Social Justice Humanitas: A Community School Approach to Whole Child Education

Summary

Social Justice Humanitas Academy in Los Angeles Unified School District is a teacher-led community school that advances student learning and development through its mission to support students on their journeys toward self-actualization, social justice, and postsecondary success. To do this, the school centers whole child practices and maintains a community school design that cultivates a supportive and inclusive learning environment, engages students in social and emotional development and student-centered pedagogical strategies, and provides access to integrated systems of supports that enable learning and well-being.

The report on which this brief is based can be found online at https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sel-case-study-humanitas.

There’s no point in doing great work if you’re not a good person and you’re not treating those around you well and looking out for their welfare.Gilberto Ochoa, SJ Humanitas alumnus

Gilberto Ochoa learned this lesson while attending Social Justice Humanitas Academy (SJ Humanitas), a teacher-led community school that he graduated from in 2014, which serves 9th- through 12th-grade students in Los Angeles. He described how this message deeply influenced his work ethic and his professional life: “I’ve taken that into everything that I’ve done as a professional.… That was my motivation.”

Gilberto’s drive to do great work and be a good person led him to study public health while at the University of California, Berkeley. According to Gilberto, the idea of being able to apply his learning and “shape the future health” of his community guided his decision to choose public health as his career path

For Gilberto, experiences at SJ Humanitas were also instrumental in preparing him to get to and through college. Gilberto remembers his former principal, Mr. José Luis Navarro, calling attention to the uneven playing field in a way that helped him navigate college. Navarro described it as “going into a fight with our hands [tied] behind our backs” and noted that Gilberto would likely be sitting in classes where “the person next to you [has parents who] are physicians or professors.” Gilberto began to understand the systemic disadvantages and barriers that he would face and how he would have to diligently work to excel in a college environment.

Although it was a tough message, Gilberto recalls that it was delivered with care. Gilberto remembers many ways in which SJ Humanitas staff embodied the stance of caring that is at the core of the school’s ethos and describes lessons at SJ Humanitas as “helping [him] build empathy and connect with people at a deeper level.” Lessons exposed him to an existential perspective that encompassed history and the human experience, including suffering. Gilberto carries with him this recognition of a common, shared humanity. He says, “People are all battling their own things, their own struggles. I’ve taken that [sense of care] everywhere I go, and it’s really helped me be intuitive and be able to connect with people really well.”

Note: The student’s name has been changed.

SJ Humanitas is a public high school located in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley. It was designed by teachers and envisioned as a teacher-led community school—a student-centered learning environment in which teachers serve as key decision-makers, leaders, and learners. Their vision, which they actualized with partners through the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) Pilot School initiative, was to create a school that would not only be a place of learning, but also be a resource for the community. To do so, they designed a school that would bring together community resources, incorporate collaborative structures, and support students on their pathways to postsecondary success and self-actualization.

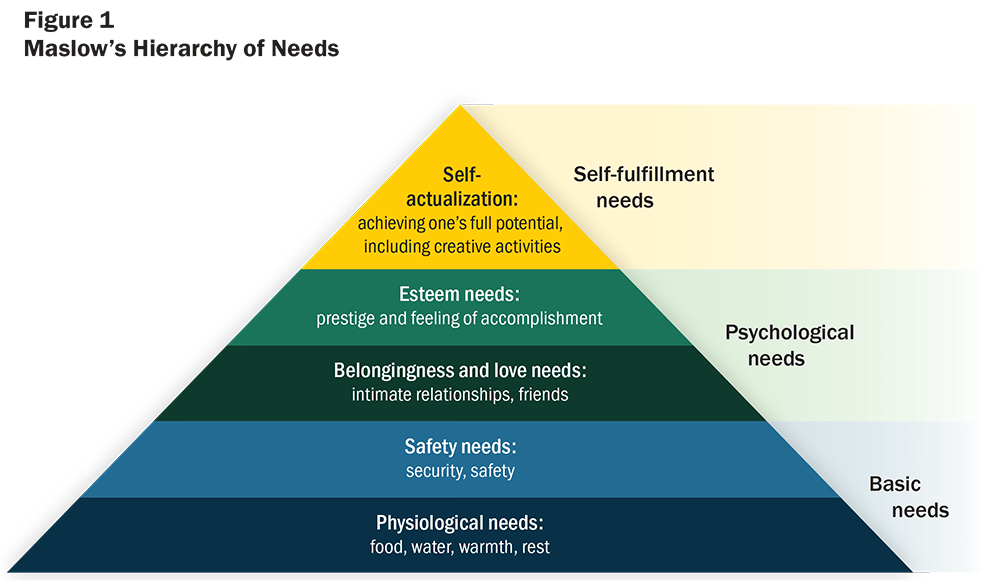

The school’s founding principal, Jose Luis Navarro, explained that SJ Humanitas’s mission is “to achieve social justice through the development of the complete individual. In doing so, we increase our students’ social capital and their humanity while creating a school worthy of our own children.” As reflected in the community school’s name and mission, social justice is deeply embedded in its fabric. Educators also emphasize the idea of self-actualization, or becoming the best version of oneself. This core value is based on Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Figure 1), which SJ Humanitas administrators, educators, and students frequently reference. With these commitments, SJ Humanitas views student growth holistically and therefore strives to support students’ academic, social, and emotional needs.

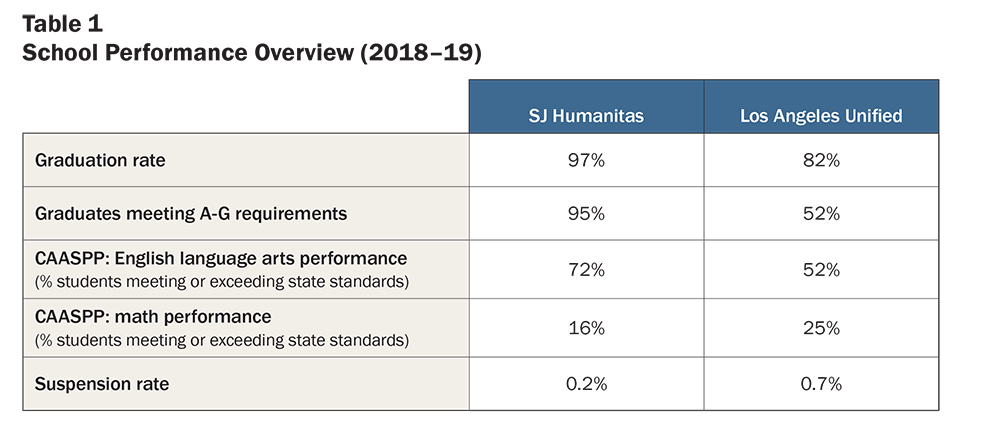

Over its 10-year history, SJ Humanitas has supported the success of its distinct student population. SJ Humanitas serves 521 students, 96% of whom are Latino/a and 7% of whom are identified as English learners. Of the total student body, 93% are identified as economically disadvantaged, which represents a larger percentage than the district average. Despite serving a more disadvantaged population, SJ Humanitas outperforms its counterparts in LAUSD on a number of measures. In 2018–19, 97% of SJ Humanitas students graduated from high school, compared to 82% in the district, and 95% of students completed the series of college preparatory courses—the “A-G” course requirements—required for eligibility to California’s public university system, which nearly doubled the district rate. Based on administration of the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP), a standardized assessment aligned to the Common Core State Standards, 72% of SJ Humanitas students met or exceeded standards for English language arts, compared to the district average of 53% of high school students (see Table 1). While outperforming LAUSD averages in these areas, the school still has some areas for growth, particularly in advancing students’ mathematical knowledge and skills.

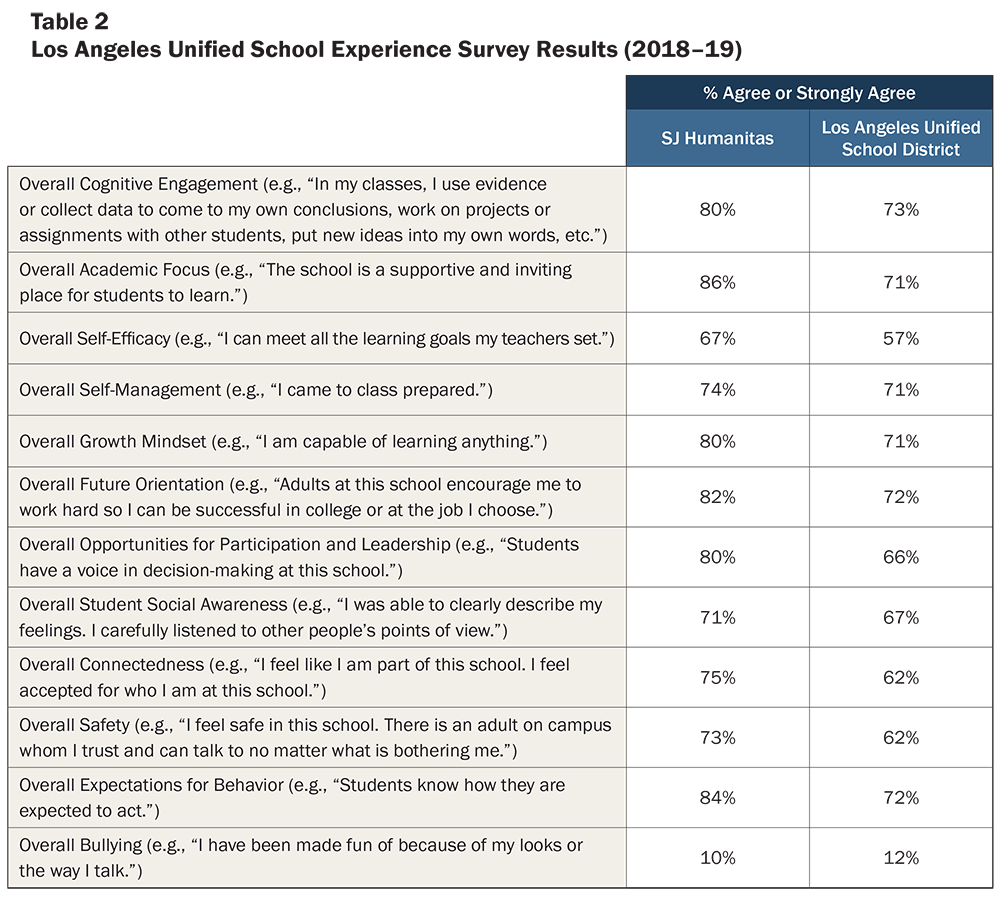

In addition, LAUSD School Experience Survey data suggest that SJ Humanitas students demonstrate important competencies—such as holding a growth mindset, feeling connected to their school, and being socially aware and self-efficacious—at higher rates than their peers in other district schools (see Table 2). Further, SJ Humanitas students characterize their school community as safe and supportive at rates higher than their district counterparts. Based on these indicators, SJ Humanitas students favorably assess their learning opportunities, outcomes, and environment.

Community schools, like SJ Humanitas, are increasingly elevated as an equity-driven, research-based approach that can address students’ social, emotional, and academic needs. By definition, community schools represent a place-based approach in which “schools partner with community agencies and local government to provide an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, and community engagement.”Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Learning Policy Institute. At their foundation, community schools hold key values, including a deep commitment to students, families, and community stakeholders and an acknowledgment of their assets and power to enable and support equitable schooling. They also typically have characteristic school features—or pillars—that seek to holistically support student success and well-being (see “Community School Pillars”).

Community School Pillars

- Integrated student supports address out-of-school barriers to learning through partnerships with social and health service agencies and providers.

- Expanded and enriched learning time and opportunities, including in-school, after-school, weekend, and summer programs, provide additional academic instruction, individualized academic support, enrichment, and learning opportunities that emphasize real-world projects and community problem-solving.

- Active family and community engagement involves parents and other community members in the school as partners in shared decision-making around children’s education.

- Collaborative leadership and practices seek to build a culture of professional learning, collective trust, and shared responsibility.

Source: Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/community-schools-effective-school-improvement-report

Many policymakers and educators focus on the role that community schools play in providing external supports for students, rather than how they influence the character of teaching and learning to enable student success. This case study addresses this critical aspect of effective community schools, illustrating how SJ Humanitas implements a range of whole child education practices to advance student outcomes and well-being.

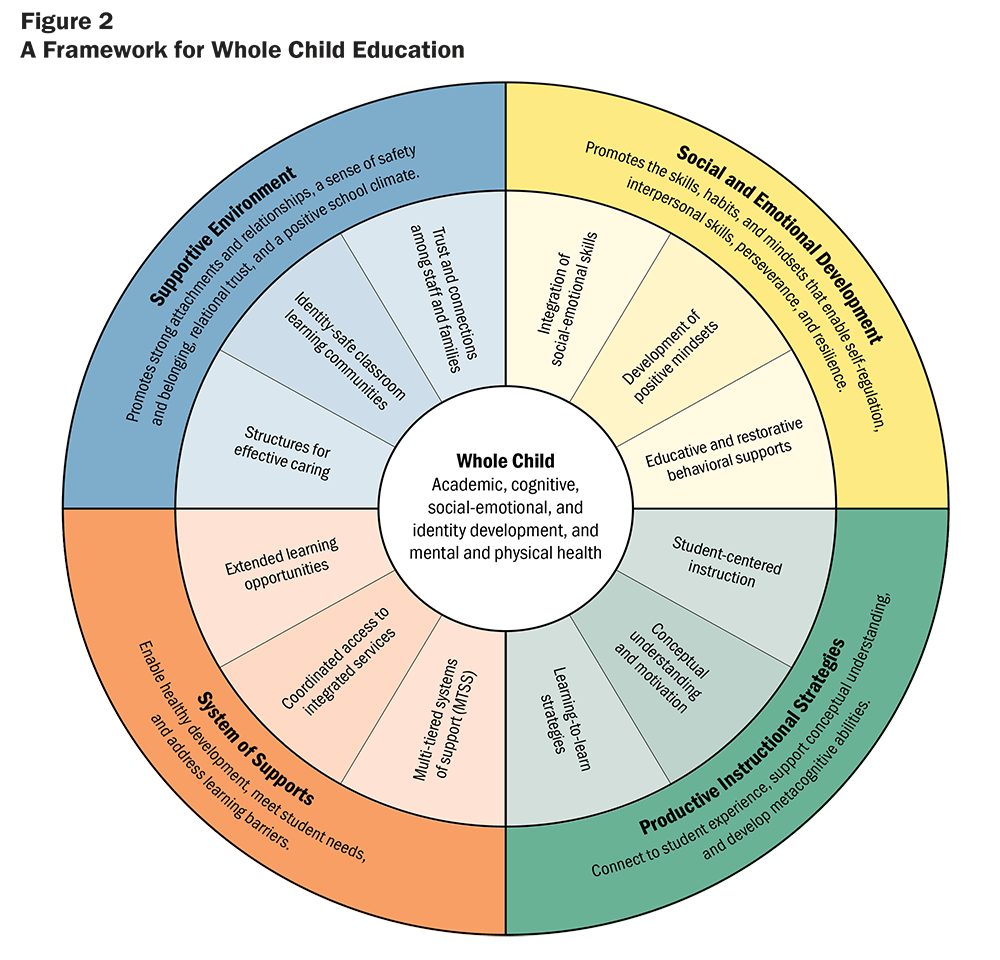

Holding all the key features of a community school, SJ Humanitas honors and nurtures whole child development in ways that are supported by the science of learning and development (SoLD) that has emerged from neuroscience, cognitive science, and the developmental sciences over the past several decades. A recent synthesis of that research points to the importance of four principles for educational practiceDarling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. (see Figure 2):

- Supportive environments that promote strong attachments and relationships; a sense of physical and psychological safety and belonging; and connections among educators, school staff, and families.

- Social and emotional development to promote the skills, habits, and mindsets that enable self-regulation, interpersonal skills, and resilience, along with behavioral supports that are educative and restorative.

- Productive instructional strategies that support motivation and engagement, build on children’s prior knowledge and experiences, and develop students’ ability to learn how to learn.

- Systems of supports that enable healthy development, meet student needs, and address learning barriers, including multi-tiered systems of support and expanded learning opportunities.

These four SoLD principles characterize the practices observed at SJ Humanitas, each of which are described in the sections that follow.

Whole Child Practices at SJ Humanitas

Fostering Relationships in a Supportive Environment

SJ Humanitas creates a supportive school environment that lays the foundation for learning and holistic development and works to ensure the school is a true community space. To achieve these aims, the school holds a deep commitment to relationships and has implemented structures and practices that enable staff to know students, families, and colleagues well.

SJ Humanitas is a small school, which enables staff to establish strong, personal connections. In addition, the school follows a block schedule, which provides extended time for relationship building among peers and between teachers and students and offers opportunities for more in-depth group work. Educators also hold weekly office hours before and after school, which allow students to reach teachers and receive additional support. The office hours supplement the school’s open-door policy that invites students to visit staff when they are struggling with difficult issues. Everyday routines, like teachers greeting students as they arrive to class, also provide opportunities for educators and youth to build connections that support learning and well-being. During student focus groups, students explained that this collection of practices makes them feel valued by school staff and reinforces that their teachers care about their growth and success in the future.

Advisories are also an important forum for relationship building. At SJ Humanitas, one teacher and a cohort of approximately 25 students regularly convene during advisory periods throughout the course of the year. According to the school’s Advisory Teacher Guide, advisories are intended to be “a period in the day during which our students are able to process, and reflect on what they are learning, and use that information to shape and inform their character, ethics, and sense of justice.” To do this, advisories meet four times a week and provide students opportunities for community building, social and emotional learning (SEL), and career- and college-readiness skill development. Advisories also provide time for students to receive academic support from their advisors and to collaborate with their peers to build their knowledge and skills. Teachers indicated that, because of the dedicated time and space for building connection, advisories help them understand what a student might be going through, in and out of school, and better serve as a student’s advocate—a key advisor role and responsibility. Advisors are able to respond more quickly and with more understanding when struggles emerge and to facilitate important communication with families and other staff to address student needs.

In addition to building connections between students and staff, SJ Humanitas fosters supportive relationships among its practitioners. Grade-level teams and structured collaboration time facilitate interdisciplinary lesson planning and the development of professional and caring relationships among staff, and teachers consistently report feeling supported by their colleagues and administrators and valuing this focus on adult relationships.

Like many community schools, SJ Humanitas seeks to create a supportive environment by meaningfully engaging families to support student learning and growth. To build connections with families, the school hosts multiple events geared toward parents and guardians, including parent advisory nights. These events are held each semester and provide a forum to discuss community challenges and to experience the same kinds of SEL practices that students engage in during the day. Other noteworthy family events are student-led conferences, in which students lead a discussion with their families and teachers to reflect on how they are doing and what they are learning in each class.

This family engagement is strengthened by the school’s collaborative structures, which allow SJ Humanitas’s practitioners, students, and families to build and share their expertise to inform how the school advances student progress and well-being. These structures include the Governing School Council—a feature of LAUSD’s Pilot Schools—and the Instructional Leadership Team, which both lay the foundation of SJ Humanitas’s approach to supporting student development and demonstrate its commitment to creating an inclusive school environment.

Taken together, these practices cultivate a supportive environment in which all individuals are valued and their expertise is meaningfully and democratically incorporated into decision-making. In doing so, they set the stage for engaging students in rich learning and development.

Developing Social and Emotional Capacity

Practitioners at SJ Humanitas understand that social and emotional development is central to learning and well-being and, in turn, have made SEL an area of focus at their community school. Social and emotional skills, mindsets, and habits are developed at SJ Humanitas in several overlapping ways and are reinforced by educators and community partners.

Teachers use a variety of tools to assess students’ social and emotional strengths and needs to provide more personalized supports. For example, the Developmental Assets Profile from the Search Institute helps educators identify students’ social and emotional competencies. Teachers also use a survey based on the book The Five Love Languages by Gary Chapman to tailor students’ and teachers’ expressions of care and appreciation to what makes each individual feel valued.

With data from these tools, SJ Humanitas educators implement a range of SEL experiences. For example, students receive explicit SEL instruction, which supports them in developing competencies related to emotional awareness, self-efficacy, leadership, and resourcefulness. Much of this work occurs in advisories. A noteworthy routine during advisory is council—a practice of many ancient and Indigenous cultures that engages participants in a listening circle to build community and make space for everyone’s voice. Council engages participants in building social and emotional skills, including emotional awareness, active and respectful listening, and empathy building, all while cultivating community and a safe and reflective space. One alumnus cited an old Aztec saying that he learned at SJ Humanitas that stayed with him: “You are my other me. If I do harm to you, I do harm to myself.” He asserted that SJ Humanitas “taught us how to be kind to other people, even if we may not agree with their opinions.”

In addition, educators at SJ Humanitas integrate opportunities to develop students’ social and emotional capacity during content-related instruction, in which teachers reinforce and intentionally model these skills in their teaching—a practice that can positively influence the learning climate and offer examples of how to navigate stress or build healthy relationships, among other skills.CASEL. (2019). The CASEL Guide to Schoolwide SEL. For example, SJ Humanitas teachers often use check-ins to guide students in exploring their social and emotional states before delving into academic learning, which can help the students develop emotional literacy as they take the time to notice, accurately name, and interpret their emotions in a learning setting.Martínez Pérez, L. (2021). Teaching With the HEART in Mind: A Complete Educator’s Guide to Social Emotional Learning. Brisca Publishing.

Opportunities for SEL are also integrated into academic instruction. Teacher Jael Reboh provided a strong illustration of this in his English classroom. Reboh engaged his sophomores in a high-level analysis of the book Night by Elie Wiesel. In the book, Wiesel describes his experience as a teenager, living with his father in two Nazi concentration camps. Using Night as a testimony of human suffering and resilience, Reboh creates the opportunity for students to reflect on their own strategies to cope with challenges and have meaningful conversations about hate, compassion, and survival.

Restorative approaches at SJ Humanitas are also instrumental in supporting students’ social and emotional growth.Klevan, S. (2021). Building a positive school climate through restorative practices. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/178.861 The school’s restorative approach to behavior management is rooted in the following principles:

- building and sustaining community

- restoring the harm, not punishing the person

- upholding students’ and teachers’ humanity

- building character and resourcefulness

Guided by these principles, SJ Humanitas uses restorative practices to teach students skills that enable positive behaviors, encourage them to take responsibility for their actions, and help them make amends to restore relationships when needed. In practice, this has included the use of restorative circles when school rules are broken, which gives students and teachers the opportunity to articulate how the students’ behaviors affected them. In addition, teachers described how a restorative approach prompted them to more intentionally ask students the reasons behind their behaviors (e.g., missed assignment, late to class) instead of applying consequences without knowing the causes. Overall, SJ Humanitas’s embrace of restorative practices has helped nurture a culture of open dialogue among educators and students, enable students to practice self-expression, and proactively build the skills they need when conflicts arise.

Learning how to make one’s voice heard to resolve disputes and improve the community is a desired outcome at the school. For this reason, SJ Humanitas creates opportunities for students to find their inner leader through a mentor program, which trains select students to serve as mentors to other students. The Student Steering Committee is another structure for leadership development, which enables students to voice their opinions and take an active part in shaping the quality of their education. These student leadership opportunities support students in building important social and emotional skills that they will need to be successful in college and beyond.

Furthermore, fostering social and emotional development and well-being is not restricted to students. SJ Humanitas understands the importance of helping teachers develop the social and emotional skills they need to teach SEL, implement restorative practices, and take care of their own needs. Practitioners indicated that attention to adult wellness was an important aspect of SJ Humanitas’s commitment to all community members’ self-actualization and to establishing a learning environment in which adults are active participants. The school uses professional development opportunities, like staff retreats and meetings, not only as learning spaces but also as a time for faculty to come together as a group and take the pulse of how everybody is doing. Targeted professional development also focuses on social and emotional skills and on providing teachers with the tools to engage in and lead this work. With these learning forums, the school hopes to create an environment that enables adults and students alike to take risks, make mistakes, acknowledge areas for improvement, and try again. The important thing, according to Principal Jeff Austin, is to let teachers know that SJ Humanitas is an environment in which teachers can share their mistakes and struggles and receive the supports they need to keep improving.

Implementing Rich, Culturally Relevant Instruction

To drive learning, educators at SJ Humanitas use rich, culturally relevant pedagogical approaches that are guided by the school’s principles of social justice and self-actualization. The school’s shared instructional practices include the use of interdisciplinary units, shared inquiry with a critical lens, culturally relevant content for identity exploration, scaffolding, and opportunities for individualized learning and growth. The science of learning and development tells us that instructional strategies like these fuel student learning. The research explains that skillfully implemented instruction that incorporates experiential and culturally affirming instruction, conceptual understanding and motivation, and adequate supports for learning are powerful practices that enable academic and cognitive growth.Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. SJ Humanitas has implemented these instructional approaches as a means of supporting students in reaching their fullest potential.

The school’s use of interdisciplinary units of study and assessments allows students to make connections across content areas, particularly as they explore issues related to equity, justice, and their local communities. To illustrate, after learning about various social movements in humanities and art classes, 10th-graders work in small groups and use the newly learned concepts and skills in a culminating project that entails writing an essay or creating a play to demonstrate their learning around one movement. These interdisciplinary projects exemplify an effective way to incorporate a variety of whole child instructional practices—collaborative and interest-driven learning tasks connected to students’ life experiences and performance assessments—while providing an enriched learning opportunity for students.

Student learning in history and humanities classes also exemplifies how educators at SJ Humanitas engage students in shared inquiry—which emphasizes inferential reasoning, questioning, and student-to-student talkDarling-Hammond, L., Barron, B., Pearson, P. D., Schoenfeld, A. H., Stage, E. K., Zimmerman, T. D., Cervetti, G. N., & Tilson, J. L. (2015). Powerful Learning: What We Know About Teaching for Understanding. John Wiley & Sons.—about complex topics with a critical lens. Students are asked to research evidence that represents a wide variety of perspectives and work in small groups to analyze rhetoric, historical events, or media literacy from multiple points of view. Teachers use document-based questions, which are included in the Advanced Placement (AP) history exams, to guide many of the lessons they teach. In addition, teachers use experiential activities such as mock trials, debates, Socratic seminars, or role-playing to actively engage students and develop their capacity to analyze events with a critical lens.

Educators at SJ Humanitas also use culturally relevant pedagogical practices to provide students with opportunities to develop their sense of confidence as individuals and increase their engagement in learning. For instance, SJ Humanitas practitioners utilize media and literature pieces that are relevant to students’ lives and experiences to allow for personal connections while developing literary and analytic skills. In addition, educators explore culturally relevant topics across content areas to integrate identity-affirming practices in all aspects of student learning. To illustrate, in an AP English class, the teacher started one class with the guiding question, “What does it mean to be African American in America?” An African American student shared that as she started reading and learning about U.S. history, she realized there were many things she did not know about her ancestors. Culturally relevant learning opportunities are also infused into the school’s interdisciplinary curriculum as educators ask students to analyze their intersectional identities and personal histories—including their traumas—and how these affect their lived experiences.

In using culturally relevant practices like these, educators at SJ Humanitas explained, they want students to develop their voice and “unlearn” many of the negative beliefs they carry about themselves and their communities, learned over the years. As teacher Eugenia Plascencia explained, the community school’s use of culturally responsive practices aims to further students’ belief that they will succeed and achieve the best versions of themselves because of who they are and the experiences they have had, not despite them. Current and former students also saw SJ Humanitas as an identity-affirming place that informed how they navigated the spaces beyond school walls.

SoLD indicates that students learn and communicate in different ways and at different paces, which requires teachers to individualize learning to support students on their personal trajectories.Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. At SJ Humanitas, teachers use scaffolding tools and strategies to ensure that lessons are engaging and challenging and that all students can access the content taught in class. They use a combination of individual work, group discussion, and pair sharing to support students’ understanding and acquisition of complex topics and skills. In addition, educators draw on a range of assessment strategies, such as quizzes, student conferences, classroom observations, interdisciplinary project rubrics, performance assessments, and student self-assessments, which help them gain insights to better personalize instruction and support students’ growth.

Educators balance individualized attention to students with opportunities for students to work at their own pace. At SJ Humanitas, teachers recognize and value mistakes as part of learning. When students may have not acquired a skill or understood a concept the first time around, teachers provide several opportunities for them to gain that knowledge and make up missing assignments or failed assessments in class or during office hours. Approaches like these not only recognize students’ individual paths to learning, but also give students the chance to receive regular feedback, which helps them develop confidence and competence as they see improvements in their work as a result of their efforts.Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140.

Teachers learn the school’s shared pedagogical practices through a robust agenda for professional development that leverages staff expertise and exemplifies the value the school places on teacher leadership. Principal Austin says he looks to the community for ideas and sees himself as the “collector” of these ideas, with a responsibility to “find the collection of expertise within the staff.” In turn, professional learning opportunities, ranging from the annual staff retreat to weekly grade-level team meetings, serve as important spaces for teachers to collaborate and develop their interdisciplinary projects and to share their knowledge of students to identify appropriate supports to advance learning.

Instituting a System of Supports

SJ Humanitas aligns school and community resources to provide a system of supports for its school community as part of its whole child approach. This system aims to boost academic progress and well-being by providing relevant services, opportunities, and interventions that are responsive to individual learners’ needs.

Notably, this system includes the school’s multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). With the centrality of relationships at this community school, SJ Humanitas sees relationships as a key strategy for identifying the need for academic, social, and emotional supports. Thus, its MTSS leverages its relationship-building structures and everyday practices (e.g., advisory, council, mentoring, restorative practices, office hours, small group instruction) as universal supports, which enable all students to feel known while helping staff discover their unique strengths and needs. Supplemental and intensive supports, such as the school’s practice of “adoption,” are provided when universal supports are not sufficient to meet a student’s unique needs. In this practice, each teacher assumes a caseload of three to four students who need additional support and may benefit from a deep one-on-one relationship with an adult.

All students at SJ Humanitas also benefit from access to on-site and off-site care and support when needed, including the school’s academic counseling staff. In 2018–19, there were three dedicated academic counselors for the campus of 521 students, which is a lower caseload than the average 433 students per counselor in LAUSD. The school’s budget flexibility—an autonomy afforded by its pilot school status—enables the school to invest in academic counselors and establish a counselor caseload that fosters relationship building and ongoing support for students’ holistic needs. In addition, the school has a school-based psychiatric social worker who provides intensive services for students with acute mental health needs and maintains a full-inclusion model for students with special needs.

To increase the power of its MTSS, SJ Humanitas also provides expanded and enriched learning opportunities that take place after school or beyond the school campus. Often offered in partnership with community organizations, these learning experiences provide students with the opportunity to learn from additional adults who support students and enable them to develop trusting relationships that foster learning, development, and student well-being. For example, students can participate in a range of “interest clubs,” such as guitar, fitness, and American Sign Language through the after-school program, or enroll in teacher-sponsored clubs, such as Pride Club, Teens United, and Academic Decathlon, among others. In addition, organizations such as Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural and Bookstore, the Skirball Cultural Center, and the University of California, Los Angeles’s (UCLA’s) UniCamp offer off-site learning opportunities for students to lift their voices and explore their community and surrounding areas.

A system of integrated services, including services that address academic, social and emotional, health, mental health, and safety needs, is also in place at SJ Humanitas. While school staff noted some challenges in systematically tracking and accessing these integrated services, teachers and administrators indicated that partnerships play a key role in extending the school’s capacity. Partnerships with community organizations and external service providers are fundamental to sustaining SJ Humanitas’s approach to community schooling and, according to Principal Austin, help the school achieve its goal of being a resource “where you can find out where to get help” for students and families.

For example, the school maintains a partnership with Mission City Community Network, a mobile health clinic that offers a range of physical and mental health services on a weekly basis, and with Hathaway-Sycamores Child and Family Services, which provides crisis intervention and individual, group, and family therapy. SJ Humanitas also leverages a noteworthy partnership with EduCare Foundation—a nonprofit established in 1990—which assists in organizing the delivery of services, such as physical and mental health services and college access support, and oversees an initiative focused on SEL. EduCare’s relationship with the school has deepened over time, and the school has a dedicated full-time EduCare site coordinator who works directly with students on professional development and connects the school with additional partners, with the ultimate goal of addressing students’ holistic needs.

These efforts to secure and provide a range of integrated services at SJ Humanitas are intended to help students feel empowered as individuals with unique needs and to normalize the practice of soliciting supports. One student shared how these supports have made a lifelong difference: “It really stuck with me, knowing that I can seek out help and that I’m not going to be shamed.”

Additional community partnerships have expanded into the realm of professional learning. For example, partnerships with UCLA’s Center X and California State University, Dominguez Hills enable practitioners to connect with a network of teachers and professors to better understand and implement whole child education practices.

Reinforcing Whole Child Education in Community Schools

As this case study shows, SJ Humanitas is committed to whole child education. The school implements an array of practices and structures that allows this commitment to come to life, which has, in turn, had a measurable impact on students and their outcomes. Yet the school’s ability to create a rich and supportive learning environment that enables student success was nurtured not only by its commitment to whole child education principles, but also by its characteristic community school pillars that attend to students’ academic, social, and emotional development in student-centered and culturally relevant ways (see “Community School Pillars”).

Together, these features coalesced to build a learning environment that supported students’ development and success and demonstrated the school’s commitment to relationship building, collective responsibility, and democratic principles.

Educators and administrators at SJ Humanitas point to the school’s identity as a community school as a key reason why they have been able to implement and sustain this approach. At SJ Humanitas, whole child practices provide support for and are supported by its community school approach and underlie the school’s ability to provide a high level of care to students and ensure their growth and development.

This in-depth investigation into SJ Humanitas demonstrates that community school pillars and SoLD-aligned principles can be mutually reinforcing as they work together to build learning environments that support whole child development and academic success. This finding suggests that instead of being focused on the provision of external supports, community schools may be institutions that are uniquely positioned to implement whole child education practices that propel learning and well-being.

Social Justice Humanitas: A Community School Approach to Whole Child Education (research brief) by Lorea Martinez, Laura E. Hernández, Marisa Saunders, and Lisa Flook, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Photo used with permission by Social Justice Humanitas Academy.