school conditions and practices characteristic of high-performing schools and ameliorating out-of-school barriers to teaching and learning. Doing so will position them to improve outcomes in neighborhoods facing poverty and isolation.

Lesson 8. Successful community schools do not all look alike. Therefore, effective plans for comprehensive place-based initiatives leverage local assets to meet local needs, while understanding that programming may need to be modified over time in response to changes in the school and community.

Lesson 9. Strong community school evaluation studies provide information about progress toward hoped-for outcomes, the quality of implementation, and students’ exposure to services and opportunities. The impact that community schools have on neighborhoods is also an area that could be evaluated. In addition, quantitative evaluations would benefit from including carefully designed comparison groups and statistical controls, and evaluation reports would benefit from including detailed descriptions of their methodology and the designs of the programs.

Lesson 10. The field would benefit from additional academic research that uses rigorous quantitative and qualitative methods to study both comprehensive community schools and the four pillars. Research could focus on the impact of community schools on student, school, and community outcomes, as well as seek to guide implementation and refinement, particularly in low-income, racially isolated communities.

What Does a Comprehensive Community School Look Like in Action?

The class assignment: Design an iPad video game. For the player to win, a cow must cross a two-lane highway, dodging constant traffic. If she makes it, the sound of clapping is heard; if she’s hit by a car, the game says, “Aw.”

This assignment is not for gifted students at an elite school, but for 2nd graders in the Union Public Schools district in the eastern part of Tulsa, OK. Here more than one third of the students are Latino, many of them English learners, and 70% receive free or reduced-price lunch. From kindergarten through high school, they get a state-of-the-art education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Beginning in 2004, Union started revamping its schools into what are generally known as community schools. These schools open early, so parents can drop off their kids on their way to work, and stay open late and during summers. They offer students the cornucopia of activities—art, music, science, sports, tutoring—that middle-class families routinely provide. They operate as neighborhood hubs, providing families with access to a health care clinic in the school or nearby; connecting parents to job-training opportunities; delivering clothing, food, furniture and bikes; and enabling teenage mothers to graduate by offering day care for their infants.

This environment reaps big dividends—attendance and test scores have soared in the community schools, while suspensions have plummeted.

Source: Kirp, D. (2017, April 1). Who needs charters when you have public schools like these? The New York Times.

While we may call for additional research and stronger evaluation, evidence in the current empirical literature clearly shows what is working now. The research on the four pillars of community schools and the evaluations of comprehensive interventions, for example, shine a light on how these strategies can improve educational practices and conditions and support student academic success and social, emotional, and physical health.

As states, districts, and schools consider the best available evidence for designing improvement strategies that support their policies and priorities, the effectiveness of community school approaches offers a promising foundation for progress.

This report is published jointly by the Learning Policy Institute and the National Education Policy Center.

Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence (research brief) by Anna Maier, Julia Daniel, Jeannie Oakes, and Livia Lam is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was made possible, in part, by funding to NEPC from the Ford Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation. This work does not necessarily represent the views of these funders.