Strengthening Pathways Into the Teaching Profession in Texas: Challenges and Opportunities

Summary

Systemic challenges for the Texas teacher workforce result from a large yearly demand for new teachers, exacerbated by high and climbing teacher attrition rates. As a result of these challenges, a large majority of new teachers are now hired before they complete preparation. Assigned disproportionately to students from low-income families and students of color, these less-prepared teachers are demonstrably less effective and less likely to stay than fully prepared teachers, stimulating further shortages. This study examines these conditions; describes the substantial work underway in Texas to address teacher shortages and stabilize the teacher workforce; and synthesizes evidence about policy interventions that can help address the key factors influencing workforce stability. These include investing in high-quality preparation models; reducing financial barriers to entry for teacher candidates; increasing teacher compensation; supporting improvements to teacher induction and working conditions; and improving state educator workforce data.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

This brief summarizes teacher workforce challenges and recent initiatives in Texas that are shaping the state of the educator workforce in important ways. Ongoing teacher shortages have led to the creation of a wide range of pathways into the profession, featuring varying types and amounts of training. The majority of first-time teachers in Texas are now entering the profession either through alternative certification routes that often include little to no student teaching or without any certification at all, resulting in a workforce that has experienced increasingly little preservice clinical practice before taking on responsibilities for teaching children.

A growing body of research demonstrates that these differences in pathways are associated with meaningful differences in teachers’ knowledge, skills, and effectiveness, as well as the rates at which they enter and leave the profession. Research has found that teachers who are not fully prepared when they enter the profession—now a majority of newly hired Texas teachers—are, on average, both less effective and more likely to leave, creating high rates of churn, which also undermines student achievement at the school level. These differences have implications for student learning, school management, and equity, since the districts that have the most difficulty hiring fully prepared teachers are those serving the most students of color and students from low-income families.

This brief summarizes an accompanying Learning Policy Institute (LPI) report that synthesizes the emerging research; describes the substantial efforts Texas leaders and institutions are making to address concerns about workforce preparation and stability; and provides additional actionable, research-based policy recommendations.

Background

Major initiatives are underway in Texas to strengthen routes into the teaching profession, including a newly launched, innovative statewide teacher residency program. Such initiatives are responding to recent research that identifies an increasingly unstable statewide teacher workforce, weakened by high annual attrition rates and a teacher pipeline bifurcated by preprofessional experiences that differ substantially in structure and content.

Texas has the largest teacher workforce of any U.S. state, numbering over 370,000 teachers in 2021–22.Texas Education Agency. (2022). Employed teacher attrition and new hires 2007–08 through 2021–22. (accessed 12/06/22); State Nonfiscal Public Elementary/Secondary Education Survey Data, 2021, from the Common Core of Data, National Center of Education Statistics. A high yearly demand for new teachers, exacerbated by higher teacher attrition rates than the national average, creates unique systemic challenges. Workforce shortages, already present before the onset of COVID-19 but accelerated by pandemic-era teaching conditions, only increase this demand, pushing the number of new hires to more than 40,000 per year.Texas Education Agency. (2022). Employed teacher attrition and new hires 2007–08 through 2021–22. (accessed 12/06/22). The robustness of the preparation pipeline—in terms of quantity and quality—is thus a continuous and growing concern for Texas policymakers.

In March 2022, by directive of Governor Greg Abbott, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) created a statewide Teacher Vacancy Task Force to further study statewide teacher workforce shortages and make recommendations for state policy changes that continue to address them. To inform legislative staff and members of the task force, this brief summarizes and builds on the research on teacher supply, demand, and attrition, and the outcomes of different pathways into the Texas teacher workforce. We then discuss the work already being done in Texas to address workforce instability and provide additional actionable, research-based policy recommendations to further the state’s efforts.

Teacher Workforce Trends in Texas

Texas has experienced teacher shortages and workforce instability driven by high attrition rates for decades. Shortages have been especially acute in mathematics, special education, career technical education, and bilingual/English as a Second Language instruction, and have been more prevalent in rural communities and in large urban districts. Gaps between supply and demand are expected to grow more pronounced due to COVID-19–era increases in teacher resignations. In a recent statewide poll, 77% of Texas teachers indicated that they had thought seriously about leaving the profession; over 90% of those teachers had taken at least one step to do so.Charles Butt Foundation. (2022). The 2022 Texas teacher poll: Persistent problems and a path forward. (p. 10).

This workforce instability has resulted from several intersecting trends:

A growing need for additional teachers. The number of Texas teaching positions has grown steadily for over a decade, as a function of both population increases and decreases in class size. More recently, the influx of federal COVID-19 recovery dollars has also created more positions to be filled. The Texas teacher workforce is now at its largest size ever—over 370,000 teachers in 2021–22.Texas Education Agency. (2022). Employed teacher attrition and new hires 2007–08 through 2021–22. (accessed 12/06/22); State Nonfiscal Public Elementary/Secondary Education Survey Data, 2021, from the Common Core of Data, National Center of Education Statistics.

High levels of teacher attrition, compounded by the effects of the pandemic. Texas has outpaced national teacher attrition averages by approximately 25% over the past decade.State attrition rate data: Texas Education Agency. (2022). Employed teacher attrition and new hires 2007–08 through 2021–22. (accessed 12/06/22); National attrition rate data: National Association of Secondary School Principals (2020). How school leadership affects teacher retention. In 2021 alone, more than 1 in 9 Texas teachers left the state’s teacher workforce rather than return for the 2021–22 school year.Marder, M., Reyes, P., Marshall, J., Alexander, C., Martinez, C.R., & Maloch, B. (2022). Texas educator preparation pathways study: Developing and sustaining the Texas educator workforce. University of Texas at Austin College of Education. Recent changes in the difference between new teacher hires and teacher attrition also illuminate the extent to which workforce instability drives teacher shortages in Texas: in 2021–22, nearly the entire statewide demand for teachers was to offset attrition. The expectation for 2022–23 is that an even higher proportion of teachers will need to be replaced, further challenging the capacity of the teacher development system to keep up.

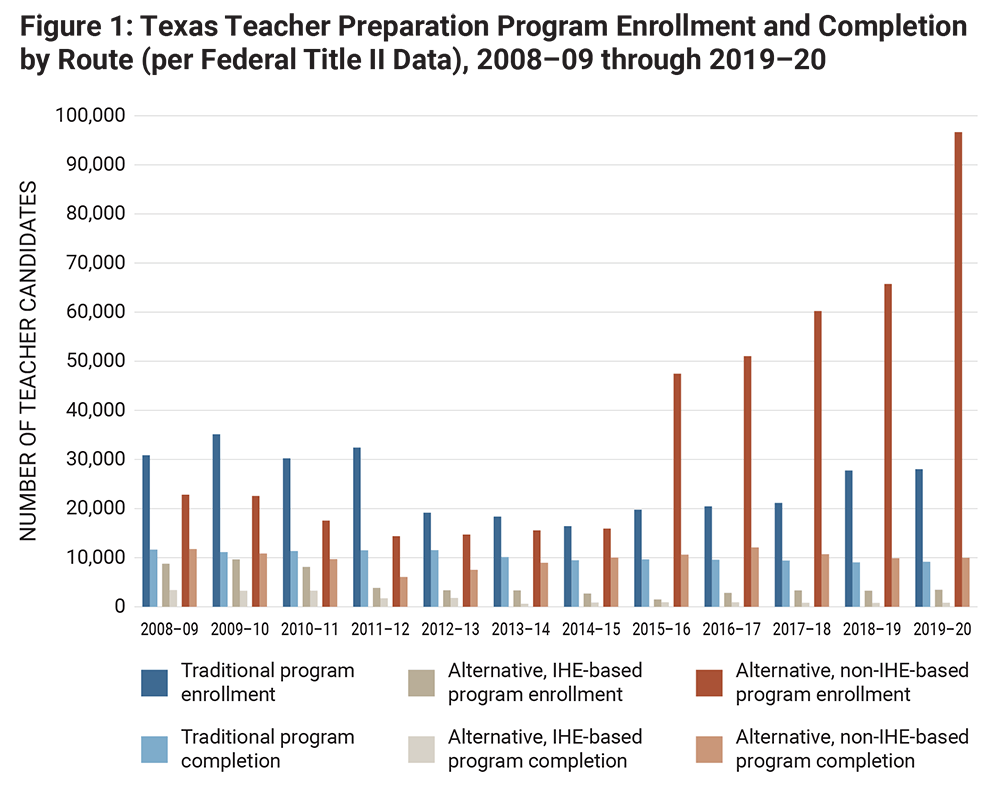

Increasing reliance on alternative certification programs that have low program completion rates and high attrition rates from the teaching profession. A majority of new teachers in Texas are now certified through alternative routes with substantially lower program completion rates and lower retention rates in the profession than traditional preservice programs. Concerns are particularly acute with for-profit alternative pathways, which have increased their enrollment by more than 500% over the past 5 years without increasing the number of program completers. Whereas around a third of traditional-route enrollees graduate each year from their multiyear (mostly undergraduate) programs, only about one tenth of those in non-university alternative route programs graduated in 2020. (See Figure 1.)

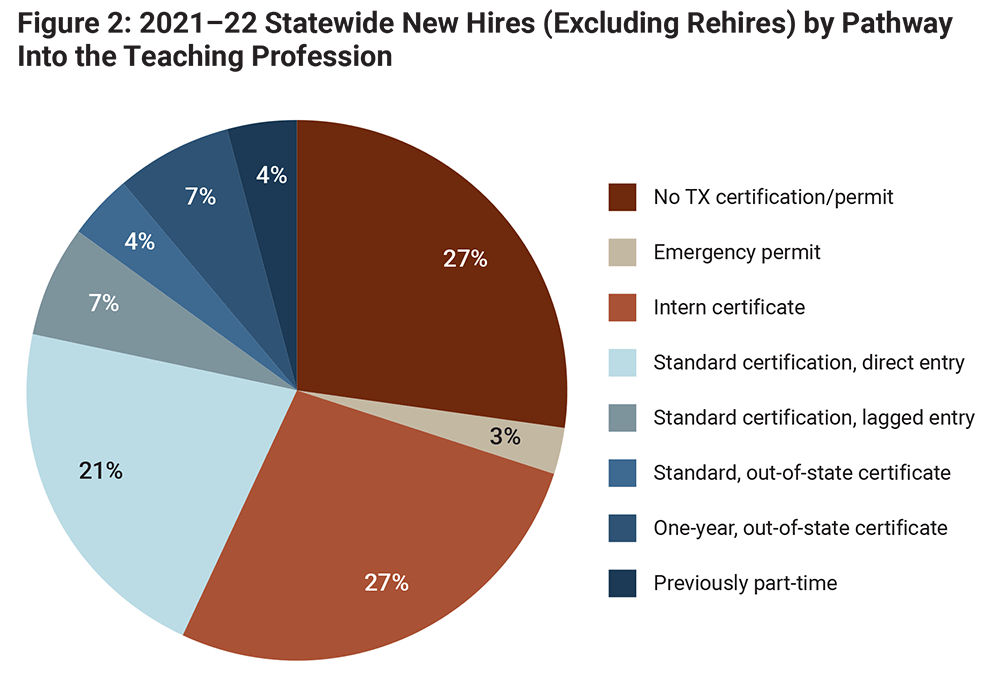

A shrinking pool of fully credentialed new teachers. Teachers who earned a standard certificate after completing a full complement of coursework and student teaching in Texas made up only 28% of statewide first-time teacher hires in 2021–22 (see Figure 2). Studies show that these fully prepared graduates are considerably more likely to stay in teaching than those who enter without full preparation. Five years after their first year of full licensure in 2016–17, 69% of teachers from traditional preservice programs remained in Texas classrooms, versus 60% of teachers who completed alternative preparation programs.Texas Education Agency. (2022). Teacher retention by preparation route 2015–16 through 2020–21. (accessed 12/06/22). In addition, as noted above, many of those who enroll in alternative programs do not appear to complete those programs and become certified.

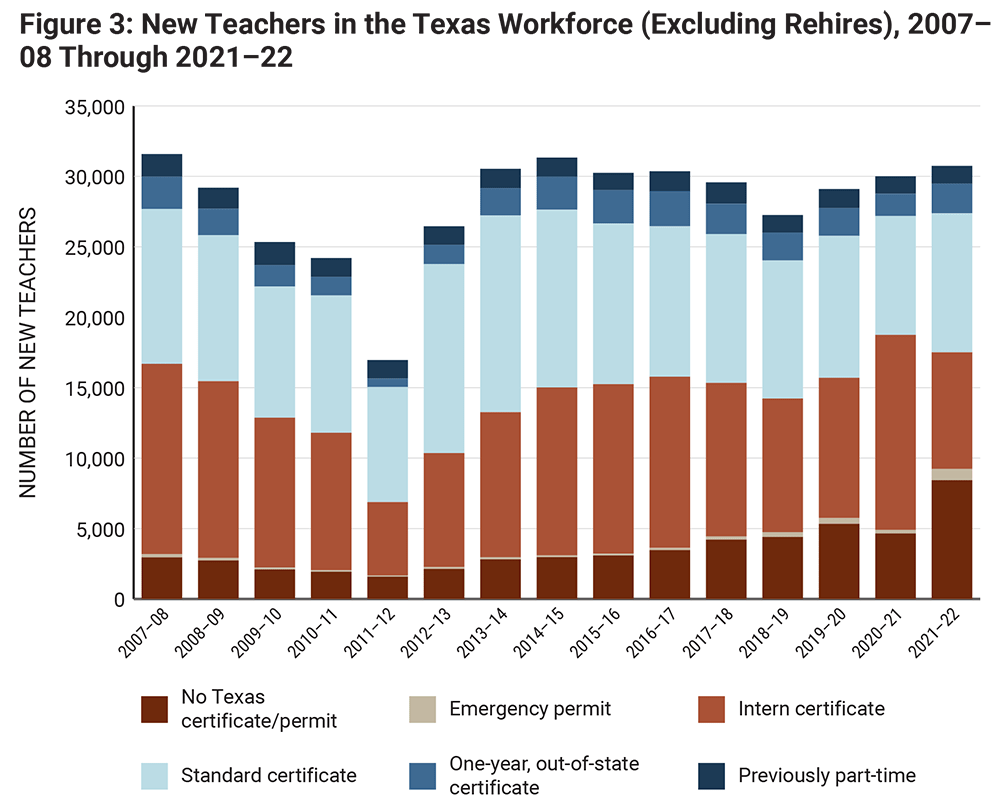

Increasing reliance on interns and, more recently, on uncertified teachers. In 2021–22, 57% of first-time teachers in Texas held either a substandard intern certificate or emergency permit (30%) or no certification at all (27%) (see Figure 2). With approximately 74% of districts now able to hire uncertified teachers under the state Districts of Innovation designation,As of 2022, 85% of Texas districts self-identified as Districts of Innovation, with 87% of that subtotal—74% of total districts—indicating that they have exempted themselves from the requirement to hire certified teachers. The final 74% figure is based on calculations by the authors of this report based on the figures from the sources below: Texas Education Agency. (n.d.). Districts of innovation. (accessed 12/06/22); My Texas Public School. (n.d.). The school system. (accessed 12/06/22); Anglin, K. L. (2021). The role of state education regulation: Evidence from the Texas Districts of Innovation statute [EdWorkingPaper 21-479]. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. and with charter schools also able to hire uncertified teachers, the share of uncertified teachers in the entering workforce has increased substantially over the past few years, having doubled in the past year alone (see Figure 3). Uncertified teachers appear largely to be displacing interns in the state teacher workforce.

The Need to Expand Productive Program Models

Texas’s ongoing teacher shortages are partly a function of the expansion of preparation models that exacerbate a leaky pipeline by failing to graduate a large share of their candidates and failing to prepare them well enough to enable them to stay in the classroom. Texas now has the largest alternative teacher preparation sector in the country and produces more than half of alternatively-prepared teachers in the United States each year.Hoover, C. (2022, June 14). ACP enrollment increases but program completion decreases. Texas Association of School Boards. (accessed 12/06/22). As with traditional teacher preparation programs, alternative pathways vary widely in duration, structure, and rigor, but alternative pathways generally allow an individual to become a teacher of record before completing coursework and with little or no student teaching. As little as 30 hours of field experience is required, and half of these hours can be completed virtually. In contrast, the minimum requirement for field experience for a teacher candidate participating in student teaching prior to serving as a teacher of record is at least 70 full days or 140 half days of experience with students in real classrooms.19 Tex. Admin. Code §228.35; Donaldson, E., Richman, T., & Smith, C. (2022, April 20). Texas’ ‘wild west’ teacher prep landscape could make teacher shortage worse. Dallas Morning News. (accessed 12/06/22).

While both traditional preservice programs and alternative programs are of varying quality, the evidence suggests that the less comprehensive the preparation is that candidates receive in the form of student teaching integrated with several essential kinds of coursework, the more likely they are to struggle in the classroom and the less likely they are to stay in teaching. National data show that teachers who enter without key areas of coursework or clinical preparation are 2 to 3 times more likely to leave within the first year of teaching than those who are fully prepared.Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition? Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

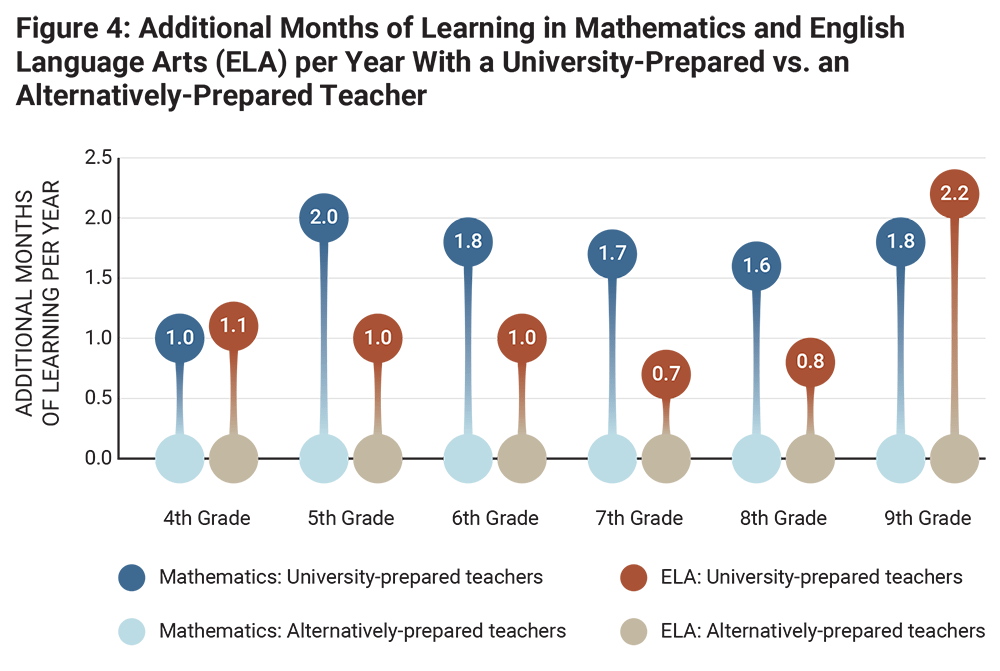

In addition, the lack of comprehensive preparation can affect student learning. A recent report from researchers at the University of Texas at Austin reveals that alumni of alternative certification programs in Texas produce significantly lower student learning gains than alumni of university-based teacher preparation programs. These gaps show up in every tested grade level and subject. For example, students with fully prepared teachers gained 2.2 additional months of learning in 9th grade English language arts (ELA) and 1.8 additional months of learning in 9th grade math compared to those whose teachers entered through alternative routes (see Figure 4).

Similar trends are revealed for students of teachers prepared by nonprofit versus for-profit entities, with students of nonprofit-prepared teachers showing additional weeks to months of learning over students of for-profit–prepared teachers at each grade level in both math and ELA. These gaps in learning accumulate over time when students have a string of underprepared teachers, expanding the achievement gap.

Participation in an alternative rather than a traditional preservice teacher preparation program is also one of the strongest predictors of receiving an out-of-field teaching assignment in Texas (i.e., teaching outside the area in which a teacher is prepared), which is associated with weaker student outcomes. Because alternative certification programs disproportionately place teachers in schools that serve students from low-income families, schools with higher proportions of students of color, and schools that are lower performing, the current conditions create a major equity issue.

Further, while there is growing evidence that Black teachers who are fully certified support improved achievement and attainment for Black students, there is also evidence that Black teachers who are recruited through alternative routes leave teaching at much higher rates than those who receive the benefit of a comprehensive preparation program more often associated with the traditional route into teaching. Research shows that teacher candidates of color tend to have higher debt and less capacity to absorb the costs of preservice preparation programs than White teacher candidates. When financial supports are unavailable, this phenomenon has the effect of siphoning higher proportions of teacher candidates of color into lower-cost alternative programs (where teacher candidates can earn a salary while completing their internships).

Ultimately, the need to maintain a large and effective teaching force necessitates a robust teacher pipeline that prepares candidates well and keeps them in teaching. Some states have reduced or eliminated teacher shortages by raising salaries and investing in candidates’ access to program models that provide them with strong clinical preparation before and after entry that translates into effectiveness and retention.

Texas is already making substantial investments to improve teacher preparation and teaching conditions, supported by federal and state funds and the philanthropic community. A leading example is the High-Quality, Sustainable Residency Program, part of the $1.4 billion Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) suite of initiatives launched in summer 2021. The residency program supports districts, working in collaboration with local teacher preparation programs, in creating partnerships to sustainably fund paid teacher residencies. Nationally, teacher residency programs have been found to produce well-prepared teachers who stay in the profession at very high rates, ending the churn of underprepared teachers that districts otherwise experience.

TCLAS also includes funding for Grow Your Own (GYO) programs, another research-validated, high-retention approach to addressing teacher vacancies. Another recent effort was H.B. 3 of 2019, which raised the minimum pay threshold for Texas teachers and provided substantial additional funding for expert teachers to teach in districts with persistent shortages. (While this increase to teacher base pay was much needed, after accounting for inflation, the increase was only enough to bring teachers back to the level of compensation they were receiving a decade prior.) Key additional support from the philanthropic community includes, for example, technical assistance for teacher residency programs and rich networks of teacher preparation programs working together on continuous improvement.

Policy Recommendations

Given the magnitude of the state’s teacher workforce challenges, sustainably improving teacher preparation and retention in Texas will require building upon the efforts already underway. Policymakers can employ a variety of research-based tools to grow the teacher pipeline, bolster state systems which ensure that all teacher candidates have access to the learning experiences needed to serve all students effectively, and retain more of the teachers already in the classroom. For example, the state can:

- Continue to increase the attractiveness of the teaching profession by equalizing funding and salaries across districts and calling attention to local working conditions. Building on H.B. 3 of 2019, Texas policymakers can examine the competitiveness of wages across districts and consider means to equalize the purchasing power of teacher salaries in different locations across the state. They can also fund working conditions surveys, like those used in many other states, to provide actionable data to local policymakers on how to improve the attractiveness of teaching jobs.

- Subsidize access to high-quality preparation programs by funding service scholarships and/or loan forgiveness for teacher candidates repaid through service in the profession. These programs can open access to the teaching profession, support candidates in choosing high-quality preparation routes, and increase both the size and diversity of the teacher candidate pool. They can also be designed to incentivize teachers to choose high-need subjects and locations.

- Attend to the preparation and professional learning of building administrators to help them support and retain teachers. Because school leaders play a central role in shaping the norms, systems, and culture of schools, policymakers should consider school leadership as a lever for improving professional practice and working conditions. Efforts can include subsidizing principal preparation and supporting the replication of successful programs, as well as the support of purposeful professional development for principals that is focused on helping them create supportive, collegial school environments that enable teachers to become more effective.

- Support expansion and ongoing implementation of high-quality, high-retention pathways such as teacher residency programs. Providing support for demonstrably high-quality, high-retention pathways into the profession—including, but not limited to, residencies like those within the new TCLAS program—could simultaneously increase teacher supply and preparedness while reducing attrition. Such support—including funding as well as technical assistance—can build upon the state’s initial investment. This support should be informed closely by ongoing research into the implementation and effectiveness of the TCLAS residency program and others operating in Texas.

- Develop a range of successful GYO programs that recruit and train teachers from within local communities. These programs can include career pathways that use dual-credit courses and tutoring opportunities to facilitate high school students’ entry into teacher preparation programs, as well as supports to enable paraprofessionals to become prepared as teachers. Incentives to districts and preparation programs, and supports for candidates, can enable more of these high-retention models. State policymakers can also study the success of those GYO programs launched through TCLAS to expand and replicate the most useful models.

- Access federal, state, and local apprenticeship funds to enable teachers to earn and learn as they complete student teaching or residency experiences under the supervision of expert teachers. Texas teacher education programs are beginning to access federal apprenticeship funds to support clinical learning for prospective teachers. The state can facilitate this access by allocating some of its state discretionary funds for this purpose and by documenting and disseminating successful local program models.

- Strengthen all routes to certification through performance-based program approval and accountability strategies that ensure supports for candidates and data for program improvement. Providing common data about candidate experiences and preparedness as well as program outcomes such as completion, entry, and retention rates in teaching can help hold various teacher preparation programs to more comparable standards of preparation. Such data, used well, can also inform program approval and catalyze continuous improvement, ultimately increasing the availability of higher-quality programs and incentivizing candidates to choose such programs.

- Provide strong mentoring and induction programs that can strengthen novice teachers’ effectiveness and increase the likelihood of their retention in the profession. These programs can benefit schools and students while reducing shortages. These efforts are also vital pieces of the puzzle for their potential to fill in the gaps in preparation of teachers from intern and non-licensure routes.

- Bolster the state’s educator workforce data to provide data to better understand supply, demand, shortages, and their relationship to preparation, mentoring, and working conditions. Understanding where and why teachers and teacher candidates exit the pipeline is an additional policy imperative. It will be important to track whether current and future investments in high-quality preparation improve these outcomes and what is working to strengthen the state’s ability to provide a stable, diverse, well-prepared teacher workforce to all students in Texas.

Conclusion

High and climbing teacher attrition rates have exacerbated a large annual demand for new teachers in Texas. These trends have helped create systemic challenges for the Texas teacher workforce; in particular, a majority of new teachers are now hired before completing preparation. These challenges warrant close attention from policymakers. Fortunately, substantial work is already underway in Texas to address teacher shortages and stabilize the teacher workforce, but more remains to be done. A range of targeted policy interventions, guided by successful experiences in other states, can help address the key factors that influence workforce stability. These policy interventions include investing in high-quality preparation models; reducing financial barriers to entry for teacher candidates; increasing teacher compensation; supporting improvements to teacher induction and working conditions; and improving state educator workforce data.

Strengthening Pathways Into the Teaching Profession in Texas: Challenges and Opportunities (policy brief) by Jennifer A. Bland, Steven K. Wojcikiewicz, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Wesley Wei is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Charles Butt Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.