Summary

Teacher residencies represent important opportunities to address teacher shortages while improving teacher preparation. Viewed as highly effective pathways by program graduates and their employers, residencies also provide robust financial and educational support, enabling them to attract diverse candidates who stay in teaching. California has made large-scale investments in teacher residencies since 2018, and, in 2021, about 10% of all newly prepared teachers in California came through a residency pathway. This brief describes policy-relevant findings and recommendations from a set of case studies examining five of the state’s most effective programs, as judged by graduates and their employers. Included are ways in which the programs exemplify eight research-based characteristics of effective residencies. Key recommendations include strategies for designing and funding program models that are sustainable and supporting candidates so they can afford to attend.

Introduction

Teacher shortages continue to pose serious challenges for schools across the country and particularly in California. In 2022 there were more than 300,000 teaching positions in the United States that could not be filled with qualified teachers.Franco, M., & Patrick, S. K. (2023). State teacher shortages: Teaching positions left vacant or filled by teachers without full certification. Learning Policy Institute. Many states have attempted to bolster the supply of teachers by loosening credentialing requirements or implementing fast-track programs that quickly bring new teachers into the classroom. However, underprepared teachers are not only less effective, on average,Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Research on teaching and teacher education and its influences on policy and practice. Educational Researcher, 45(2), 83–91. but they also leave teaching at significantly higher rates than fully prepared teachers.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Learning Policy Institute. The resulting teacher turnover, disproportionately experienced in under-resourced schools, undermines student achievement and carries high costs for replacing teachers who have left.Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831212463813; Learning Policy Institute. (2017). What’s the cost of teacher turnover? [Interactive tool].

Some states, including California, have taken a different approach, launching teacher residencies that subsidize and support high-quality preparation for teaching in high-need shortage areas.Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Learning Policy Institute. Modeled after medical residencies, teacher residency programs are partnerships between local education agencies (LEAs) and educator preparation programs (EPPs) that require teacher candidates—or “residents”—to spend a full year in a clinical placement alongside an expert teacher while completing highly integrated coursework focused on skills for successful teaching. In paid residency programs, residents typically make a multiyear commitment to teach in the host LEA following program completion in exchange for financial support during preparation, which makes residencies particularly appealing for LEAs aiming to improve retention.

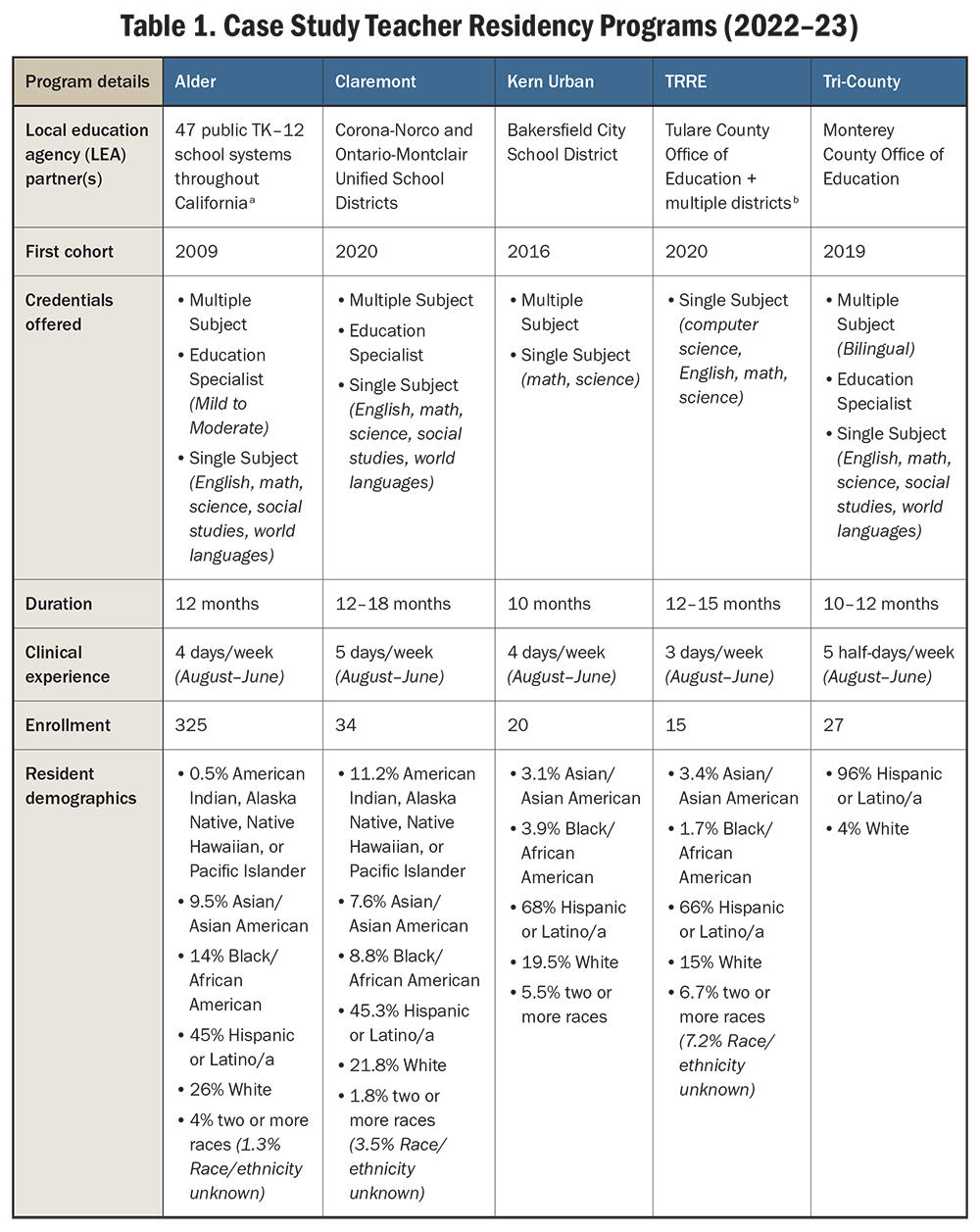

Through the Teacher Residency Grant Program (TRGP), California has made large-scale investments in residencies (see “California’s Teacher Residency Grant”). In 2021, about 10% of the state’s teacher preparation completers—more than 1,200—self-identified as having been prepared through a residency.Patrick, S. K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Kini, T. (2023). Early impact of teacher residencies in California [Fact sheet]. Learning Policy Institute. In a series of case studies, we examined five of the state’s most effective programs: the Alder Graduate School of Education Teacher Residency Program (Alder); Claremont Graduate University Teacher Education Program (Claremont); Kern Urban Teacher Residency (Kern Urban) and Teacher Residency for Rural Education (TRRE) at California State University (CSU), Bakersfield; and Tri-County Teacher Residency Program (Tri-County) at CSU, Monterey Bay (see Table 1). Of the five residencies studied, four worked with LEAs that had received TRGP funds in support of the residency. Notably, because programs and individual partnerships draw on different sources of funding, not all practices described in this brief align with TRGP grant requirements.

California’s Teacher Residency Grant

Since 2018, California has invested over $670 million to recruit diverse, comprehensively prepared teachers for high-need subject areas. Through the Teacher Residency Grant Program (TRGP), LEAs planning, implementing, or expanding a teacher residency in partnership with a California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC)-approved educator preparation program (EPP) are able to apply for grants of up to $40,000 per resident (an increase from the $25,000 maximum offered per resident at the time of our data collection). TRGP-funded programs are required to:

- address a state-designated shortage area (i.e., special education, bilingual education, STEM, transitional kindergarten or kindergarten, counseling, or other fields identified by the CTC) or diversify the local teacher workforce;

- match grant funds at 80% of the first $25,000 in grant funding per resident, which can include in-kind matching;

- provide no-cost induction to graduates through the LEA or EPP;

- group residents in cohorts;

- provide a stipend of no less than $20,000 per resident (starting fiscal year 2023–24);

- require residents to commit to teach in the sponsoring LEA for at least 4 years; and

- familiarize residents with the instructional initiatives and curriculum of the LEA.

Initial data suggest positive impacts. The TRGP Dashboard reports that, across the first three cohorts (school years 2019–20, 2020–21, and 2021–22), 758 residents completed a TRGP-funded program. Of these completers, 69% identified as people of color, 40% completed credentialing programs for teaching special education, 34% for teaching in a STEM field, and 27% for a credential with bilingual authorization. Of the 297 residents enrolled in the 2019–20 cohort, 88% were still teaching during the 2022–23 school year. Data from CTC surveys of program completers identified more than 1,200 total residency graduates in 2020–21; these completers rated their programs more favorably than those from any other pathway and reported more extensive clinical experiences and support.

Sources: California Education Code § 44415.5(d) (2023); WestEd. (2023). California Teacher Residency Grant Program dashboard (accessed 03/05/24); Personal email with Andrew Brannegan, Senior Research Associate at WestEd. (2024, March 6); Patrick, S. K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Kini, T. (2023). Early impact of teacher residencies in California [Fact sheet]. Learning Policy Institute.

b For full list of partners, see: Teacher Residency for Rural Education Project. (n.d.). School districts.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of case study program documents (2023).

Evidence of Success

For the five residencies studied, CTC program completer survey data show that more than 95% of their 2022–23 graduates rated their program as effective or highly effective, and state data indicate higher program completion and Teaching Performance Assessment pass rates than candidates from other pathways.Internal Learning Policy Institute analysis of California Commission on Teacher Credentialing data; Patrick, S. K. (Forthcoming). How preparation predicts teaching performance assessment results in California. Learning Policy Institute. Across programs, principals and other LEA leaders expressed high levels of satisfaction with residency graduate hires. The superintendent of an Alder partner LEA shared, “Our principals consistently rate the residents as higher quality than candidates coming in from other programs.” A hiring principal from a Claremont partner LEA appreciatively noted graduates’ “equity stance” and “[reflectiveness] about their practice.” Furthermore, the residencies served a disproportionately high number of candidates of color (see Table 1), contributing to teacher workforce diversity. For all these reasons, residents were considered top-tier hiring prospects by partner LEAs.

LEAs also perceived the extra classroom staffing provided by residents and the positive experiences of mentors as additional benefits of the residency model. A Claremont partner superintendent noted that in end-of-the-year surveys, mentors expressed being “more likely to stay within [the district] … because of this opportunity to grow in their own professional expertise.”

Features of Successful Residencies

Prior research identifies at least eight characteristics that successful residencies tend to share. Successful residencies (1) feature strong partnerships between the EPP and clinical placement LEA, (2) provide a full year of clinical preparation, (3) have residents co-teach alongside an expert mentor teacher, (4) tightly integrate coursework with clinical experiences, (5) place cohorts of residents in schools that model good practices with diverse learners, (6) provide ongoing mentoring and support for graduates, (7) recruit high-ability, diverse candidates to meet specific LEA hiring needs, and (8) provide financial support for residents in exchange for a 3- to 5-year teaching commitment within partner LEAs.Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Learning Policy Institute. These features were very important to the success of the five models studied.In this brief, we present only a few select examples illustrating program-specific practices and focus disproportionately on those program characteristics of greatest relevance to state and federal policymakers. For more details and examples, please see the forthcoming report that will accompany this brief.

Strong LEA–EPP Partnerships. In a high-quality partnership, the LEA(s) and EPP—and sometimes other partners, like teachers’ associations or community-based organizations—collaboratively envision, design, implement, and continuously improve the residency program. This intensive collaboration was present in the programs studied even as partnership structures varied: Kern Urban partnered with a single district, while Alder and Claremont each partnered with multiple LEAs. County offices were important partners for Tri-County and TRRE, which served multiple small, rural districts. In each case, partners built a foundation for deep and reciprocal engagement by first creating a shared vision for their work, typically by developing or clearly communicating central residency aims, and meeting regularly for collaborative decision-making, joint problem-solving, and continuous improvement.

Full-Year Residency Teaching Alongside an Expert Mentor Teacher. Unlike most traditional programs, in which candidates may experience 12 to 15 weeks of student teaching, residents spend a full academic year (36 weeks) alongside an experienced mentor teacher. In each studied program, residents’ clinical experiences span the entire arc of the school year from the first to the last day of school, and they are integrated into the school community, attending professional development meetings, family meetings, and school events. Clinical placement schedules range from 3 full days per week to 5 half or full days per week. All programs implement a gradual-release co-teaching model in which the mentor and resident collaborate and share responsibility in planning, implementing, and reflecting on lessons, with residents taking on more instructional responsibilities over time. Mentor teachers serve as teachers of record and provide daily support to residents. University coaches regularly observe, provide feedback, and advise on planning and problem-solving as needed.

Expert Mentor Teachers Who Co-Teach With Residents. High-quality mentors are key to residency preparation. Programs carefully recruit and select mentors with the experience and disposition to support residents’ learning and development in alignment with program priorities. As school-based clinical educators, mentors are compensated for their work at rates higher than those generally offered in traditional student teaching (from $1,500 to $5,000 per year, across placement sites) and are typically required to attend regular professional learning opportunities that are designed to enhance mentors’ instructional coaching, align their work with the residency’s norms and values, and build community among mentors. A Kern Urban mentor shared that the program’s monthly convenings were “vital to the mentorship.”

Coursework About Teaching and Learning That Is Tightly Integrated With Clinical Practice. The studied residencies worked to develop a coherent preparation approach across coursework and clinical experiences. They created opportunities for instructors to collaborate on the scope, content, and sequence of courses and encouraged the incorporation of district curricula and practices. Furthermore, programs hosted regular meetings between instructors, mentors, and clinical coaches to establish shared language and practices in the clinical environment. A Claremont coach noted that these meetings helped him understand candidate coursework, which improved his coaching. He explained, “I’m able to reinforce, ‘Candidate, [do] you remember [what you learned] in your class? Because I know what classes you’re taking, and you should have been doing X, Y, and Z.’” A Claremont mentor teacher noted that monthly meetings with program instructors helped her deliver clinical feedback that aligned with “the language [instructors] use to speak to their candidates.”

Cohorts of Residents Placed in Schools That Model Good Practices With Diverse Learners. By creating cohorts of residents, programs develop strong learning communities. And by designating residency placement sites that engage in equitable and effective instruction, programs can ensure that residents gain experience in sites that instantiate best practices and match their likely future teaching contexts.

Each of the five programs created cohorts of residents who studied and worked together. Residents and graduates expressed that through the cohort experience, they developed relationships with their peers and felt supported. Having residents take courses together was frequently mentioned as an effective mechanism for building community and connection, and residents described their shared courses as “safe,” “collaborative,” and “interactive.” In addition, programs sought to cluster residents at placement sites, which, as one TRRE program graduate recalled, allowed residents to “meet up throughout the day and bounce ideas off each other.” Across all five programs, cohorts met regularly for a “Resident Seminar” or “Resident Learning Community,” where resident cohorts engaged in guided reflection on their coursework and clinical experiences together.

Program graduates reported that they continue to benefit from informal cohort support even after program completion. This ongoing support was most frequently noted by Kern Urban graduates, who are typically hired in the same district by virtue of the residency’s single-district partnership. One graduate explained, “Seeing our cohort [at district induction meetings] made me feel more comfortable—I wasn’t alone in a crowd of new teachers. I knew I could reach out to any of them because they’re going through the same first year.”

Ongoing Mentoring and Support for Graduates. The studied residencies offer multiple systems to help candidates bridge preparation and employment, including assistance with meeting assessment and licensing requirements. They also support hiring processes with LEA partners, so that most on-track residents receive job offers before the end of their program. Upon hiring, graduates typically participate in LEA-sponsored induction programs, which are often housed together with LEA residency coordination in the human resources department. This strategic placement has several advantages, as it positions the residency, organizationally, in proximity to recruitment, hiring, new teacher onboarding, and professional development. As a result, residents often have preexisting relationships with key induction staff, whose familiarity with the residency allows them to design induction and professional development plans that build on graduates’ preparation.

High-Ability, Diverse Candidates Recruited to Meet Specific LEA Hiring Needs. In addition to providing strong preparation for teaching, residency programs aim to prepare candidates who meet the workforce needs of partner LEAs. In particular, they aim to recruit and prepare a more diverse group of candidates to teach in high-need fields and grades. While California has seen substantive increases in the racial diversity of teacher candidates in recent years—53% of all EPP completers identified as people of color in 2021—there continues to be wide variation in representation from different racial groups.Patrick, S. K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Kini, T. (2023). Educating teachers in California: What matters for teacher preparedness? Learning Policy Institute. Black and Native American candidates comprised only 2.6% and 0.2%, respectively, of completers and tended to have less access to preservice programs and student teaching. Residencies can help increase access for underrepresented candidates by focusing recruitment efforts or developing affinity cohorts. For example, Claremont offers a Native American Fellowship that provides full tuition and a stipend. CSU, Bakersfield has recently launched the Black Educator Teacher Residency, which has an emphasis on recruiting Black educators and developing “Afrocentric cultural competency.”California State University, Bakersfield. BETR Black Educator Teacher Residency.

Resident recruitment is informed by the staffing needs of the LEA partner, and residencies specifically recruit candidates who are pursuing credentials in LEA shortage areas. For example, TRRE’s rural partner LEAs particularly needed secondary science and math teachers, so the residency focused on these single subject pathways. At Tri-County, local districts were expanding bilingual and dual immersion programs, so the program recruited candidates looking to pursue a Bilingual Authorization.

Although LEA representatives understood residencies’ long-term potential to decrease LEA hiring needs by reducing teacher turnover, they nonetheless faced immediate staffing needs. Some LEAs met these immediate needs by hiring teachers with substandard credentials, who, despite worse retention outcomes,Ong, C., La Torre, D. Griffin, N., Leon, S., Sloan, T. … Cai, L. (2021). Diversifying California’s teaching force: How teachers enter the classroom, who they serve & if they stay. California Teacher Education Research & Improvement Network. can fill open positions as teachers of record. Another tactic, adopted by Claremont, was to develop innovative clinical models that helped to address pressing staffing needs by splitting residents’ time between mentored co-teaching—a core component of the residency model—and serving as paraprofessionals or substitute teachers. Intentional planning to place residents in these roles—or potentially even as part-time interns—with safeguards that make the experience coherent and well supported can also allow access to existing staffing budgets to supplement financial supports for residents.

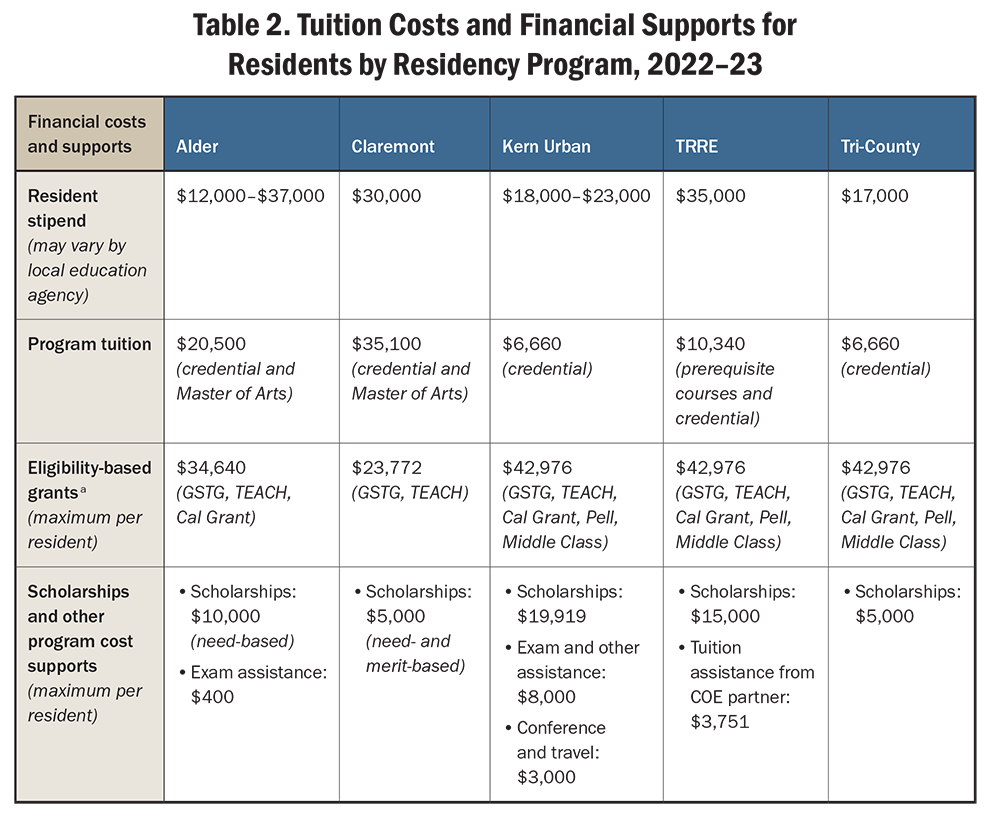

Financial Support for Residents in Exchange for a 3- to 5-Year Teaching Commitment. A major disincentive to enter teaching is the cost and debt load teachers incur for a job that, on average, pays 15% less in California than other jobs requiring a college degree.Learning Policy Institute. (2023). The state of the teacher workforce: A state-by-state analysis of the factors influencing teacher shortages, supply, demand, and equity [Interactive map]. Financial supports, particularly stipends and tuition grants (see Table 2), make comprehensive preparation possible for a broader, more diverse group of candidates. Across programs, residents shared that availability of a stipend was a top factor that attracted them. Many, particularly those with familial obligations, said they could not have afforded an unpaid preparation pathway. Stipends varied in size, ranging from $12,000 to $37,000 per year. As a condition of the stipend, residents commit to teach in a partner LEA for 3 to 5 years following program completion. Program leads reported that increasing their program’s stipend resulted in a higher number of program applicants. For example, a superintendent partner for Alder shared that after increasing their stipend from $15,000 to $37,000, the district went from around 40 applicants to more than 100. He observed, “If you can increase [the stipend] to a degree where it’s comparable to their current salary, then you’re going to get a lot more applicants, and a lot more diverse applicants.”

Note: Not all residents are eligible for all grant types.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of case study program documents (2023).

The availability of substantive financial aid through state and federal grants also helped attract candidates. Two grants were noted as highly important tuition supports:

- the Golden State Teacher Grant (GSTG) program, which provides up to $20,000 to candidates in return for a 4-year service commitment in a California priority school; and

- the federal Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) grant, which provides up to $3,772 to students completing preparation coursework, in exchange for a 4-year commitment to teach in a high-need field and school.

According to Alder’s CEO, the GSTG in particular has been a “game changer” for Alder’s program: The grant has increased “[residents’] ability to say yes to joining the program” and allowed them to graduate with a lower debt load. Between 2018–19 and 2022–23, the percentage of Alder residents taking out federal loans for their teacher preparation fell from 72% to 26%, and the average amount borrowed fell from $27,000 to $10,000. While both the GSTG and TEACH grants establish 4-year service requirements as a condition of receipt, these requirements overlap with the requirements of the state-funded residency grants. Since residents are already committed to serving in a high-need school, the stipulations of the service requirement for these other grant programs represent little additional commitment.

Although resident stipends make program participation possible for a wider contingent of candidates and increase its appeal, they make residencies more expensive to operate than traditional preparation programs. Almost all programs use significant state and/or federal grants to fund resident stipends and other program expenses. The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing’s (CTC) Teacher Residency Grant Program (TRGP) has provided an important source of funding, particularly enabling the expansion of programs that work with multiple LEA partners. Alder, as a matter of procedure, encourages all partner LEAs to apply for TRGP funds. As of 2023–24, it has 27 LEA partners using TRGP funds to support residency operations. Programs also draw essential funding for program start-up and/or expansion from federal grants, particularly the Teacher Quality Partnership (TQP) Program.

The sustainability of funding sources was a major area of concern for all studied residencies. Multiple programs were dependent on the continued availability of grants and experienced or anticipated difficulty making the transition from grant funding to more stable and sustainable funding models. For Tri-County, most notably, an unfortunately timed transition between a TQP grant and a TRGP grant caused the program to temporarily close its doors for the 2023–24 school year. Committed to providing high-quality residency pathways, Tri-County will use the TRGP funds to develop a reconstituted residency program scheduled to launch in summer 2024.

Residency leaders viewed LEA financial investment as critical to residency sustainability. Four out of five programs had LEA partners that contributed to residency operations, typically by funding resident stipends using flexible Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) dollars. Bakersfield City School District (BCSD), for example, directed $750,000 to $1.2 million of LCFF funding toward Kern Urban annually, as of 2022–23. Across programs, LEA residency leaders shared the belief that teacher residencies were worth the investment, particularly given their high retention rates. An Alder partner superintendent noted that “if done correctly, the investment is going to pay off, because in the long term you’re going to have less and less openings in hard-to-staff positions.”

Well-developed data systems and regular analysis allow programs to quantify or qualitatively describe residency benefits, which helps program champions within the LEA advocate for ongoing funding based on the LEAs’ specific priorities. For example, Kern Urban hosts regular Partnership Meetings with LEA interest holders to share data on resident demographics, retention, and other metrics and provides written reports to the BCSD board. According to BCSD’s executive director of new teacher development, these practices sustain district support and funding for the residency: “If the board and the superintendent believe in [the program], then grants or no grants, it’s going to be funded.”

Recommendations

Teacher residencies address multiple workforce challenges within the state of California. They develop localized pathways that help meet LEAs’ need for effective teachers who are credentialed in high-need subject areas, reflect the diversity of California’s student population, and are retained at high rates. When programs embody the characteristics that research suggests support resident success, these positive outcomes become more likely. The studied programs each benefited from state and/or federal investments in residency pathways, which provided essential financial support as they developed and refined their research-aligned practices. These investments have also improved access for candidates interested in teaching by making programs (and program-related costs) more affordable.

California Policymakers

This study suggests five strategies for sustaining and strengthening residencies to serve state needs:

- Maintain funding for the California Teacher Residency Grant Program and design grants to support sustainability. Funding for the TRGP is due to expire after the 2026–27 school year. As superintendents in this study attested, successful models have demonstrated strong value-add for their LEAs. Key variables for program success include (1) continued attention to adequately supporting programs’ staffing, at both the EPP and the LEA, to enable well-integrated preparation and strong mentoring, and (2) enabling programs to offer appealing candidate stipends that attract a larger, more diverse pool of residents and enable them to focus on their learning. The 2023–24 state budget increased the per-resident grant award from $25,000 to $40,000 and required, for the first time, a minimum resident stipend of $20,000. Other states go even further: For example, New Mexico requires resident stipends of $35,000 and provides $50,000 for program coordinators at each approved residency program.General Appropriation Act of 2022. H.B. 13. 55th Leg. 2nd Sess. (N.M.). Programs are meanwhile learning how to structure roles so that LEAs can contribute by employing residents as paraeducators, transitional kindergarten assistant teachers, apprentices, or part-time substitutes. As strong residencies illustrate what is possible and needed for success, policymakers can design the next iteration of the program to take advantage of these learnings to optimally leverage state and local funding.

- Continue to provide financial aid for teacher education candidates. The Golden State Teacher Grant program, which provides up to $20,000 for students enrolled in a CTC-approved teacher preparation program, is due to expire in 2025–26—or potentially earlier, given the current rate of award spending. This grant has been described as a game changer for teacher recruitment: It has contributed to a substantial increase in fully prepared teachers and teachers of color, as well as a decrease in emergency hires since 2019—thus creating more capacity and stability in the teaching force—and has decreased the debt load of residency graduates. Renewing this program, with adjustments for inflation, can support continued access for the diverse set of candidates that residencies tend to serve.

- Consider sponsoring a registered apprenticeship into teaching. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) approved the nation’s first registered teacher apprenticeship program in Tennessee. Since then, with DOL encouragement, registered apprenticeships in teaching have been launched in 31 states and U.S. territories.Melnick, H. (2024). How states can support teacher apprenticeship: The case of Tennessee. Learning Policy Institute & The Pathways Alliance. These programs allow candidates to earn while they learn: They receive pay from employers while gaining teaching skills under the guidance of a mentor teacher and taking coursework to earn their teaching credential. In 2023, the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency convened a working group to develop a Roadmap for Teacher Apprenticeships that would build on California’s “existing educator preparation pathways and investments.”California Labor and Workforce Development Agency. (2023, February 8). California developing Roadmap for Teacher Apprenticeship [Press release]. Given that the DOL-approved national guideline standards for teacher apprenticeships allow for these opportunities to be structured as residency programs or as feeder programs into teacher residencies, pursuing this option would build on state investments in residency preparation and enable residencies to leverage federal and state workforce development funding.

- Consider an ongoing, formula-funded teacher preparation and retention block grant. Such a program could be structured based on LEA need and require a local match. This would enable LEAs to continue to address teacher shortages in ways that build on their most promising strategies (e.g., residencies, classified staff teacher training programs) and respond to local contexts and needs. This could be particularly impactful for smaller or rural LEAs whose staffing needs go beyond the state-identified high-need shortage areas.

- Build technical assistance to increase residency program capacity to design and maintain high-quality sustainable models. California recently launched a Statewide Residency Technical Assistance Center, a central purpose of which is to support scaling and sustainability of residencies.California Educ. Code § 44415.7. The new center can help programs across the state learn from these successful models and develop sustainable approaches, for example by strengthening financial aid advising or helping partner LEAs tap into LCFF dollars.

Federal Policymakers

The federal government has an important role to play in financial aid for education, generally, and in solving the teacher shortage, specifically. As it has done in medicine, the federal government can make preparing to teach in high-quality programs more affordable—particularly for those who prepare to work and stay in high-need communities, as residents do.Darling-Hammond, L., DiNapoli, M., Jr., & Kini, T. (2023). The federal role in ending teacher shortages. Learning Policy Institute. Among federal actions that could make a difference are the following:

- Expand funding for the Teacher Quality Partnership (TQP) grant program. TQP grants, offered through Title II of the Higher Education Act, provided important sources of start-up funding for several studied residencies. By supporting programs through their early years, this funding gave leaders time to develop programming and plan a transition to more stable and sustainable financial models. Expanded funding for TQP grants can help more residencies similarly launch, develop, and expand their programming.

- Upgrade the TEACH grant to cover the full cost of tuition. The federal Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) grant currently provides grants of up to $3,772 to students completing coursework to begin a career in teaching, in exchange for a 4-year commitment to teach in a high-need subject in a high-poverty school. Increasing the grant amount, ideally to cover the cost of postbaccalaureate teacher preparation, can increase the attractiveness and feasibility of teacher residency programs, particularly for diverse candidates.

- Cover teachers’ monthly loan payments until their debt is retired. Existing federal loan forgiveness programs (e.g., Public Service Loan Forgiveness, Teacher Loan Forgiveness) require teachers to shoulder years of monthly payments with salaries that are lower than those of similarly educated professionals. These programs could instead be structured to have the federal government cover teachers’ federal loan payments as long as they remain in the classroom and ensure the debt is retired after 10 years of service. Such a policy could serve as an incentive for both recruitment and retention.

Successful Teacher Residencies: What Matters and What Works (brief) by Julie Fitz and Cathy Yun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.