Safe Schools, Thriving Students: What We Know About Creating Safe and Supportive Schools

Summary

The report on which this brief is based summarizes research on the effectiveness of two sets of strategies to improve student safety in schools: increasing physical security and building supportive school communities. Strategies to increase physical security—such as controlling access to the building, badging staff and visitors, using security cameras and metal detectors, employing school resource officers, and arming school staff—have grown in use over time, but there is little evidence on the effectiveness of most of these. Studies have found that the presence of school resource officers has limited effects on school safety and can lead to negative student outcomes associated with increases in suspensions, expulsions, police referrals, and student arrests. Strategies to build a supportive school community in an effort to protect against factors that lead to violence include mental health supports, social and emotional learning, restorative practices, and structures that support positive developmental relationships. Multiple studies have found that these strategies benefit students, support schools, and create conditions that promote safety and reduce violence. By investing in these research-backed supports and interventions that address students’ well-being, states and school districts can help support school safety.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

A rise in the number of school shootings over time has driven increasing attention to school safety. However, shootings are not the only physical safety threat students may encounter at school. Other types of violence include sexual assault, robbery, physical attack or fights, and threats of physical attack. In addition to immediate physical harm, school violence can have long-lasting effects that undermine students’ engagement and mental health. It can also increase drug use and risk of suicide.

Although there is widespread agreement that all children and youth deserve a safe and healthy school environment, there is significant debate about how best to promote student safety. As states, districts, and schools consider policies and practices that will promote school safety, they can look to existing research to understand more about the effectiveness of proposed strategies and the potential risk of unintended consequences. Although this brief summarizes what is known about the prevalence and effectiveness of strategies to improve student safety in schools, we acknowledge that schools are not the only place where young people experience violence, and there is much to be done to ensure safety in all homes and social spaces.

Key Findings

There are two common approaches to improving school safety: increasing physical security and building supportive school communities.

Strategies Intended to Increase Physical Security

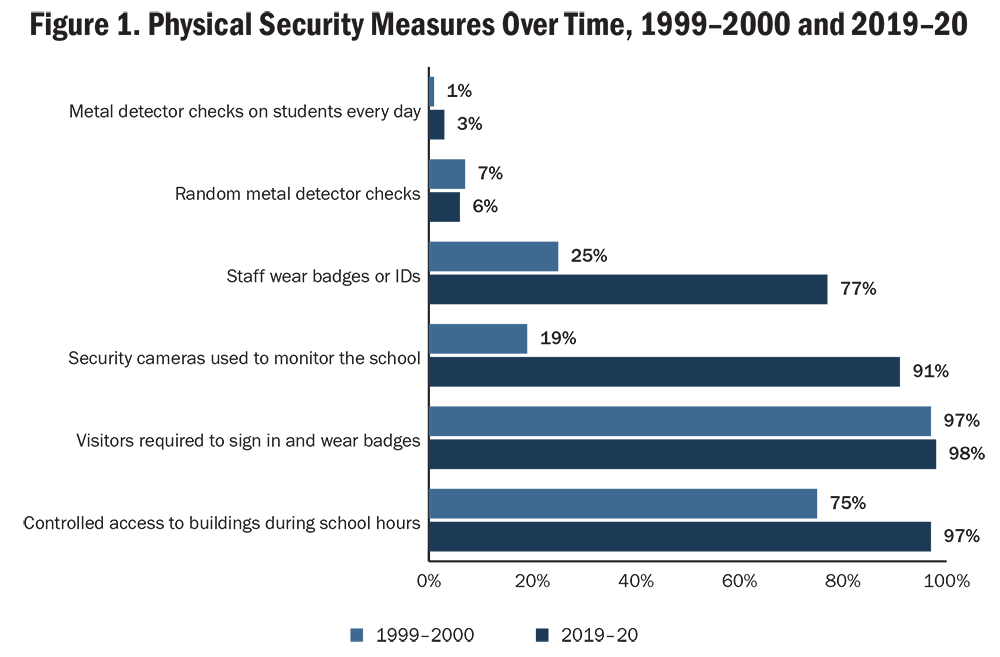

After episodes of school violence, there are often calls to “harden” school buildings (e.g., restrict building access, install metal detectors, add armed security, and arm teachers) to protect students and staff. As the frequency of school shootings has increased over the past 2 decades, so has the use of strategies for physically securing school campuses (see Figure 1). However, the evidence base for most of these strategies is not robust.

Controlling access to the building and badging staff and visitors in order to identify adults who have legitimate access to the school building have become common practices within schools. In 2019–20, almost all schools controlled access to buildings during school hours and required visitors to sign in and wear badges, and 77% required staff to wear badges. There are no studies of the impact of these measures on school safety, perhaps due to the prevalence of these practices in schools and other spaces and the relatively low cost of enacting these policies.

Security cameras are used by the vast majority of schools (91% in 2019–20), but there is no evidence that security cameras improve school safety. The one study that examined the impact of security cameras on school safety found they were not associated with reduced crime or social disturbance.Fisher, B., Higgins, E., & Homer, E. (2021). School crime and punishment and the implementation of security cameras: Findings from a national longitudinal study. Justice Quarterly, 38(1), 22–46.

Metal detectors have been proposed as a school safety measure; however, they are relatively rare in school settings: Only 3% of schools used them daily in 2020, perhaps because they come with a hefty price tag for equipment and staff. Existing evidence is sparse and does not provide support for expanding use of metal detectors. Of the two studies examining the relationship between metal detectors and school safety, one found reports of fewer weapons being carried to school; however, neither found that the presence of metal detectors reduced the number of reported threats, physical fights, or instances of student victimization in school.Hankin, A.,Hertz, M., & Simon, T. (2011). Impacts of metal detector use in schools: Insights from 15 years of research. Journal of School Health, 81(2), 100–106. A few studies have found that metal detectors are not always effective in detecting weapons and are associated with lower perceptions of school safety among students.Garcia, C. (2003). School safety technology in America: Current use and perceived effectiveness. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 14(1), 30–54; Mayer, M. J., & Leone, P. E. (1999). A structural analysis of school violence and disruption: Implications for creating safer schools. Education and Treatment of Children, 22(3), 333–356.

School resource officers (SROs) are sworn law enforcement officers with arrest powers who work in school settings: In 2019–20, 41% of elementary schools, 68% of middle schools, and 71% of high schools had SROs who routinely carried a weapon in school.U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Digest of education statistics. Table 233.70. Percentage of public schools with security staff present at least once a week, and percentage with security staff routinely carrying a firearm, by selected school characteristics: 2005–06 through 2019–20. Studies have found that the presence of school resource officers has limited effects on school safety and can lead to negative student outcomes. The largest, most rigorous study of school resource officers found that their presence increased the number of weapons detected and decreased the number of fights within schools but had no effect on gun-related incidents. However, the presence of SROs, on average, increased the numbers of suspensions, expulsions, police referrals, and student arrests—all of which can have a long-term negative impact on students by increasing disengagement, dropout rates, and incarceration rates.Sorensen, L. C., Avila Acosta, M., Engberg, J., & Bushway, S. D. (2023). The thin blue line in schools: New evidence on school-based policing across the U.S. [EdWorkingPaper No. 21-476]. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. These negative impacts were consistently larger for Black students and students with disabilities, which suggests that the use of SROs has the potential to expand gaps in educational opportunity and attainment.

Research examining the implementation of school resource officers provides some clues to help explain why their presence can lead to unintended negative outcomes for students. These include lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities and lack of training on how to effectively engage with students.Finn, P., Shively, M., Mcdevitt, J., Lassiter, W., & Rich, T. (2005). Comparison of program activities and lessons learned among 19 school resource officer (SRO) programs. Involvement of school resource officers in everyday school discipline is associated with weakened relationships between students and teachers and increased severity of punishment against students.Theriot, M. T. (2009). School resource officers and the criminalization of student behavior. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(3), 280–287.

Arming school staff has been proposed as a method of protecting students from mass shootings. There is no evidence that arming staff in K–12 schools is effective in improving school safety, and one study of school shootings found that the presence of an armed guard was associated with an increase in the number of casualties.Peterson, J., Densley, J., & Erickson, G. (2021). Presence of armed school officials and fatal and nonfatal gunshot injuries during mass school shootings, United States, 1980–2019. JAMA Network Open, 4(2), e2037394. Over the past 5 years, almost 100 incidents of accidental discharges of guns in schools have been reported, some of which have resulted in death or injury to students or staff.Everytown Research and Policy. (2019). Arming teachers introduces new risks into schools [Fact sheet].

Strategies to Build Supportive School Communities

There is a growing interest in improving school safety by building supportive school communities to protect against the perpetration of school violence. Multiple studies have examined factors that place students at risk of perpetrating violence and factors that protect against school violence. Studies examining mass shootings, school shootings, and school violence align in finding a common set of risk factors among perpetrators. In addition to ready access to guns, these include childhood trauma, mental health concerns, and prior perpetration of violence.Turanovic, J., & Siennick, S. (2022). The causes and consequences of school violence: A review. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. In contrast, when students feel welcome and connected to their school communities, they have improved mental health, academic, and behavioral outcomes and are less likely to engage in high-risk behaviors.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). CDC Healthy Schools: School connectedness. As protective factors increase, risk factors decrease.

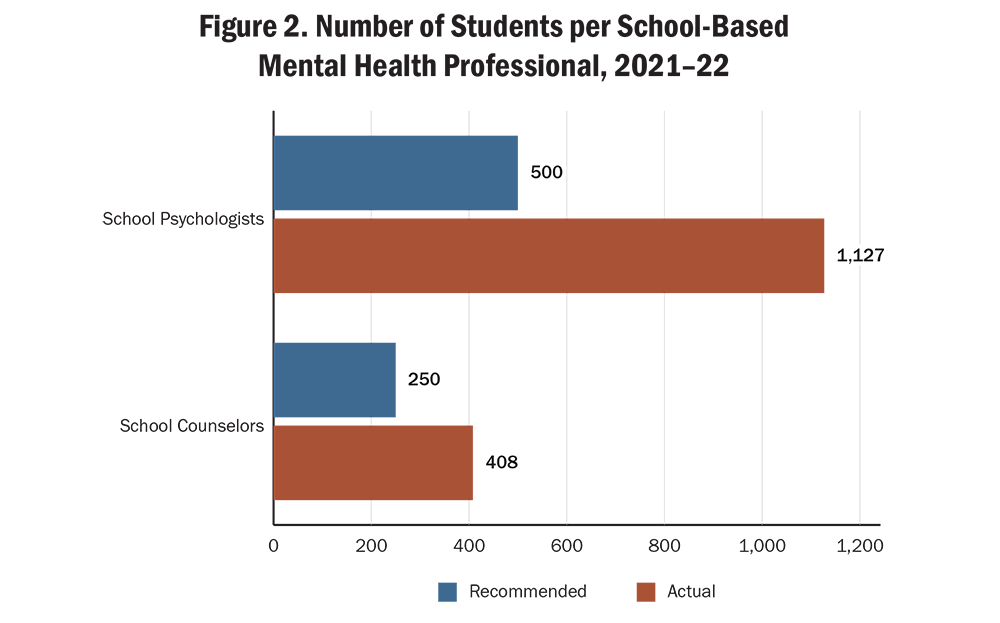

Mental health supports have been shown to benefit students and schools. Multiple studies have found that counselors reduce disciplinary incidents and disciplinary recidivism; improve teachers’ perceptions of school climate and student behavior; and increase academic achievement, especially for boys. School-based mental health services for students have been found to be effective in improving students’ mental health.Sanchez, A. L., Cornacchio, d., Poznanski, B., Golik, A. M., Chou, T., & Comer, J. S. (2018). The effectiveness of school-based mental health services for elementary-aged children: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(3), 153–165. However, schools’ ability to provide needed support is strained. On average, public schools have only 1 counselor for every 408 students and only 1 school psychologist for every 1,127 students.Carrell, S. E., & Carrell, S. A. (2006). Do lower student to counselor ratios reduce school disciplinary problems? Contributions to Economic Analysis and Policy, 5(1), Article 11; Reback, R. (2010). Schools’ mental health services and young children’s emotions, behavior, and learning. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(4), 698–725. These ratios of students to school-based mental health professionals are far above the recommended levels (see Figure 2). Only 42% of schools offer mental health treatment services.U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Digest of education statistics: Table 233.69a. Number and percentage of public schools providing diagnostic mental health assessments and treatment to students and, among schools providing these services, percentage providing them at school and outside of school, by selected school characteristics: 2017–18 and 2019–20.

Social and emotional learning is the process through which people acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions, achieve goals, demonstrate empathy, develop supportive relationships, and make responsible decisions. In 2021–22, approximately three fourths of schools used a social and emotional learning program or curriculum.Schwartz, H. L., Bongard, M., Bogan, E. D., Boyle, A. E., Meyers, D. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2022). Social and emotional learning in schools nationally and in the Collaborating Districts Initiative: Selected findings from the American Teacher Panel and American School Leader Panel Surveys. RAND Corporation. A large body of research on social and emotional learning programs finds that they help promote the development of social and emotional competencies; reduce behavior problems and emotional distress; increase rates of prosocial behavior; improve relationships with others; and increase student engagement and achievement.Greenberg, M. (2023). Evidence for social and emotional learning in schools. Learning Policy Institute. Surveys also suggest that high schools’ promotion of social and emotional skills is positively associated with students’ feelings of safety.DePaoli, J., Atwell, M., Bridgeland, J., & Shriver, T. (2018). Respected: Perspectives of youth on high school and social and emotional learning. CASEL.

Restorative practices—an alternative to exclusionary discipline practices—build community and teach strategies for resolving conflict. Studies of restorative practices and programs consistently find that they improve school safety, reduce the use of suspensions and expulsions, decrease rates of student misbehavior, and improve school climate. A 2023 study found that high rates of student exposure to restorative practices at school also increased achievement and reduced mental health challenges.Darling-Hammond, S. (2023). Fostering belonging, transforming schools: The impact of restorative practices. Learning Policy Institute. A recent large-scale study that tracked students’ experience of restorative practices found that greater use of such practices reduced disciplinary exclusions while improving achievement, student mental health, and school safety, with especially large gains for Black students and students with disabilities, who typically experience disproportionate suspension rates.Darling-Hammond, S. (2023). Fostering belonging, transforming schools: The impact of restorative practices. Learning Policy Institute. While 60% of schools reported using some form of restorative practices in 2019–20, studies confirm implementation challenges that require more intensive investments in professional development.Wang, K., Kemp, J., & Burr, R. (2022). Crime, violence, discipline, and safety in U.S. public schools in 2019–20: Findings from the School Survey on Crime and Safety (NCES 2022-029). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Sutherland, H., Guckenburg, S., Gurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated research review. WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center.

Structures that support positive developmental relationships within schools include small learning communities, advisory systems, block scheduling, looping (keeping the same teacher with a group of students for multiple years), smaller class sizes, and school–family connections. Multiple studies have found that positive, stable relationships between students and staff throughout the school can help prevent physical violence and bullying.National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments. Teachers. A major national study of more than 36,000 secondary students found that school connectedness was the strongest protective factor against school absenteeism, substance abuse, and violence.McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146. Another study found that positive relationships significantly enhanced the odds of students communicating potential threats to adults.Pollack, W. S., Modzeleski, W., & Rooney, G. (2008). Prior knowledge of potential school-based violence: Information students learn may prevent a targeted attack. U.S. Secret Service and the U.S. Department of Education.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

States and school districts have an opportunity to foster safer schools and adopt research-backed supports and interventions to address students’ mental health and well-being. The research suggests the following investments can help support school safety.

Increase student access to mental health and counseling resources. States and districts can allocate Bipartisan Safer Communities Act and federal COVID-19 recovery funds, as well as other federal, state, and local funds, to hire more school counselors and other mental health professionals and make plans now to maintain those staffing levels when one-time funds expire. They can also invest in external partnerships with community mental health providers, who can provide school-based or telehealth services for students.

Invest in integrated student support systems and community schools to connect students and families to needed supports. Integrated student supports that address physical and mental health, as well as social service needs, help create a personalized, systemic approach to supporting students. For state and district leaders, this means adopting and supporting comprehensive, multi-tiered systems of support, which provide students with universal supports for their well-being (such as advisories and social-emotional learning programs that support relationships) and include a well-designed system for adding more intensive, individualized interventions (such as counseling, tutoring, or specific services) as needed. By design, community schools integrate a range of supports and opportunities for students, families, and the community to promote students’ physical, social, emotional, and academic well-being.

Adopt structures and practices that foster strong relationships. At the school and district levels, leaders can adopt structures and practices (e.g., advisories, small learning communities, looping, allocated time to create strong school–family connections) that foster secure relationships and provide teachers time to know their students and their families well. State and district leaders can further support relationship-centered school designs by removing impediments to these structures and practices that can exist within traditional staffing allocations, schedules, and collective bargaining agreements. They can also provide time, funding, and support for schools to implement advisories and other relationship-centered school designs that promote learning and development.

Invest in restorative practices and social and emotional learning. School, district, and state leaders can support young people in learning key skills and developing responsibility for themselves and their communities by replacing zero-tolerance school discipline policies with policies focused on explicit teaching of social-emotional strategies and restorative discipline practices.

Prepare all school staff to better support student well-being. All adults working in schools need preparation and support to consistently support students’ social and emotional development, develop positive relationships, recognize students in need of greater mental health support, and enact restorative practices. States can support professional learning around student safety and well-being through revisions to educator preparation program approval standards, licensure standard competencies, and in-service professional learning and development. Additionally, states can establish guidance for the appropriate use of school mental health staff, paraprofessionals, and other school staff, as well as criteria for hiring, training, and continuous evaluation of their performance and roles. In schools employing school resource officers or law enforcement personnel, school and district leaders should ensure they have clearly defined responsibilities, avoid engagement in daily discipline, and have the training and support necessary to effectively support students.

Incorporate measures of school safety and student well-being in state and federal data collection. While there are many efforts to collect school safety data, existing sources only provide pieces of the school safety picture. A federally driven, systematic data collection effort that provides more detailed data on safety measures (e.g., roles of school resource officers), strategies to build supportive school communities, and educator practices that support positive school climate and student well-being could give researchers and policymakers a more complete understanding of what schools are doing to create safe and supportive learning environments.

Conduct equity reviews of school safety measures and their impact on discipline outcomes. Research has found that some efforts to improve school safety, such as the hiring of school resource officers, are sensitive to bias, particularly toward Black students and students with disabilities. To identify bias in implementation, schools, districts, and states can review disciplinary action data to track whether school safety measures are associated with increased use of exclusionary discipline and police referrals, particularly for Black students and students with disabilities. States and districts can also support schools in conducting equity reviews to track whether school safety measures have unintended consequences for students.

Conclusion

All children and youth deserve a safe and healthy school environment in which they can learn and thrive. With a new influx of federal funds, states and school districts have an opportunity to foster safer schools and adopt research-backed supports and interventions to address students’ mental health and well-being. The research evidence suggests that investments in increasing student access to school-based mental health services, adopting restorative practices, supporting social and emotional learning, and developing structures and practices that build positive developmental relationships between educators and students will help promote those goals.

Safe Schools, Thriving Students: What We Know About Creating Safe and Supportive Schools (brief) by Jennifer DePaoli and Jennifer McCombs is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the California Endowment and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not those of our funders.