California Community Schools Partnership Program: A Transformational Opportunity for Whole Child Education

Summary

The historic $3 billion investment in the California Community Schools Partnership Program provides an opportunity to transform schools into community hubs that deliver a whole child education. This brief examines key elements of the new law. It then lays out evidence-based principles of high-quality community schools implementation that are grounded in the four research-backed pillars included in statute and aligned with the science of learning and development. It concludes with a discussion of the technical assistance needed for high-quality implementation.

Introduction

In July 2021, California passed a historic $3 billion investment in the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP)California Education Code § 8900-8902 (2021). (accessed 09/30/21). This investment builds on an initial $45 million investment in the CCSPP for the 2020–21 fiscal year. For more information, see California Community Schools Partnership Program. (n.d.). (accessed 09/29/21).. This investment will significantly strengthen and expand community schools across the state, with a focus on schools and communities with demonstrated need. The grant funding (including both new and existing initiatives) is intended to provide sufficient resources for every high-poverty school in California“High-poverty schools” are defined in the law as schools with at least 80% of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. to become a community school within the next 5 years, located within networks of community schools supported by local education agencies (LEAs).

In addition, the 2021–22 state budget includes several large investments that—if coordinated well—stand to position districts and schools to deliver on the promise of a whole child education. These investments include funding for youth-based behavioral health, expanded learning, universal transitional kindergarten, increased staffing in high-need schools, and professional learning for educatorsCalifornia A.B. 130. (2021–2022 Reg. Sess.). Education finance: Education omnibus budget trailer bill. (accessed 09/30/21); Newsom, G. (2021). Enacted budget summary: 2021–22. State of California. (accessed 09/30/21).. Community schools are a strategy that districts can leverage to help coordinate this wide range of initiatives, as well as ongoing efforts to implement multi-tiered systems of support, social and emotional learning, and college and career readinessOrange County Department of Education. (n.d.). Guide to understanding CA MTSS. (accessed 09/30/21); California Department of Education. (2018). California’s social and emotional learning guiding principles; California A.B. 790. (2011–2012 Reg. Sess.). Career technical education: Linked Learning pilot program. (accessed 09/30/21); California Career Pathways Trust (CCPT). (n.d.). (accessed 09/30/21)..

This brief highlights how the key elements of the CCSPP align to the core features of high-quality community schools. To achieve this transformational whole child vision, community schools can serve as an organizing strategy to enrich and expand learning opportunities, connect key partners, and bring together a variety of resources (including health, mental health, and nutrition) to support students and families. When this is done collaboratively, community schools can build trust and reduce bureaucratic barriers to accessing learning opportunities and support services, especially in the highest-poverty schools and communities.

California State Funding for Community Schools

The CCSPP funding is allocated through June 30, 2028, and will support three grant types to LEAs and schools: (1) Planning grants (up to $200,000 per qualifying entity for up to 2 years of planning, allocated in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23, with the intention to provide an implementation grant upon successful completion); (2) implementation grants (up to $500,000 annually to qualified entities, for up to 5 years, to help establish new community schools or expand/sustain existing community schools); and (3) coordination grants (up to $100,000 annually per site of an existing community school, allocated beginning in fiscal year 2024–25).

Qualifying entities include district and county LEAs and schools with demonstrated needIndicators of need include 50% or more of enrolled unduplicated pupils at the LEA; as well as higher-than-state-average rates of dropouts, suspensions/expulsions, child homelessness, foster youth, or justice-involved youth., as well as county behavioral health agencies, federal Head Start/Early Head Start programs, and child care programs within public institutions of higher education that commit to operating in partnership with at least one qualifying LEA. The statute prioritizes funding for applicants that have significant proportions of high-need students, along with several other competitive prioritiesApplicants with 80% or more of enrolled unduplicated pupils will be prioritized for funding. Additional competitive priorities include demonstrated need for expanded access to integrated services; involvement of pupils, parents, school staff, and cooperating agency personnel in identifying needs and planning support services; committing to providing trauma-informed health, mental health, and social services for pupils within a multi-tiered system of support; committing to providing early care and education services for children birth to age 5; identifying a cooperating agency collaboration process; and identifying a plan to sustain community school services after grant expiration..

Grants can cover staffing costs (including community school coordinators); service coordination and provision; community stakeholder engagement; ongoing data collection; and training on integrating school-based pupil supports, social-emotional well-being, and trauma-informed practices. Additional funding will be allocated through a competitive process to establish a network of at least five regional technical assistance centers operated through LEAs, with preference given to LEAs that commit to partnering with institutions of higher education or nonprofit community-based organizations.

Overview of the California Community Schools Partnership Program

The CCSPP is well aligned with existing research and provides an opportunity to act on a bold vision for transforming schools. The definition of community schools in Education Code Sections 8900-8902 is aligned with research identifying four pillars of community schoolsCalifornia Education Code § 8900-8902 (2021); Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Learning Policy Institute.. Specifically, community schools are defined in statute as public schools with “strong and intentional community partnerships ensuring pupil learning and whole child and family development,”California Education Code § 8900-8902 (2021). including the following features:

- Integrated student supports, which can help students succeed by meeting their academic, physical, social-emotional, and mental health needs. Statute defines this as the “coordination of trauma-informed health, mental health, and social services,” including case-managed health, mental health, social, and academic supports benefiting children and families. Examples in the law include health care, dental services, prenatal care, trauma-informed mental health care, educator training on the impact of trauma and toxic stress, family support and education, academic support services, counseling, and nutrition services.

- Enriched and expanded learning opportunities that include academic support and real-world educational experiences (e.g., internships and project-based learning). Statute refers to these opportunities as both “extended” and “expanded” learning and defines them as including “before and after school care and summer programs.” Throughout, the statute recognizes that addressing whole child learning will have implications for the instructional practices within the school day as well.

- Family and community engagement, which involves actively tapping the expertise and knowledge of family and community members to serve as true partners in supporting and educating students. Statute defines this as including “home visits, home-school collaboration, [and] culturally responsive community partnerships.”

- Collaborative leadership and practices for educators and administrators that establish a culture of professional learning, collective trust, and shared responsibility for outcomes in a manner that includes students, families, and community members. Statute defines this as “professional development to transform school culture and climate, that centers on pupil learning and supports mental and behavioral health, trauma-informed care, social-emotional learning, restorative justice, and other key areas related to pupil learning and whole child and family development.”

Key Principles of Well-Implemented Community Schools

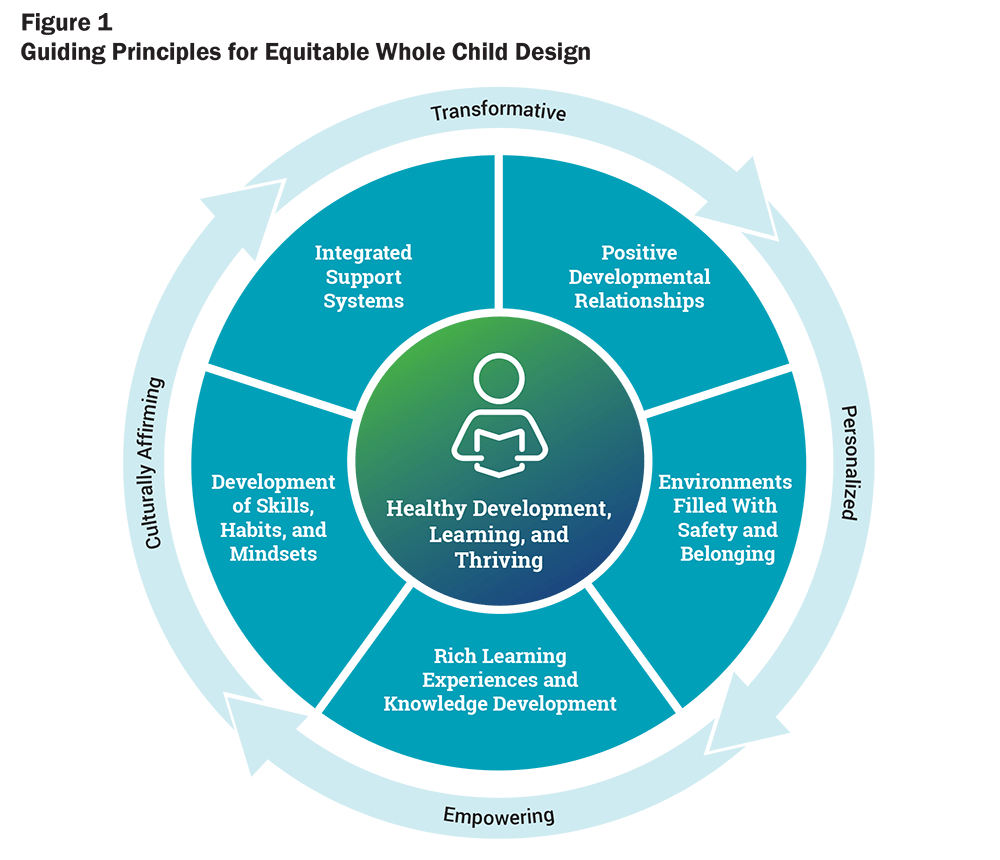

When implemented well, community schools are guided by principles for equitable whole child practices grounded in the science of learning and developmentCantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337; Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140; Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36.. These principles place integrated student supports in the context of positive developmental relationships; an environment of safety and belonging; rich learning environments; and explicit development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills and mindsets that contribute to academic and life success (see Figure 1 and the Design Principles for Schools playbook for more information). This approach prioritizes the full scope of children’s development across multiple domains—including academic, physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and emotional learning—by addressing the distinctive strengths, needs, and interests of students as they engage in learning. It is designed to support the welfare of the whole child and is embedded in community school standards and practicesKimner, H. (2021). Practices of a healing-centered community school. Policy Analysis for California Education. (accessed 9/27/21); Coalition for Community Schools. (2017). Community school standards; Advancement Project California, Association for California School Administrators, Attendance Works, California Association of African-American Superintendents & Administrators, California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, et al. (2021). Reimagine and rebuild: Restarting school with equity at the center.. A description of Mendez High School—part of the Los Angeles Unified School District community school cohort funded by the CCSPP—shows how these principles can reinforce each other in real life.

I. Integrated Student Supports

Integrated student supports can address multiple domains of whole child development through a trauma-informed and assets-based lens. These supports include the availability of high-quality tutoring and mentoring, counseling, and student support teams, along with health, mental health, and social services provided by a combination of district and school staff and community partners. Services and opportunities should be identified based on findings from an inclusive comprehensive needs and assets assessment process and should be offered in a manner that is culturally and linguistically responsive.

The foundation for effective student support—and powerful learning experiences—is the presence of positive developmental relationships, in which attachment and caring are combined with adult guidance that helps students learn skills and grow more competent and confident. Effective community schools are relationship-centered, meaning that the work to support students, families, and educators rests on and is bolstered by a web of trusting and respectful relationships between and among these core members of the school community.

Positive relationships help to establish restorative learning environments that foster a sense of emotional safety and belonging. Such environments can strengthen students’ confidence and motivation to take chances and deeply engage in school and learning, which is necessary both to address trauma and to avoid creating school-imposed trauma. To establish these environments, schools and classrooms should function as learning communities with norms, routines, and high expectations that demonstrate cultural sensitivity, communicate the worth of each student, and are co-created by staff and students. (See this report on Social Justice Humanitas Academy, a community school in Los Angeles, for an example.) Restorative environments can help to increase students’ sense of ownership and responsibility and can provide consistency and predictability. Doing so can reduce anxiety and, ultimately, support student agency and engagement. In contrast, negative stereotypes and biases, bullying or microaggressions, punitive discipline practices (which have a disproportionate impact on students of color and students with disabilities), and other exclusionary or shaming practices create anxiety and toxic stress, erode trust, and undermine student success.

Relevant structures and practices include:

- Structures that enable the development of continuous, secure, and trusting relationships and allow teachers to know students well, such as small learning communities, advisory systems that provide a family unit and adult advocate for every student within secondary schools, teams of teachers who share the same group of students in secondary schools, and looping with the same group of students for more than 1 year.

- Restorative practices that address trauma and reduce exclusion by building community, enabling reflection, and teaching social-emotional skills (e.g., community circles for discussing feelings and experiences, places where students can defuse and reflect, processes for explicit conflict resolution, and trauma-informed practices), along with support to help educators implement these practices and connect students to the services they need.

- Interdisciplinary teams/systems—including Coordination of Services Teams (COST) and multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS)—to ensure that all students and families have access to well-coordinated supports that focus on both prevention and early intervention, as well as effective treatment (see examples from Alameda County and Los Angeles County). These approaches can engage school staff, families, and community partners in meeting regularly to assess students’ strengths and needs, connect students with appropriate services, and track their learning progress over time.

- Supports and opportunities based on student needs and input from the full school community, including students, families, teachers, and staff. This can include supports offered in before- and after-school care such as food, nutrition services, social-emotional strategies, and enriching extracurriculars funded by a new investment of $1.75 billion in 2021–22 that will grow in coming years.Darling-Hammond, L., Pittman, K., & Peck, J. (2021, July 16). Better, broader learning: California education policymakers prioritize bolder expanded learning opportunities [Blog post]. (accessed 10/07/21). (See community school supports available for newcomers at Oakland International High School, as an example.)

- A full-time community school coordinator or director who provides essential leadership in managing key features, functions, and processes at the school site. An effective coordinator is a member of the school’s leadership team and facilitates communication among the principal, teachers, other school staff, community partners, and families. This includes ensuring that students, families, and educators are engaged in identifying culturally and linguistically responsive supports, services, and opportunities, as well as learning about additional supports as they become available. The coordinator can also lead strategic planning and mapping of school and community assets and needs, as well as develop and oversee partnerships—including facilitating data collection, sharing, and analysis.

II. Enriched and Expanded Learning Opportunities

Enriched and expanded learning opportunities include in-classroom instruction that offers rich learning experiences, as well as extended learning time and opportunities that support academic growth along with social, emotional, and physical development.

Rich learning experiences are focused on the development of deep understanding; they center students by building on their individual strengths and experiences, and they make disciplinary content meaningful and accessible. These learning experiences also provide culturally and linguistically responsive instruction and enable the development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills. Because the brain is cross-wired and functionally interconnected, social, emotional, and cognitive skills are interrelated. These skills can (and should) be taught, modeled, and practiced in a way that is integrated across all subject areas and across all settings in a community school.

These kinds of experiences should infuse both in-classroom instruction and robust extended learning opportunities that help address critical equity issues by providing additional time and focused attention to students’ learning needs and interests. Early learning programs that are mentioned in statute represent another important expanded learning opportunity and are especially important in addressing opportunity gaps. The most impactful expanded learning opportunities are connected to the school’s curriculum and result from close collaboration between the school day staff and expanded learning program staff around shared goals and strategies that are grounded in the science of learning and development.

Relevant structures and practices include:

- In-classroom instruction that supports inquiry-based learning and problem-based learning around rich, relevant tasks that are culturally and community connected and collaboratively produced (as UCLA Community School and as MLK Middle School in San Francisco have done). Educators can make these instructional approaches accessible through language scaffolds and linguistically sustaining practices, culturally responsive pedagogies, and Universal Design for Learning approaches. In-class instruction can also provide opportunities for students to share their experiences, interests, strengths, and readiness (e.g., learning surveys and student reflections) so that teachers can personalize instruction and understand what students need.

- Explicit development of social-emotional and cognitive skills and mindsets that help students become engaged, effective learners, including curricula and dedicated time that enable students to explicitly learn and practice valued skills (e.g., collaboration or conflict resolution). Opportunities and routines during everyday instruction and school activities can reinforce these skills and mindsets, including supports for growth mindset and interpersonal skill development. Educators can also provide scaffolds to support executive functions like planning, organizing, implementing, and reflecting on tasks.

- Before- and after-school and summer programs that reinforce this rich learning and are intentionally designed to meet student and community needs in a warm and caring environment; are of sufficient duration to make an impact; and provide high-quality, meaningful learning opportunities. Such programs include stable, well-trained staff; a student-centered curriculum that complements the learning taking place during the typical school day and year and offers enriching and engaging extracurriculars, such as art classes and physical activities; and strategies to ensure consistent, stable participation by students. California’s substantial and ongoing funding increase for expanded learning can support the implementation of these programs.A new investment of $1.75 billion in 2021–22 will grow to $5 billion over the next 4 years. See Darling-Hammond, L., Pittman, K., & Peck, J. (2021, July 16). Better, broader learning: California education policymakers prioritize bolder expanded learning opportunities [Blog post]. (accessed 10/07/21).

- Accelerated learning programs, including tutoring and small-group supports within and beyond the school day, which support essential curricular standards and the learning activities developed to achieve those standards. Such programs employ well-prepared staff and invest in staff capacity-building. They also provide consistent opportunities for engagement and build positive relationships among students, program staff, and teachers.

- Early learning programs that offer curriculum, instruction, and assessment that are developmentally appropriate; culturally and linguistically affirming; and supportive of individual talents, interests, and needs. These programs should also have a well-qualified and well-supported workforce that enables small student–teacher ratios.

III. Family and Community Engagement Practices

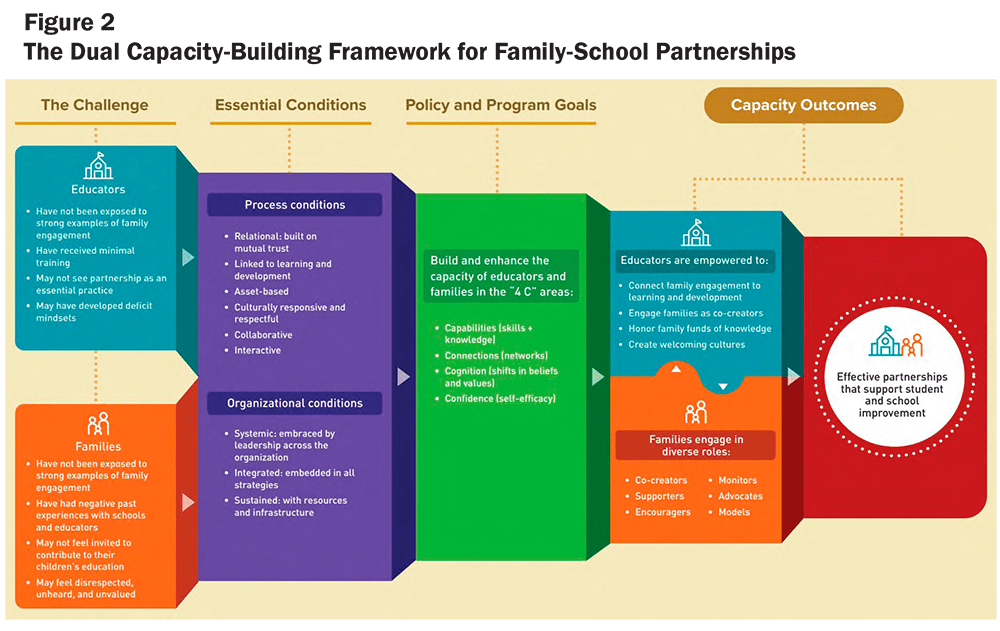

Family and community engagement practices should be centered on relationship-building and shared decision-making between families and educators so that schools and families are supporting children together in culturally affirming, mutually reinforcing ways. As presented in Figure 2, effective partnerships are asset-based, built on trust and respect, focused on student learning, and fully integrated into the everyday functioning of the school and the overall instructional approach. This framework builds the capacity of both families and school staff to engage in partnerships.

Family and community engagement activities include partnering with parents and other family members to support each and every child’s success. This involves offering courses, activities, and services for parents and community members, as well as creating structures and opportunities for shared leadership. With these inclusive and collaborative practices in place, families and community members, for their part, feel welcome, supported, and valued as essential partners.

Relevant structures and practices include:

- Flexible time built into educators’ schedules for home visits, family-student-teacher conferences, and other regular communications between home and school that are designed to be accessible to families. Educators should also have access to professional development regarding proactive, one-to-one, asset-based connections between families and educators (see Parent Teacher Home Visits for an evidence-based example).

- Family liaisons that help educators and the community school coordinator maintain good communication and connection with families at the site, including, but not limited to, communication in the languages spoken at the school and at home.

- Knowledge-building for both staff and families that enables stronger relationships. For example, staff can come to understand the community more fully through purposeful learning opportunities. (For an example, see a description of the community walks at Oakland International High School, a community school in Oakland Unified.) Meanwhile, parents can better understand their children’s school experience through opportunities to learn about such things as what children are studying, how to build a relationship with the child’s teacher, reclassification for English learners, A-G graduation requirements, and understanding the California School Dashboard.

- Ongoing courses and trainings for families on relevant topics such as English or other language classes, computer training, and GED support, as well as leadership development and capacity-building opportunities for parenting and families’ ability to negotiate the educational system with and for their child.

IV. Collaborative Leadership and Practices

Collaborative leadership and practices can provide professional development for educators and administrators on whole child educational practices, as well as structures and practices to enable shared decision-making at the school site that includes students, families, and community partners. The principal and school leadership team play an essential role in establishing a culture of collaborative leadership, including by working with the community school coordinator, partners, and staff to actively integrate students, families, and community partners into the school community, its functions, and its decision-making processes.

An important element of collaborative leadership is having a shared sense of accountability backed by a system of continuous improvement that involves the whole school community. This process is cyclical in nature and can begin with an inclusive assets and needs assessment process built with student, family, and educator input. The assessment can lead to the identification of mutually agreed upon priorities, programs, results, and indicators and, accordingly, tracking of relevant student, school, and community data. By continually revisiting the results and indicators and adjusting as needed, the school community can maintain a culture of continuous improvement and shared accountability. Where appropriate, collaborative planning processes may be integrated into Local Control and Accountability Plan consultation and development.

Individual community schools are more likely to be successful and sustained when there is strong support and infrastructure in place for collaboration at the system or district level. This requires having an administration and funding strategy that strengthens shared responsibility for supporting the community school (and the districtwide and communitywide initiative) and its relevant programming. Most community schools blend and braid federal, state, and local funding sources. This can include general education, early education, mental and physical health, special education, public safety, and public health dollars. The CCSPP-funded community input, needs assessment, and planning efforts can be leveraged to coordinate the significant amounts of one-time funds that districts are juggling, including federal recovery funds (such as from the American Rescue Plan Act), as well as state investments in youth behavioral health, expanded learning, early childhood education, and other related initiatives.

Relevant structures and practices include:

- Professional development for educators and administrators to “transform school culture and climate [and] center pupil learning” that is focused on key teaching and learning practices (e.g., social-emotional learning, restorative practices, culturally and linguistically responsive instructional practices). This professional development should incorporate active learning opportunities, support collaboration, model effective practices, provide coaching and expert support, offer opportunities for feedback and reflection, and be sustained in duration—all elements of effective professional development.Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

- Collaboration structures that support shared learning and build trust within the school community. This includes joint trainings for k–12 school day staff and expanded learning or early learning program staff (e.g., daytime and after-school teachers or all preschool-through-2nd-grade staff). Staff from expanded learning and early learning programs not only benefit from ongoing training and support, but also can share knowledge, expertise, and strategies in these sessions, given that they often live in the same communities and share the same backgrounds as the students they serve. Collaboration structures can also include time, protocols, and tools for asset-based connections that build trust between families and educators to achieve shared practice around a developmental approach to learning (e.g., home visits, student-teacher-family conferences).

- A site-based leadership team (the School Site Council or a separate body) that is well-facilitated and representative of the school community, including families, students, community partners, unions, the principal, the community school coordinator, teachers, and other school staff. This team can guide collaborative planning efforts and oversee the implementation of programs and services, from needs assessment and asset mapping to vision, goal, and priority setting; budgeting decisions; gathering and understanding data; and monitoring progress, measuring impact, and making critical adjustments as needed along the way. Students and families should have access to leadership opportunities, training, and support to engage as full partners in site-based decision-making. This can occur through the school (see decision-making structures at UCLA Community School and the Student Steering Committee at Social Justice Humanitas Academy for examples) and can involve community-based organizations (see the foundational partnerships at Mendez High School for an example).

- Shared goals, plans, and data—collaboratively developed with input from students, families, staff, and community partners—that are integrated into the school’s regular planning efforts and are based on a shared vision of student success. The shared plan should include data on school and community indicators, as well as evidence-based programs and practices to achieve desired results. There should be a process in place for regularly collecting and analyzing student data; experiences of students, families, and staff (such as California Healthy Kids Survey data or other school survey data); participant feedback on available programs and services; and data on a range of outcomes to assess program quality and identify opportunities for improvement.

- Collaborative structures at the system and/or district level to help create a cohesive and effective communitywide initiative. This includes efforts to un-silo and support cross-departmental collaboration within district or county offices, as well as building collaborative infrastructure and capacity between the county, district, schools, other governmental agencies, community, and formal community partners. A systems-level strategy can also help to identify funding streams and other resources across partner agencies (including district, city, and county) to be tapped and possibly repurposed to support community school programming. This may include building a district-level plan to utilize school-based Medi-Cal funding programs to help pay for coordinating activities.

Technical Assistance Considerations

Lessons from the field emphasize the importance of technical assistance (TA) for supporting high-quality implementation of community school initiatives. This can include professional development and coaching, support for strategic planning, and partnership development that brings resources to schools (e.g., direct staffing, service provision, and funding). Examples of TA for community school initiatives in Alameda and Los Angeles counties can be found here. Cross-sector partnerships at the county level can bring a comprehensive set of resources to local schools, especially when strengthened by a shared vision and clear agreement (e.g., a memorandum of understanding). In addition, New York state has funded regional TA centers for community schools that offer professional development for practitioners; site visits to provide in-person coaching; a database of community partners, programs, and resources; and regionwide communities of practice to share promising practices and engage in collective problem-solving.

The CCSPP funding includes a $142 million set-aside for a minimum of five regional TA centers that will be awarded to LEAs and community partners. This is a similar structure to the Healthy Start grant program, which was funded from 1992 to 2006 in California. TA for Healthy Start was offered by 11 regional providers with coordination through the Healthy Start Field Office, housed in the education department at the University of California, Davis. Grantee cohorts met regularly within regions and statewide. Focus groups of 12 districts with the most enduring Healthy Start initiatives named the importance of TA as key to their success, along with capacity-building for family engagement. Given the importance of a central coordinating role in the Healthy Start example, regional TA providers for the CCSPP would likely benefit from similar support. Furthermore, it is important to consider the capacity of TA providers and their community-based and higher education partners to support LEAs (including county offices of education and districts) and schools in implementing the key features described above.

Conclusion

This is a pivotal moment for California education. The CCSPP funding, along with additional federal and state investments, has the capacity to transform schools into student- and family-centered community hubs that provide a whole child education. Careful attention to evidence-based implementation principles, along with strong technical assistance, will play a key role in realizing this vision.

California Community Schools Partnership Program: A Transformational Opportunity for Whole Child Education (policy brief) by Anna Maier and Deanna Niebuhr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this project was provided by the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation. Core operating support for the Opportunity Institute is provided by the Stuart Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the California Community Foundation. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.