Summary

Providing engaging and comprehensive learning experiences—deeper learning—to all students will require new school structures and classroom practices. This transformation will depend heavily on school leaders, given their strong influence on teacher working conditions, classroom instruction, school environments, and student learning. This brief explores five leadership preparation and in-service programs that help school leaders acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to enable, encourage, and sustain deeper learning. It describes the dimensions of deeper learning leadership and articulates the program practices aligned to those dimensions: follow a deeper learning vision, align priorities with equity, create and emphasize learning communities, model the instruction leaders should promote, and teach systemic thinking. The brief concludes with policy recommendations that can support wider adoption of the features and practices highlighted.

The book on which this brief is based, Preparing Leaders for Deeper Learning, is available here.

Introduction

The evolving and interconnected world of the 21st century has been marked by rising expectations for education systems. To meet these expectations, schools must help all learners develop enhanced capacities for critical reasoning, knowledge application, and problem-solving along with the analytical and communication skills needed for lifelong learning in a dynamic environment.Brown, A. (2016, October 6). Key findings about the American workforce and the changing job market. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2016/10/06/key-findings-about-the-american-workforce-and-the-changing-job-market/; National Research Council. (2012). Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13398; Donohue, T. J. (2017, August 28). Building a 21st century workforce. U.S. Chamber of Commerce. https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/education/building-21st-century-workforce; Moeller, J. O. (2017, November 16). Struggle to prepare the workforce for a fast-changing world. YaleGlobal Online. https://archive-yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/struggle-prepare-workforce-fast-changing-world-0. Meeting these expectations requires a transformation of school structures and classroom practices, reorienting them toward providing engaging and comprehensive learning experiences—deeper learning—to all students.

This systemic transformation will depend heavily on school leaders, who strongly influence teacher working conditions, classroom instruction, school environments, and student learning.Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. Wallace Foundation. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/how-principals-affect-students-and-schools-a-systematic-synthesis-of-two-decades-of-research.aspx; Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600565829; Leithwood, K., & Riehl, C. (2005). What we know about successful school leadership. In W. Firestone & C. Riehl (Eds.), A new agenda: Directions for research on educational leadership (pp. 22–47). Teachers College Press; Louis, K. S., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K. L., & Anderson, S. E. (2010). Investigating the links to improved student learning: Final report of research findings. Wallace Foundation. https://wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning.pdf Therefore, school leadership preparation and development will need to evolve to focus on the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to enable, encourage, and sustain deeper learning. Preparing Leaders for Deeper Learning, the book on which this brief is based, highlights five programs that exemplify distinct approaches to school leadership preparation and professional development, describing what deeper learning leadership looks like in practice and how these programs successfully prepare principals for it.

The following five programs are featured in this study:Data for this study were collected between the spring of 2017 and the spring of 2018.

- The University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) Urban Education Leadership program is an intensive, clinically based multiyear and multiphase program. The first phase, which qualifies participants for the Illinois P–12 Principal Endorsement, integrates coursework with a fully funded, full-time residency in Chicago Public Schools in which the participant is supported by a mentor principal and university coach. The second phase, which leads to a doctoral degree, offers participants additional coursework and coaching while they work as school administrators.

- The Principal Leadership Institute (PLI) at the University of California, Berkeley is a master’s program that prepares school leaders to improve educational opportunities for historically underserved students in California’s public schools. Participants complete 4 semesters of coursework and engage in identity-, equity-, and inquiry-based learning activities in structured cohorts. Those who complete the program qualify for a Preliminary Administrative Services Credential.

- The Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD) leadership pipeline develops leaders for all levels of the local system, from assistant principals to cabinet-level staff. Pipeline programs build on one another, starting with the Future Administrators Program, which supports staff in becoming school administrators, and the Aspiring Principals Program, which prepares candidates to move from assistant principal to principal positions. These 1-year programs provide a series of learning opportunities and supports through workshops, site observations, and mentoring.

- The Arkansas Leadership Academy’s Master Principal Program (MPP) is an in-service professional learning program that supports school leaders in creating equitable deeper learning environments and catalyzing system improvement. The 3-phase program develops leadership skills and knowledge through intensive residential sessions bridged by school-based research and activities. Principals who complete all 3 phases are eligible to apply for recognition as a Master Principal in Arkansas, a selective designation that carries statewide recognition and financial incentives.

- The National Institute for School Leadership (NISL) serves school administrators in all stages of development across the country. It is implemented by the National Center on Education and the Economy, a nonprofit organization, in close partnership with states and districts and is delivered through in-person workshops facilitated by specially trained instructors. The program is driven by a research-based curriculum that emphasizes school leaders as drivers of equitable and transformative change that culminates in deeper learning and enhanced achievement for students.

What Is Deeper Learning?

Deeper learning, based on the science of learning and development (SoLD), is a holistic account of how people learn. It describes the comprehensive learning experiences through which students:

- acquire deep content knowledge and apply it to contexts and new problems;

- develop critical reasoning, problem-solving, and inquiry skills;

- build their collaboration and communication skills;

- enhance their abilities to set goals, create plans, actively engage in tasks, and evaluate their own learning; and

- develop social and emotional awareness and mindsets for school, college, and career.

Deeper learning instruction is inquiry based and student centered; builds on students’ assets and experiences; includes scaffolded activities and formative feedback; is based on challenging goals that foster motivation and engagement; and occurs in positive classroom environments that support the whole child.

Sources: Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. National Research Council; Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140; Darling-Hammond, L., & Oakes, J. (2019). Preparing teachers for deeper learning. Harvard Education Press.

Dimensions of Deeper Learning Practice and Development

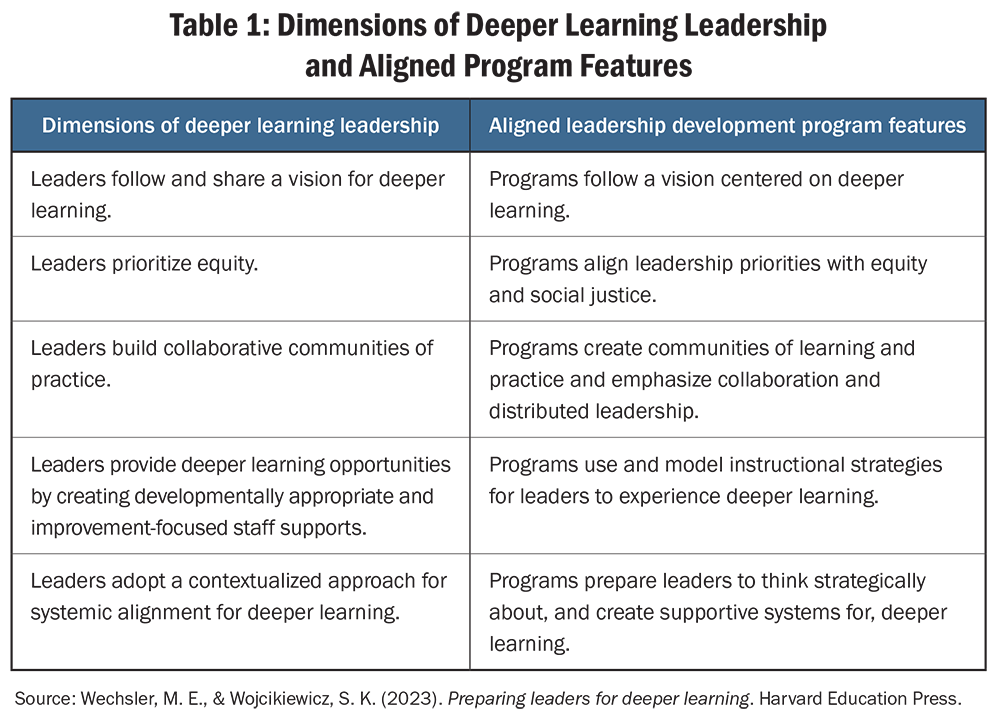

Creating deeper learning educational environments requires a new conception of effective school leadership. Through a comparative analysis of the programs, we identified five dimensions of leadership for deeper learning. Then, for each dimension, we identified aligned program structures and practices that support their development (see Table 1).

A Vision Centered on Deeper Learning

Deeper learning leaders adopt a vision focused on developing students’ deeper learning competencies. They follow that vision in their actions and intentionally build systems, cultures, and norms to enact it in schools. To develop deeper learning leaders, leadership development programs articulate and implement their own visions for teaching, learning, and leadership that embrace the principles of deeper learning.

The LBUSD Leadership Development Pipeline, for example, is grounded in the instructional vision of the district, the Understandings Curriculum, which articulates that student learning should be collaborative, cognitively demanding, and relevant. This vision guides leaders in organizing and facilitating teacher development and measuring instructional effectiveness. By foregrounding this vision in leadership pipeline programs, LBUSD equips administrators with the skills and mindset to have a similar vision that they bring to their schools. NISL likewise focuses on a conception of student learning that emphasizes college and career readiness for all students; social and emotional learning and academic development; and deep understanding, synthesis, and collaboration. This vision informs all program structures and practices.

Priorities Aligned With Equity

Deeper learning leaders prioritize equity and social justice. They know the social, historical, economic, and political contexts of their communities and understand how these factors shape student learning. They believe that all students are capable of learning and achieving at high levels, and they structure opportunities to enact that belief while seeking out, and working to resolve, opportunity gaps. To develop deeper learning leaders, leadership development programs emphasize equity and provide experiences that prepare leaders to make deeper learning a priority. They also recruit candidates from diverse backgrounds who have the dispositions to engage with and confront inequities. Programs then provide these leaders with opportunities to address inequities through coursework and field experiences.

UIC, for example, recruits participants who demonstrate a commitment to social justice and constructs cohorts that reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the Chicago Public Schools student population. The program infuses equity throughout all courses and places residents in schools that prioritize equity, immersing them in the challenges and strategies of addressing educational inequities.

A core value of UC Berkeley’s PLI is disrupting inequity and striving for social justice. The PLI demonstrates these values by building racially, ethnically, socioeconomically, and professionally diverse cohorts and prioritizing applicants with clear commitments to equity. It also brings a social justice lens to each course with assignments like its community-mapping project, in which candidates learn how to identify and leverage community assets to “make high-quality learning accessible to all students.”University of California, Berkeley School of Education. Principal Leadership Institute. https://bse.berkeley.edu/pli

Collaborative Communities of Learning and Practice

Deeper learning leaders enact leadership as a collaborative endeavor with teachers and create the time and structures to enable collaboration. They distribute leadership responsibilities and decision-making, making good use of others’ expertise, and empower others with opportunities to be change agents. To develop deeper learning leaders, leadership development programs create collaborative communities of practice, often operationalized through a cohort structure. These learning communities serve as a tool for instruction and reflection. Programs place participants into cohorts to enable shared inquiry, create safe environments to discuss ideas and ask questions, and provide opportunities for participants to grapple as a group with what it means to lead for deeper learning. Participants can build on their peers’ knowledge and offer academic, social, and emotional support to one another.

Participants in the Arkansas MPP attend residential sessions and work together to complete activities between sessions. This collaborative component enables leaders to practice key elements of leading for deeper learning as they share ideas, collaborate, and practice giving and receiving useful feedback. Berkeley’s PLI also uses a cohort model, then further divides cohorts into work groups of four or five candidates, who are intentionally selected based on their diverse backgrounds and skills, to complete structured assignments that scaffold their growth. One program faculty member noted that as participants’ learning progresses, the “cohorts are true learning communities. … They know each other well, they’ve built a trust in the room, they’re willing to share in ways they would not share at Unit 1.”

As participants experience collaborative learning, they develop the capacity to create and use similar collaborative structures in their own schools. Being part of a community of practice helps participants see the advantages of distributed leadership as they acquire the knowledge and skills to implement it. The LBUSD leadership pipeline models collaboration through administrator-run workshops, mentoring from practicing administrators, collaborative inquiry and evaluation visits, and participation in school instructional leadership activities. As a district administrator explained, “We really prioritize collaboration, planning, and getting better together and being learners together.”

Developing the capacity for distributed leadership is also a focus throughout the Arkansas MPP. In one assignment, for example, leaders complete a self-assessment of their effectiveness at delegation and work in small groups to identify shifts they can make to share tasks more effectively. Through this and other assignments, principals learn to create school environments where shifts toward deeper learning are driven by many staff members, not just the principal.

The Use and Modeling of Deeper Learning Instructional Strategies

Deeper learning leaders provide staff members with developmentally grounded and personalized learning opportunities that reflect the opportunities they expect teachers to offer in their own classrooms. They understand staff members’ abilities and focus professional development on the skills and knowledge needed to create deeper learning classrooms. Deeper learning leaders also create teacher accountability systems focused on continuous improvement and empowerment.

To develop deeper learning leaders, leadership development programs utilize coursework and clinical experiences to show leaders, through example and participation, what deeper learning is and how to bring it to life in their schools. By modeling deeper learning instructional strategies in courses, the programs enable participants to experience this type of learning. As program participants shadow mentor principals, immerse themselves in residencies, and work through realistic scenarios and case studies of exemplary leadership practices, they both observe and participate in leadership for deeper learning. These models and experiences help them better understand what deeper learning leadership looks like in practice.

NISL, for example, models problem-based teaching methods to prepare participants to recognize and enact deeper learning tenets in their schools. Participants practice strategic decision-making and other leadership competencies through case studies, simulations, and role-plays. One NISL state coordinator explained, “If I, the leader, don’t know what [deeper learning] looks like for me, then there’s no way that I’m going to be able to re-create the environment and conditions in which that can happen for my kids in my building.”

Programs also emphasize developmentally grounded and personalized instruction in their own coursework, coaching, and assessment, modeling how principals can support their teachers. At UIC, residents develop and continually revise personalized professional development plans with their coaches, who also conduct weekly site visits and provide feedback on issues of practice. Further, residents’ progress is assessed in monthly “triad” meetings of the resident, mentor principal, and coach. The Arkansas MPP requires principals to self-diagnose their strengths and areas for development based on the program’s leadership performance rubrics. Principals document what they have learned, how they have applied their learning, their failures and successes, and their plans for next steps.

Another deeper learning instructional strategy embraced by the programs is authentic, job-embedded learning. Leaders focus on real problems of practice in learning experiences that are engaging and applicable to the challenges they will face as administrators. In the Berkeley PLI, assignments push candidates to apply theory to their work, collect data at their schools, and conduct analyses through action research. In LBUSD’s pipeline programs, workshops run by practicing administrators include presentations, work-throughs of real administrative issues, and discussions applied to practice. By shadowing practicing administrators and working with mentors, candidates see and participate in school and instructional leadership while applying their learning in real-world applications.

The Creation of Supportive Systems for Deeper Learning

Deeper learning leaders take a systems perspective to school change grounded in their local context. They know the potential levers for lasting change and how to use them strategically, based on the understanding that deeper learning carries over from leaders to teachers to students. They are also diagnosticians, able to use a wide array of data to understand strengths and areas for development as they strive for continuous improvement in classrooms, schools, and the district.

To develop deeper learning leaders, leadership development programs include a focus on systems change and strategic thinking. Leaders learn to create supportive environments for change, to lead and participate in inquiry around system performance and improvement, and to work collaboratively to implement decisions. This emphasis on strategic and systemic thinking and action gives leaders the tools to support the deeper learning practices they are being prepared to implement.

NISL’s theory of action focuses on systems change at scale, and the program positions principals as strategic thinkers who approach decisions in a strategic way. Program assignments reflect this view, as exemplified by the action research projects in which participants develop a vision for student learning in their school communities and create an action plan to achieve that goal. Likewise, instructors in the Berkeley PLI highlight specific systemic change strategies that leaders can employ to increase equitable outcomes for all students. In assessment sessions, candidates engage in simulated scenarios in which they provide instructional leadership, interpret data for school improvement, and analyze levers for systemic change. Additionally, the program’s action research project requires participants to identify an equity issue in their school and lead cycles of inquiry to analyze, develop, implement, and adapt systemic approaches to school improvement. One PLI faculty member explained that leaders should be able to “take a step back and see the big picture … of how they’re going to help to build up their school site and their community.”

Factors That Support Deeper Learning Leadership Development

To successfully implement the dimensions of leadership preparation for deeper learning, programs give significant attention to their own structures and systems.

A Culture of Continuous Improvement

Just as programs teach leaders to embrace continuous improvement, program staff engage in continuous learning for program improvement. They conduct cycles of data collection, analysis, reflection, and program revisions to enhance their own capacity to build candidates’ deeper learning leadership capabilities. At UIC, for example, five full-time doctoral-level research staff study program impact using a comprehensive participant data-tracking system. Based on the findings, UIC has revamped courses, improved tools and protocols, enhanced collaboration with Chicago Public Schools, bolstered funding streams, and connected program completion to the improvement of organizational capacity and performance. NISL, too, conducts constant refinement. It has refined its conceptual framework for leadership development, created stronger connections across curriculum units, and shifted to a more analytic approach in its teaching case studies. NISL has hired staff to carry out a formative evaluation to support facilitators and improve the curriculum while engaging with external evaluators to understand the program’s impact and inform program improvement.

Internal Capacity-Building

Programs also take steps to build internal capacity. The Berkeley PLI builds program capacity through the intentional recruitment, training, and support of coaches. The PLI combines a rigorous, multistage hiring process for coaches with intensive training and monthly collaborative seminars. NISL also invests in preparing and supporting program facilitators. Potential facilitators must apply to NISL’s facilitator certification institute, complete the 6-day program, and prepare a video-based performance assessment. After certification, NISL facilitators regularly complete formative assessments, and all facilitators receive ongoing support from national staff and at conferences.

Systemic Change Efforts at the District and State Levels

Programs also support change at the district and state levels. UIC’s yearlong residency is made possible by its partnership with Chicago Public Schools. Additionally, the district has provided financial support for the program since its inception, and UIC, in turn, has hired a formal liaison to the district. Likewise, Berkeley’s PLI leverages its partnerships with four nearby districts to strengthen recruitment and assemble racially and ethnically diverse and talented cohorts. The Arkansas Leadership Academy takes a different tack, working beyond the MPP to spark systemwide educational improvements. The MPP is one in a suite of offerings by the Arkansas Leadership Academy, including programs for assistant principals, teacher leaders, school leadership teams, and district administrators. These programs are part of the combined effort to support the transformation of teaching and learning and provide opportunities for school and district personnel to collaboratively build a foundation for deeper learning.

Policies for Leadership Development

The features of the leadership development programs described in this brief provide ideas and guidance for program development and improvement. Yet leadership preparation and development programs do not operate in a vacuum; program-level efforts succeed or fail in the context of education systems shaped by local, state, and federal policies. Therefore, we offer the following five recommendations for program administrators and state policymakers:

- Define and operationalize high-quality leadership practice. A key feature of the leadership development programs is their articulation and enactment of a vision aligned with deeper learning. Through standards, requirements, and expectations for school leaders, states can incentivize and support leadership preparation programs’ adoption and enactment of visions aligned with deeper learning.

- Incorporate performance assessments to evaluate principals’ effectiveness. Performance assessments can authentically measure candidates’ capacity to lead for deeper learning, inform the personalization of support for candidates, and create connections between program learning opportunities and the work of school leadership. State and program adoption of performance assessments can influence program design and ensure that program completers have the requisite knowledge and skills to lead for deeper learning.

- Provide funding and supports for high-quality clinical partnerships. Support for clinical partnerships can ensure that internships and residencies—critical features of high-quality preparation—become universal and sustainable. Partnerships between leadership preparation programs and K–12 districts that include joint financial support, design input, and responsibility can ensure a clear and consistent vision for deeper learning. States can support successful partnerships by serving as collaborators and funders and by requiring formal partnerships between preparation programs and school districts.

- Create pipelines for promising candidates. Leadership pipelines with a deeper learning focus should start with recruiting deeper learning–oriented teachers and support their preparation, induction, and professional learning opportunities. Administrators further along the pipeline can serve as mentors for those in the earlier stages, creating consistency in vision and priorities for deeper learning.

- Encourage targeted recruitment of leadership candidates. Targeted recruitment allows schools, districts, and programs to identify candidates with deeper learning leadership potential who are part of historically underserved populations, rather than choosing leaders from self-selected candidates who can afford the time and expense of leadership training.

- Underwrite leader training. Funding for tuition expenses, along with paid internships and residencies, can enable high-quality candidates to complete preparation programs and enter school leadership without going into debt. This funding also makes it feasible for candidates to take the necessary time to pursue robust clinical placements that characterize deeper learning–aligned programs. Removing or mitigating financial constraints can make leadership preparation more accessible to a broader range of applicants.

Conclusion

Principals who lead for deeper learning build systems and support teachers so that students develop the knowledge and skills they need to be successful in today’s world. This brief offers examples and guidance for policymakers, principal preparation and professional development program staff, and district administrators for creating and sustaining programs that focus on the knowledge and skills principals need to lead for deeper learning. Leadership development for deeper learning takes many forms, though its core elements can be described succinctly: Follow a deeper learning vision, align priorities with equity, create and emphasize learning communities, model the instruction leaders should promote, and teach systemic thinking. These dimensions encompass the elements of high-quality professional learning while embodying deeper learning principles.

While it is expected that school leaders have a vision, deeper learning leaders center that vision on active-learning pedagogies, equity, and education of the whole child. All school leaders develop their staff, but deeper learning leaders do so in a way that reflects deeper learning for adults and builds staff capacity to enact the same practices in classrooms. The visions, structures, and practices described in this brief enable programs to develop not only high-quality principals, but high-quality principals who are able to promote deeper learning and equity.

Related Resources

Developing Deeper Learning Leaders (brief) by Marjorie E. Wechsler and Steven K. Wojcikiewicz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Additional core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.