State Preschool in a Mixed Delivery System: Lessons From Five States

Summary

As states expand access to public preschool, most do so in a mixed delivery system, meaning that state funding supports programs offered in local education agencies (LEAs) as well as non-LEA providers such as Head Start agencies, child care centers, and other settings. States face many decisions when it comes to administering programs and supporting quality instruction. This brief looks at the ways five states have approached these decisions while offering high-quality preschool at scale. While they have several commonalities, each state has also taken a unique approach, showing that there are several ways to structure a high-quality mixed delivery system. The brief concludes with recommendations for state policy.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Most states in the United States operate their public preschool programs in a mixed delivery system that serves children in local education agencies (LEAs) as well as non-LEA settings, such as Head Start agencies, child care centers, private schools, and family child care homes. A mixed delivery system has many benefits, including adding valuable capacity—in terms of both workforce and facilities—to serve children; providing families with choice in the environment they prefer for their children; and supporting small businesses. There are several challenges to operating a mixed delivery system, however, such as coordinating and supporting the participation of preschool providers across settings, from large LEAs to small private providers.

Mixed Delivery Preschool in Five States

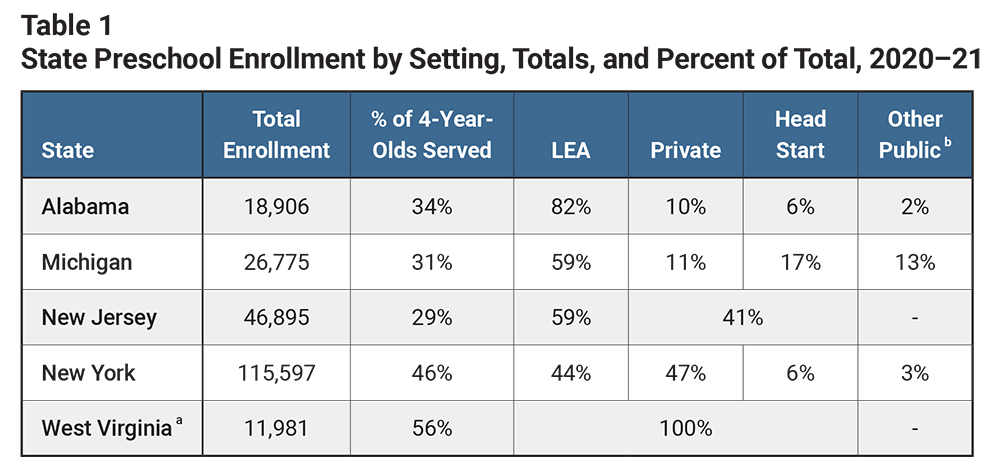

To inform state policymakers and preschool administrators as they refine their mixed delivery systems, this brief describes the mixed delivery systems of five states that have taken different approaches to supporting providers across settings, described below. All five states serve at least one third of their 4-year-old population (see Table 1) and meet at least seven of the National Institute for Early Education Research’s 10 quality standards benchmarks, indicating that they have many policies in place to support quality preschool.Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, W. S., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G., Gardiner, B. A., Jost, T. M. (2022). The state of preschool 2021: State preschool yearbook. National Institute for Early Education Research.

- Alabama’s First Class Pre-K program (FCPK) has a strong, centralized system of quality monitoring and support. FCPK reaches 34% of 4-year-olds in a full-day program, with no income eligibility requirements. State funding for FCPK is provided directly to LEA and non-LEA providers.

- Michigan’s Great Start Readiness Program (GSRP) serves about one third of its 4-year-old population and is designed to serve primarily families with low incomes. Funding flows from the state to 56 intermediate school districts (ISDs) that are responsible for distributing funding and providing professional development to LEA and non-LEA providers.

- New Jersey’s preschool expansion program, which builds on New Jersey’s Abbott preschool program, serves 29% of 4-year-olds and 16% of 3-year-olds in the state. New Jersey has high rates of non-LEA participation in public preschool, with 41% of state preschool students enrolled in non-LEA settings. Preschool funding is awarded to LEAs, which are responsible for subcontracting with and providing support to non-LEAs.

- New York’s state preschool program has two complementary funding streams: the Statewide Universal Full-Day Prekindergarten (SUFDPK) grant and Universal Prekindergarten (UPK). Together, these programs serve 46% of 4-year-olds in the state. LEAs contract directly with the state, then subcontract with participating non-LEA providers. A significant portion of state-funded slots (44%) are in New York City’s Pre-K for All program.

- West Virginia’s Universal Pre-K program (WV Pre-K) is a universal program that serves 56% of 4-year-olds in the state. State funding flows to county boards of education. At least 50% of WV Pre-K classrooms must be "collaborative," meaning that LEAs offer services in collaboration with non-LEAs. Eighty-two percent of classrooms are collaborative.

b Includes colleges, universities, and military child care.

Source: Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, W. S., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G., Gardiner, B. A., Jost, T. M. (2022). The state of preschool 2021: State preschool yearbook. National Institute for Early Education Research.

Key Considerations for a Mixed Delivery Preschool System

States face a variety of decisions when designing or expanding preschool programs in a mixed delivery system. Decisions about who oversees providers and how quality is supported have implications for the extent to which families have access to high-quality preschool options. The five case study states have similar quality standards and offer similar access to professional development across provider settings. However, they differ in how they have approached governance and oversight of LEAs and non-LEAs, from who supports non-LEA providers to how enrollment is coordinated. They also have taken different paths when it comes to program quality, including pay parity, instructional coaching, and quality monitoring.

Governance and Administration

States must determine how much oversight will rest at the state level and how much will rest at a regional or local level, addressing the following questions.

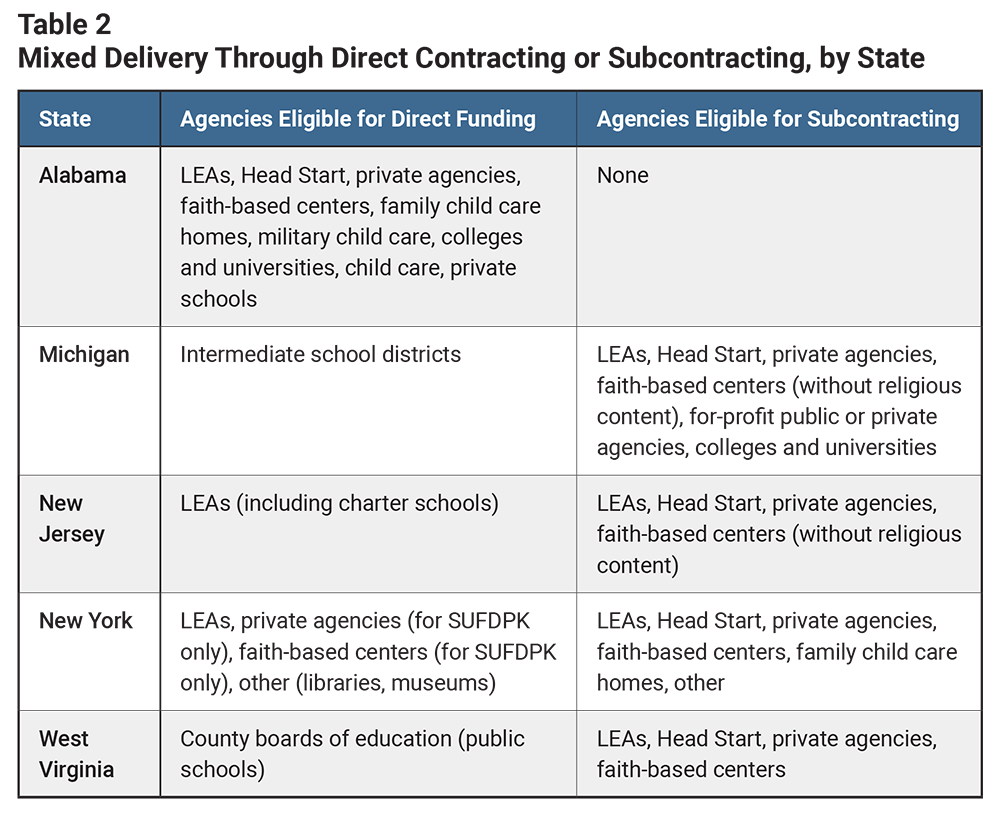

Who is responsible for contracting with preschool providers? State contracting structures affect how funding flows to providers, as well as what organization is responsible for monitoring finances and providing support to improve quality. Alabama’s FCPK has the highest level of state involvement; the state early education department allows both LEAs and non-LEAs to apply directly for state contracts through a statewide grant application process, and the state agency monitors all grantees’ finances. In New Jersey and New York, by contrast, LEAs receive state funding and subcontract with non-LEAs. Michigan and West Virginia grant funding only to intermediary agencies, which then subcontract with LEAs and non-LEAs. (See Table 2.)

Source: Learning Policy Institute. (2023).

Should legislation require the inclusion of both LEA and non-LEA providers in the state preschool system? States can signal the importance of non-LEA participation in their public preschool systems by requiring that a certain portion of children be served in these settings. West Virginia requires at least 50% of state preschool classrooms be provided through contractual agreements with community partners, including but not limited to Head Start and child care providers. Michigan requires at least 30%, and New York requires at least 10%. Both of these states exceed their legislative requirement, serving 31% and 56% of children in non-LEA settings, respectively. New Jersey does not set a quota for non-LEA participation, but some districts are required to contract with all willing and able private preschool providers in the community.The 1998 Abbott New Jersey Supreme Court decision required that the 31 urban, low-income LEAs covered by the court decision use all willing and able non-LEAs where capacity was needed to serve all eligible children. Since 2018, the state education department has approved over 200 additional LEAs to expand preschool. However, these LEAs do not fall under the Supreme Court mandate for mixed delivery.

How should states support non-LEA participation? The case study states have implemented different strategies to identify and support new providers to offer state preschool, particularly non-LEAs, which might have more barriers to participation than LEAs. Examples of these barriers include meeting teaching staff qualifications, facilities standards that differ by funding stream, and varying requirements for training in specific curriculum and assessment tools. In Michigan, ISDs provide technical assistance to non-LEA providers to help them meet the quality rating and improvement system requirements necessary to offer state preschool. New Jersey recently started offering grants to support facilities that meet state preschool standards. In Alabama, the state develops an outreach strategy to encourage providers in underserved areas to apply for state preschool funding.

How will families access public preschool in a way that is equitable? A state’s system for recruitment, outreach, and enrollment of children—often called “coordinated enrollment”—has implications for a family’s ability to find the setting that meets their needs. West Virginia requires that each county develop a unified enrollment system that ensures that all eligible children are offered a placement. Alabama simplifies applications for families by requiring all providers to participate in a statewide application process managed through an online registration platform. Michigan requires collaboration between Head Start and GSRP providers to ensure efficient use of spaces for children from low-income families. To help understand how children from different racial, ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds are accessing providers in the mixed delivery system, states can disaggregate enrollment data by child demographics and setting.

How are provider funding levels determined? Some states develop per-child state preschool funding levels that are customized to individual program needs, since program costs vary by provider type and size. In New Jersey, non-LEAs receive higher per-child rates than LEAs, since LEAs often (but not always) have larger economies of scale than do non-LEA preschool providers, and Head Start providers receive a supplement to federal funding. Alabama is one of a few states that provides funding by classroom; the state tailors funding levels to specific program needs.

Program Quality

There are several key decisions states must make when it comes to program quality, including setting quality standards, supporting continuous improvement, and monitoring quality.

What standards govern quality across the mixed delivery system? The states in this study have consistent quality standards for LEAs and non-LEAs, which could support access to a high-quality preschool experience regardless of setting. For example, all states studied require providers in both LEAs and non-LEAs to provide professional development aligned to standards and child assessments, use evidence-based curriculum, have a class size of 20 or less, and maintain a teacher-to-child ratio of at least 1:10.

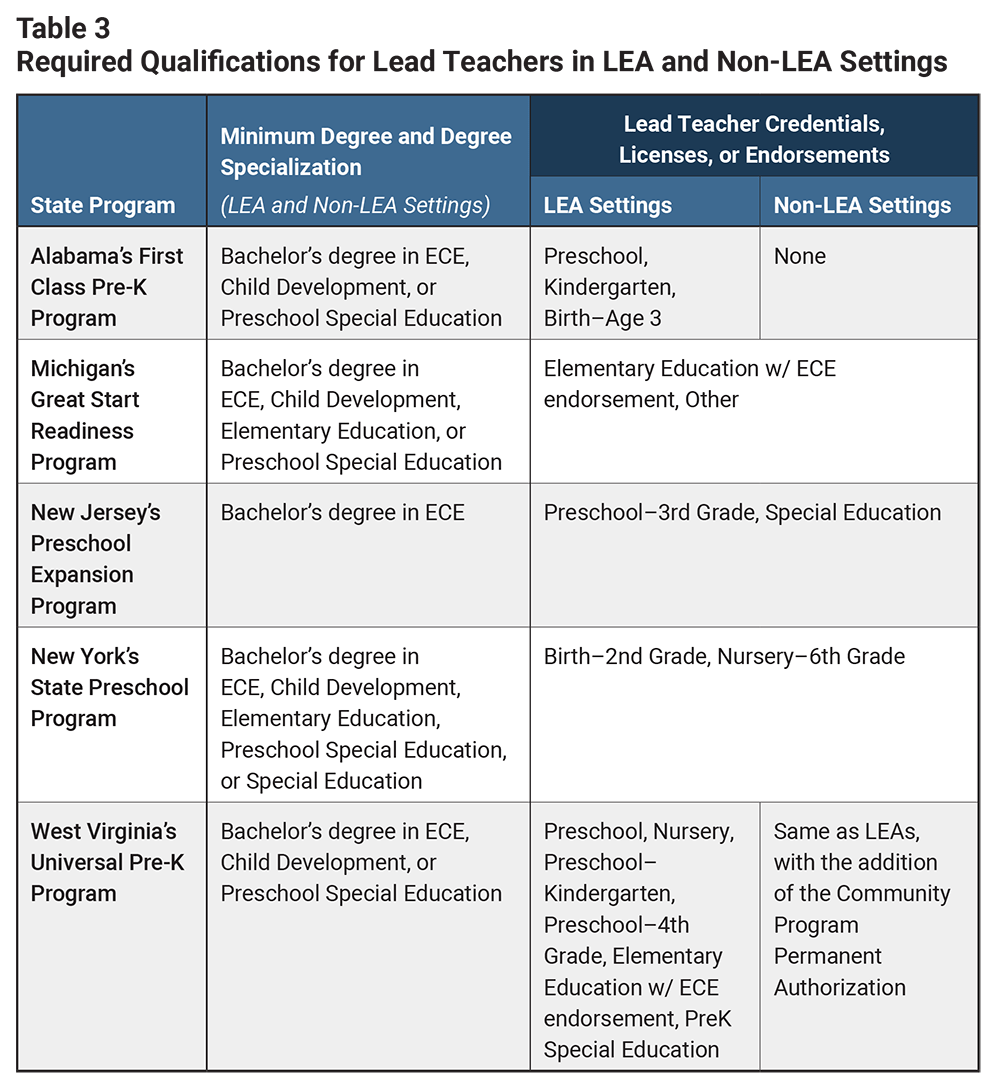

How do teacher qualification requirements vary by setting? Across LEA and non-LEA settings, all five states require equivalent qualifications for assistant teachers and require a bachelor’s degree with early childhood education (ECE) specialization for all lead teachers. In Alabama, only lead teachers in LEA settings are required to hold a teaching credential. Similarly, in West Virginia, teachers in non-LEA settings may be hired with a Community Program Permanent Authorization in lieu of a teaching credential if the provider is unable to find a fully certified teacher. (See Table 3.)

How does teacher compensation vary by setting? Nationally, preschool teachers tend to earn less than K–12 teachers, and preschool teachers in non-LEA settings earn less than those in LEAs. These wage disparities can make it challenging for preschool providers to recruit and retain qualified staff, particularly in non-LEAs. State preschool teachers in non-LEAs in New York City have achieved salary parity with preschool teachers in LEA settings through unionizing.Parrott, J. A. (2020). The road to and from salary parity in New York City: Nonprofits and collective bargaining in early childhood education. The New School Center for New York City Affairs. (accessed 08/01/22). Alabama and New Jersey address this issue by requiring that state-funded preschool teachers in non-LEA settings receive salaries commensurate with their peers in LEAs and providing funding to meet this requirement. However, both states stop short of requiring equal benefits for teachers in non-LEA settings, leaving these teachers with large differences in health and retirement benefits and in paid time off compared to their peers.

New Jersey: Mandating P–3 Teaching Certification Across Settings in State Preschool

In 1998, the Abbott v. Burke New Jersey state Supreme Court ruling established new program standards to ensure quality in state preschool programs, including a new requirement that lead teachers in all LEA and non-LEA settings hold a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education and a P–3 certification by no later than September 2004. This requirement was not a significant shift for teachers in LEA settings, who were already required to hold a bachelor’s degree and certification upon employment. However, the majority of existing teachers in non-LEA settings held only a high school diploma or Child Development Associate certificate and were deeply concerned about losing their employment under the rules of the new state preschool program.

To mitigate this issue, the state took steps to support non-LEA teachers in obtaining the required credentials while they continued to work as teachers in the state preschool program. Non-LEA teachers were given scholarship funding to obtain a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education within the time frame specified by the court, and the New Jersey Department of Education asked 2- and 4-year universities to establish satellite classrooms strategically throughout the state so that teachers would not have to travel long distances to attend classes after work. As the court-imposed deadline approached, some teachers had not yet met the requirement, despite making steady progress. Additional time was granted, and many of these teachers obtained the necessary degrees and remained as teachers in the state preschool program.

As the state preschool program expanded, and as more non-LEA teachers obtained a bachelor’s degree, non-LEA providers expressed frustration with the level of turnover among their newly certified teachers. Advocates once again approached the New Jersey Supreme Court, which ultimately required that all certified state preschool teachers in non-LEA settings must be paid comparably to their similarly credentialed peers in LEA classrooms.

The experience of non-LEA providers in New Jersey illustrates the steps a state can take to support non-LEA providers in meeting state standards and the implications of imposing uniform qualifications across settings without also addressing compensation.

Sources: Abbott v. Burke, 153 N.J. 480 (1998); Abbott v. Burke, 163 N.J. 95 (2000); Abbott v. Burke, 180 N.J. 444 (June 2004); Lobman, C., Ryan. S., & McLaughlin, J. (2005). Reconstructing teacher education to prepare qualified preschool teachers: Lessons from New Jersey. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 7(2).

How do teaching staff receive coaching and professional development? The case study states have similar requirements for teaching staff across LEA and non-LEA settings. In Alabama, coaches observe classrooms and give teachers feedback about once a month. New Jersey requires LEAs to hire at least one coach for every 20 classrooms, including in subcontracting non-LEAs. In Michigan, professional development and coaching are coordinated by the ISD, which provides coaching in each classroom at least monthly.

How do states oversee program quality? To cultivate program quality in a mixed delivery system, states need to determine how providers will be held accountable for program quality. In New Jersey and New York, LEAs are primarily responsible for overseeing and supporting quality, including in non-LEAs that receive state preschool funding. Michigan requires all state-funded preschool providers to participate in a quality rating and improvement system, which includes a twice-annual observation by an ISD-employed coach. West Virginia county collaboratives hold a contract with each participating LEA and non-LEA, detailing a system of oversight and continuous quality improvement, including annual classroom observations.

Recommendations

The states studied illustrate that, for some policy decisions related to mixed delivery preschool systems, there may be more than one correct path. However, there are six actions that states should consider taking to support a strong mixed delivery system with consistent quality across settings.

- Establish common program standards across settings so that all children receive high-quality preschool experiences. The states studied in this report have high quality standards that are aligned across LEAs and non-LEAs to ensure that families have access to quality care in a variety of settings.

- Address barriers that might prevent qualified non-LEAs from participating in the state preschool program. Non-LEAs often lack information about how to become a public preschool provider and have smaller administrative teams than LEAs to help them set up new contracts. One step some of the states in this study have taken to support non-LEA participation is to require a specific entity to identify potential providers and offer support in becoming part of the state preschool program.

- Ensure that both LEA and non-LEA providers receive ongoing support to offer and sustain high-quality learning environments, including coaching and professional development that is embedded in a continuous quality improvement system. These professional development opportunities may be offered at the state, regional, or local level and should be available to both LEA and non-LEA providers. In Alabama, the state deploys coaches regionally to provide differentiated supports based on teachers’ needs and annual assessments of quality. New Jersey requires all LEAs to provide coaching and professional development to the contracting non-LEA preschool providers in their districts.

- Ensure that program funding levels allow providers in all settings to meet high quality standards and retain qualified staff with compensation commensurate to their education and experience. The cost of meeting high quality standards can vary across settings. Funding levels impact the amount providers can pay teachers and, in turn, their ability to retain qualified staff. In most states, non-LEA teachers are paid significantly less than LEA-based teachers. New Jersey has addressed cost disparities by offering non-LEAs a higher per-child rate than LEAs, and offering Head Start providers a supplement to their federal funds to support pay parity for teachers across settings and grade levels.

- Support coordinated enrollment across the mixed delivery system to ensure family choice and provider stability. States can play a role in ensuring that preschool options are clearly communicated to families and enrollment processes are organized in a way that is efficient and equitable. Alabama’s statewide online enrollment system simplifies preschool applications for families. West Virginia requires that each county coordinate its enrollment at the county level to ensure that all eligible children are served. New York City has a single application and enrollment process for all universal preschool providers.

- Collect data and conduct research to understand families’ access to high-quality preschool in different settings. Enrollment data disaggregated by program setting and child demographics can shed light on the extent to which children from different racial, ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and abilities are enrolling in different settings. More research is needed to better understand how families choose preschool programs and the extent to which enrollment disparities reflect family preference or other barriers that should be remedied, such as availability of full-day care.

This study of five state preschool programs provides a deeper understanding of the context and implementation of mixed delivery preschool programs in these states and offers insights into how policy decisions interact to influence the mixed delivery system. Other states can use this information as they build or revise their own mixed delivery systems to provide more children with high-quality early learning experiences.

State Preschool in a Mixed Delivery System: Lessons From Five States (brief) by Karin Garver, G. G. Weisenfeld, Lori Connors-Tadros, Katherine Hodges, Hanna Melnick, and Sara Plasencia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The National Institute for Early Education Research conducted this study with support from the Learning Policy Institute.

Funding for this research was provided by the Ballmer Group, Heising-Simons Foundation, and David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Updated March 24, 2023. Revisions are noted here.