Closing the Opportunity Gap: How Positive Outlier Districts in California Are Pursuing Equitable Access to Deeper Learning

Summary

One of the mysteries of education reform is how leaders and educators can successfully instantiate, sustain, and spread student-centered pedagogical practices from a few schools to many others. Advocates for deeper learning grapple with this mystery as they seek to transform teaching and learning to prepare students to meet the demands of the 21st century and to close the opportunity gap between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. While research suggests that deeper learning strategies that support critical thinking and problem-solving can yield improved student outcomes, implementing these strategies is not easy, as they require reimagining school environments and changing traditional approaches to teaching. This brief highlights how three networks of schools engaged in deeper learning have managed this feat. It describes the systems and structures the networks have used to instantiate their equitable deeper learning models in diverse public school settings to serve students in more personalized and productive ways.

The full report can be found online here.

District Case Studies

Closing the Opportunity Gap: How Positive Outlier Districts in California Are Pursuing Equitable Access to Deeper Learning is a cross-case analysis of seven individual case studies of school districts. Those case studies are available below.

Chula Vista Elementary School District

Laura E. Hernández and Crystal A. Moore

Clovis Unified School District

Joan E. Talbert and Dion Burns

Gridley Unified School District

Dion Burns and Patrick M. Shields

Hawthorne School District

Taylor N. Allbright, Julie A. Marsh, Eupha Jeanne Daramola, and Kate E. Kennedy

Long Beach Unified School District

Desiree Carver-Thomas and Anne Podolsky

Sanger Unified School District

Joan E. Talbert and Jane L. David

San Diego Unified School District

Laura E. Hernández and Anne Podolsky

To succeed in a fast-changing society with rapid growth in knowledge and new technologies, there is a growing consensus among researchers and educators that all young people need critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and communication competencies—often referred to as “deeper learning” skills. Once reserved for a small minority of students, opportunities to develop these skills are necessary for all students to survive and thrive in a 21st-century society characterized by complexity and continuous change.

Unfortunately, disparities in students’ learning opportunities present a persistent problem: These inequities result from growing income inequality over the past 3 decades and the failure of many states to invest equitably in schools that serve a diverse student population. Providing equitable access to deeper learning opportunities is perhaps the major challenge of 21st-century education in the United States.

Fortunately, many schools and districts are rising to this challenge. The report on which this brief is based examines a set of seven “positive outlier” districts in California in which students are consistently outperforming students of similar racial/ethnic backgrounds from families of similar income and education levels in most other California districts. In addition, these districts are achieving more equitable opportunities and outcomes across a range of measures. This brief consolidates lessons from seven of these successful districts initially identified through a quantitative analysis of district performance across the state and chosen because of their geographic and demographic diversity. Our analysis of the individual cases revealed several commonalities in the key strategies and principles pursued across the districts:

- a widely shared, well-enacted vision that prioritizes learning for every child;

- instructionally engaged leaders;

- strategies for hiring and retaining a strong, stable educator workforce;

- collaborative professional learning that builds collective instructional capacity;

- a deliberate, developmental approach to instructional change;

- curriculum, instruction, and assessment focused on deeper learning for students and adults;

- use of evidence to inform teaching and learning in a process of continuous improvement;

- systemic supports for students’ academic, social, and emotional needs; and

- engagement of families and communities.

This brief begins by describing California’s context and the district role in supporting student learning, followed by a snapshot of the seven positive outlier districts and a summary of lessons learned. It concludes with recommendations for federal and state policymakers and district administrators.

The California Context

To focus schools on 21st-century learning goals, California’s State Board of Education adopted the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in English language arts and mathematics in 2010 and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) shortly thereafter. These standards focus on the analytic and inquiry skills that undergird deeper learning, as does the new assessment system that accompanies these standards, the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP), adopted from the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium. CAASPP includes performance items and tasks designed to reflect a greater depth of knowledge and more thoughtful application of skills.

Meanwhile, in a major departure from years of budget cuts, the state passed Proposition 30, which increased funds for education, and adopted a much more equitable approach to school funding—the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Enacted in 2012, LCFF equalized funding, eliminated categorical programs, and provided additional resources to support education for students from low-income families, English learners, and those in foster care. This funding reform was paired with a new accountability system, the Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP), which requires school districts to evaluate annually the progress of student groups on multiple indicators of student opportunity and learning, to seek input from parents and community members about how to allocate resources for learning, and to lay out how LCFF funds will be used to support student learning.

In combination, these initiatives represent a sea change in California’s education policy and in the opportunities and expectations for change within local school districts. With the support of LCFF, LCAP, and the broadening evidence base about district effectiveness, California districts had a unique opportunity to respond effectively, and some have done better than expected in providing deeper learning opportunities to all students. Policymakers and educators have a unique opportunity to learn from these districts.

The District Role in Educational Improvement

Although much research, along with recent federal policy, has focused on evaluating and improving individual schools,U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2006). LEA and school improvement: Non-regulatory guidance (Rev. ed.). Washington, DC: Author; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2011). Guidance on fiscal year 2010 School Improvement Grants under section 1003(g) of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. Washington, DC: Author. more recent research has shown that districts are critically placed to make a difference in school practices and outcomes.Sykes, G., O’Day, J., & Ford, T. (2009). “The District Role in Instructional Improvement” in Sykes, G., Schneider, B., Plank, D., & Ford, T. G. (Eds.) Handbook of Education Policy Research (pp. 767–784). New York, NY: Routledge; Zavadsky, H. (2013). Scaling turnaround: A district-improvement approach. American Enterprise Institute, 70(1), 16; Dunn, L., Scott, C., Chapman, K., & Vince, S. (2016). The missing link: How states work with districts to support school turnaround. San Francisco, CA: WestEd. Districts routinely allocate resources to schools; organize key functions such as the hiring, assignment, and support of personnel; and often influence what is taught, how it is taught, and how it is assessed. Districts can create policies regarding school design, instructional strategies, student discipline, and family engagement, and they often direct the work of educators in their implementation. In all this work, districts must interpret federal and state policy as they attempt to create many of the conditions for teaching and learning. Moreover, districts offer the potential for scaling up change from schools to systems in a sustainable way, rather than engaging in isolated efforts that transform educational practice one school at a time.

Over the past several decades, much has been learned about the role districts play in influencing student learning outcomes. A summary of 31 studies of district effectiveness found 10 district characteristics, or practices, associated with high performance: a districtwide focus and vision for student achievement, clearly established and aligned curriculum and instruction, use of evidence for decision-making, a districtwide sense of efficacy, building and maintaining good communications and relationships, investing in instructional leadership, a targeted and phased orientation to school improvement, job-embedded professional learning for leaders and teachers, strategic engagement with the government’s agenda for change and associated resources, and infrastructure alignment.Leithwood, K. (2010). Characteristics of school districts that are exceptionally effective in closing the achievement gap. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 245–291. Further, some research suggests that what separates successful districts from others is their ability to take a systemic approach, with a comprehensive strategy employing many of the elements described above.Zavadsky, H. (2013). Scaling turnaround: A district-improvement approach. American Enterprise Institute, 70(1), 16; Zavadsky, H. (2016). Bringing effective instructional practice to scale in American schools: Lessons from the Long Beach Unified School District. Journal of Educational Change, 17(4), 505–527. Our research examines these elements to add to the growing body of lessons for educators and policymakers.

Snapshot of Positive Outlier Case Study Districts

This section highlights each district’s context, its strategic priorities, and the factors that contributed to its success. Then we summarize the performance of these districts.

Positive Outliers’ Contexts and Approaches

Chula Vista Elementary School District is located just south of the city of San Diego, about 7 miles north of the U.S.–Mexico border. The district consists of 47 schools, which include five dependent and two independent charter schools. Chula Vista is the largest elementary school district in the state, with 1,500 teachers and 30,000 students in kindergarten through 6th grade. Chula Vista’s approach to continuous improvement was based on a philosophy known locally as “interdependence,” which clarified and balanced the respective roles of district and schools. The district also supported professional learning cycles for school-site educators and district leaders in which training was followed by opportunities to practice, receive feedback, and observe colleagues, thus supporting iterative improvement. Chula Vista took a slow, deliberate approach to the CCSS, building knowledge and awareness of the standards prior to full implementation. The district used data to inform its efforts to address student needs, particularly those of English learners, and to support student learning with a districtwide instructional vision and skill-specific teacher coaching.

Clovis Unified School District is a midsize district located in Fresno County in California’s Central Valley. Clovis fosters area- and site-level innovation, encouraging leaders to compete with one another’s schools and learn from each other’s successes. Its multistep hiring process for teachers takes into account academic factors, personal disposition, and suitability to teaching. Taking its own approach to the new standards—the “Clovis Way”—the district developed CCSS-aligned curriculum guides and interim assessments, for which it received a 2016 California School Boards Association Golden Bell Award. Decision-making in the district is shaped through the collection and analysis of a range of data at each level of the system, and the district has established a variety of support services, including “transition teams” when students change schools and targeted counseling services for historically underserved students.

Gridley Unified School District is in a small town of around 6,500 in Butte County, located in the upper Sacramento Valley. Due to its size, Gridley operates with few district office staff and thus encourages site-level leadership and strong community relationships. Gridley has been able to maintain a stable core of teaching staff and to avoid significant layoffs and other financial challenges during the Great Recession. A strong emphasis on early literacy and tiered interventions for literacy in elementary and middle school has supported the strong performance of students.

Hawthorne School District is a small district in a working-class suburb of the Los Angeles metropolitan area’s South Bay region. Hawthorne has received notable attention for high performance, with five of the district’s seven elementary schools earning Gold Ribbon status from the state of California in 2016. District educators attribute this success to developing a climate of trust and strong relationships among educators through stable and collaborative leadership, a clear vision for staffing, and centralized coaching and support for instruction. The district took a deliberate approach to adopting the CCSS, building capacity and buy-in among teachers. Hawthorne provides targeted support for its English learners and is increasing its emphasis on students’ social and emotional learning. Hawthorne has reduced suspensions and expulsions through its support for positive behavior practices and associated professional learning for teachers regarding culturally responsive teaching and learning.

Long Beach Unified School District is the third largest district in the state and has won several awards for its improvement processes and success with students. The district has worked closely with California State University at Long Beach and Long Beach City College on student articulation from pre-kindergarten through college. Known as the “Long Beach College Promise,” the partnership has helped students better prepare to meet the demands of postsecondary studies. Close partnerships with CSU-Long Beach for preparing teachers and leaders have also supported a coherent vision and strong instruction in the district. Long Beach has focused on aligning expectations and supporting schools to promote improved instruction and remove barriers to advanced coursework, while also working to support students’ social and emotional learning. The district’s strategic approach to improvement has centered on a standards-aligned instructional vision supported by investments in collaborative professional learning at multiple levels, which build educators’ collective efficacy.

San Diego Unified School District is the second largest district in California. Key elements of the district’s strategy include a clear instructional vision, investments in coaching to support teaching, and professional learning cycles that engage teachers in ongoing analysis of data and teaching practice to improve student outcomes. The district has developed a multidimensional equity strategy to remedy opportunity gaps. The strategy emphasized literacy instruction, collaboration among educators to improve school climate, and multi-tiered systems of support for students. As part of this strategy, SDUSD took significant steps to broaden access to advanced coursework, implement restorative justice practices, and improve staff’s abilities to support students in their academic, social, and emotional development.

Sanger Unified School District is located a few miles southeast of Fresno. During the accountability era of No Child Left Behind, Sanger earned the reputation of being a successful “turnaround district” based on its students’ steep and steady improvement, especially for English learners and students with disabilities. Between 2004 and 2012, Sanger USD moved from being one of the lowest-performing California districts, under threat of state takeover, to exceeding statewide district averages on the California’s Academic Performance Index. By 2012, most of Sanger’s 20 schools had high student achievement compared to demographically similar schools, and many had received Blue Ribbon awards from the state.

Sanger’s success was aided by long-term investments in a stable, well-prepared teaching force; a culture of collaboration among and support for teachers; a proactive leadership pipeline; professional learning communities at all levels for continuous improvement; and shared accountability within schools and between each school and the district. The district’s priorities for change in moving to the new standards included renewing training for effective professional learning communities, establishing processes for effective instruction, and building multi-tiered systems of support for students.

Performance of Positive Outlier Districts

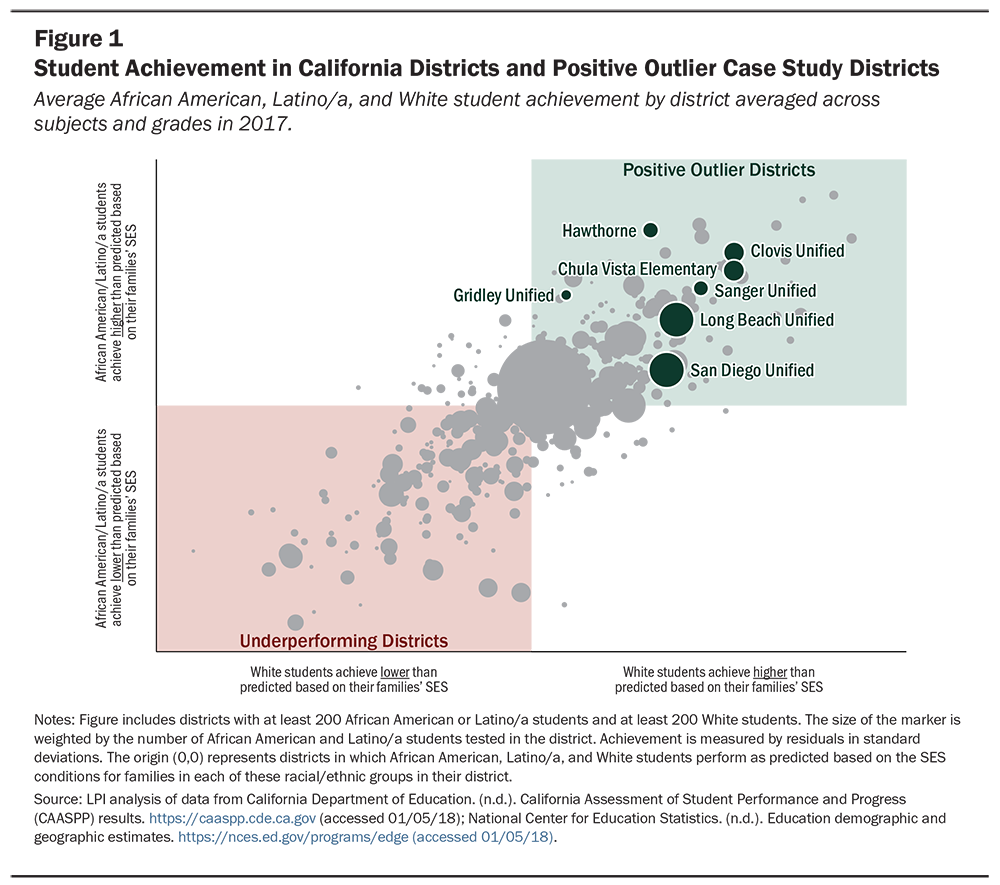

Figure 1 shows the variation in student achievement across the 435 California districts that have at least 200 African American or Latino/a students and 200 White students (i.e., those large enough to have reliable estimates).The measures of district performance used in this study are the residual scores produced by a statistical model that assessed the difference between districts’ predicted CAASPP ELA and math scores and their actual average scores in 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17 for African American, Latino/a, and White students.

Districts in the top right quadrant of Figure 1 are identified as positive outlier districts because African American and Latino/a students, as well as White students, achieve at higher-than-predicted levels, controlling for their socioeconomic status. In contrast, districts in the lower left quadrant are identified as underperforming because students of these racial/ethnic groups achieve at lower-than-predicted levels, controlling for their socioeconomic status.

In addition to strong academic performance in ELA and math from 2015 through 2017, positive outlier districts also had strong graduation rates among student groups. Four-year cohort graduation rates for Latino/a students in 2017 ranged from 80% in Gridley to 92% in Clovis, with all districts at or above the state average for Latino/a students of 80%. African American 4-year graduation rates in 2017 were also well above the state average in the four districts with a sufficient number of such students to provide data, ranging from 84% in San Diego to 100% in Sanger. The state average graduation rate for African American students was 73%.

Factors Examined

We used a case study approach to investigate the factors supporting higher-than-predicted outcomes for students of color and White students in the seven positive outlier case study districts. Factors examined included human capital issues, resources, instruction, curriculum, professional learning, social and emotional learning, data and accountability, culture, parents and community, schedules, and organization.

Data sources included documents—such as Local Control Accountability Plans, school schedules, program descriptions, and documents from after-school programs and professional learning communities—and 2-day site visits in fall 2017 and winter 2017–18, during which researchers conducted 30- to 60-minute interviews with a total of 226 district- and school-level staff across the seven case study districts.

To draw out lessons across the seven individual case studies, researchers reviewed each individual case study to identify common themes. These themes emerged from our review of the research evidence on exemplary districts, as well as the district context described in the individual case studies. This analysis allowed us to identify common elements that contributed to district success in implementing new standards that require students to demonstrate in-depth learning.

Lessons Learned

Although the seven positive outlier districts we studied do not hold all the answers to improving schools, our cross-case analysis offers some lessons that district and school leaders may consider as they work to provide meaningful learning for all students.

Prioritize learning for every child: In positive outlier districts, leaders set a clear vision for teaching and learning, which they communicated throughout the district. Equity was a central part of this vision and served as a touchstone for student-centered decision-making. Although the district vision was universal—applying to all schools, staff, and students—leaders struck a balance between a clear vision from the center and delegating considerable responsibility to school sites for how to enact that vision.

Build relationships and empower staff: District leaders supported instruction and intentionally built trusting relationships with teachers. Teamwork and collaboration were elevated as shared values and were central to the way districts approached continuous improvement.

Value and support stability and continuity: Leadership, teachers, and other staff at the district and school levels tended to be stable in positive outlier districts, with low rates of turnover. This stability contributed to the clarity of messages received from districts and communicated through structures such as instructional leadership teams and to the long-term coherence of programs. It also allowed districts to build on their successes, fine-tune their efforts over time, and build strong capacity.

Attract, develop, and retain well-prepared teachers and leaders: Although many are high-poverty districts, the positive outliers generally avoided the worst of California’s severe teacher shortages and hired relatively few underprepared teachers. These districts proactively created strong pipelines for educator hiring, often through partnerships with universities and Grow-Your-Own programs. They also worked hard to develop and retain teachers. They were regarded as attractive places to work, largely due to positive working environments and support for teaching. They further developed talent within the district, creating a pipeline with outreach to and training for potential leaders, from teacher to principal to district administrator.

Build collective efficacy through shared instructional learning: Positive outlier districts use collaborative professional learning as a key to improvement, building upon existing structures, such as professional learning communities, to support teacher and administrator learning and problem-solving. Professional learning in several districts took place at both the district and school levels. Leaders were instructionally engaged through cross-role collaborations that facilitated the sharing of successful practices across schools, thus allowing successful practices to move throughout the district. Positive outliers also made investments in teacher coaching, often accompanied by professional learning cycles. These inquiries typically centered on analyzing student learning, using data to inform instruction, and building teacher capacity to drive improvement. Districts also established strategic partnerships with external professional development organizations, sustained over time to introduce and develop specific skills.

Take a developmental approach to instructional change: Positive outlier districts took a phased approach to the implementation of the new standards, focusing first on providing time for teachers to unpack the standards and understand their expectations, then engaging in professional learning to support instructional shifts. By building teacher capacity for instruction and engaging teachers in selecting and creating curriculum plans, materials, and assessments, districts helped teachers develop a deeper understanding of the standards and buy-in for the change to these standards. Positive outlier districts identified challenges in standards implementation. They listened to and learned from teachers’ experiences and adjusted their approach where needed. This approach ensured that the standards and curriculum would take center stage, and that instruction would be teacher-led and student-centered, not textbook-driven.

Support collaborative, inquiry-based instruction and assessment focused on deepening understanding: Positive outlier districts supported teachers as they made standards-aligned instructional shifts that provided students with greater opportunities to engage in inquiry and collaborative learning in order to make meaning of their learning. The districts also increased the use of formative assessment to gauge student progress and inform instruction. This approach favored mastery of standards rather than coverage of curriculum.

Use data and evidence strategically to inform teaching and learning: Positive outlier districts used data and evidence to improve practice, not to punish teachers or students. Educators used multiple sources of data and evidence—about student needs, behaviors, and outcomes across social, emotional, and academic domains, as well as school and teacher practices—to inform teaching and learning, identify students in need of supports, and evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions. Data and evidence influenced decision-making at multiple levels, from district offices to instructional leadership teams, in professional learning communities, and as part of coaching cycles. Several districts made investments in data systems and professional learning on data analysis to boost teacher and school leader capacity to analyze and interpret data.

Activate instructional supports for students based on their needs: All positive outlier districts used data to identify students for additional supports and targeted interventions, such as Reading Recovery and English Language Development instruction, to support their success. Additional supports for student learning, including for students with disabilities and English learners, were increasingly framed in terms of multi-tiered systems of support and encompassed both academic and social and emotional learning. Positive outlier districts also worked to develop strategies such as culturally responsive teaching and learning, trauma-informed teaching, restorative justice practices, and family engagement to support student learning in and beyond school.

Policy Recommendations

Policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels can support the kinds of strategies and practices enacted by positive outlier districts that contribute to supporting student learning. From these lessons, at least five areas for policy work emerge:

1. Develop a stable supply of well-prepared, instructionally engaged teachers and leaders.

The positive outlier districts focused on staffing and built pipelines and systems to recruit and—importantly—keep good teachers and leaders. They sought and helped train strong candidates to hire, often in partnership with nearby schools of education; ensured supportive mentoring; and invested in ongoing professional learning. They identified and developed leadership talent among teachers to enable them to mentor, coach, lead school improvement, and, in some cases, move into principalships and central office positions. They treated educators as a valuable resource—not as interchangeable widgets—hiring carefully and supporting them once hired. District leaders joined teachers in focusing on instruction as schools worked to implement rigorous and meaningful learning opportunities for all students.

To ensure that all districts are able to build a similarly strong and stable educator workforce, state and federal policymakers have a responsibility to produce an adequate supply of well-prepared teachers and leaders. These policymakers can help expand high-retention pathways into teaching that research shows can both recruit and retain teachers. Building on service scholarships and forgivable loans that lower the cost barrier to entering teaching, such pathways include teacher and school leader residencies and Grow-Your-Own programs that recruit and prepare diverse candidates from the community who are committed to serve there. Given growing teacher shortages in certain high-need fields (special education, math, science, and bilingual education) and locations, incentives focused on these needs are particularly critical.

Districts then have the responsibility of careful selection, mentoring, and ongoing support. Districts should take a systemic approach to building a teacher and leader pipeline that is responsive to local needs. Making it a priority to hire and mentor well-prepared teachers who have the disposition and commitment to teach every child can reduce the risk of high teacher turnover and attrition, which is detrimental to student learning. Districts can also invest in the development of strong school leaders, who play an essential role in creating supportive working conditions and retaining teachers. Districts can provide opportunities for teachers to develop leadership skills, with opportunities to take on leadership roles as their skills and experience develop. Districts can also involve district and school administrators in ongoing professional learning and can create structures for collaborative learning and planning between teachers and administrators.

2. Support capacity-building for high-quality instruction and focused instructional change.

The positive outlier districts made sustained investments in implementing the new student learning standards as well as in instructional strategies designed to further deeper learning. These districts developed capacity for focused instructional change by engaging administrators in cross-role collaborations, investing in teacher collaboration through professional learning communities, and using professional learning cycles to implement new instructional strategies.

California’s overall approach to implementation of the new standards and a new state accountability system created an environment in which the positive outlier districts could undertake a careful, holistic approach. California introduced the CCSS and the Smarter Balanced assessments while also providing resources that could be used to build capacity, avoiding a rushed, top-down punitive approach that created backlash in some other states. The state is now in the process of developing a broader system of support, which should include access for all districts and schools to pedagogical expertise in each of the major disciplines as well as in meeting the needs of diverse learners who have historically been least well served by California schools, including English learners, students with disabilities, children who are homeless or in foster care, and African American and Latino/a students.

States can support teaching by selecting and developing high-quality assessments and using them for information and improvement, not for sanctions or punishment. They can allocate funds for professional learning and focus educators’ attention on a whole-child approach to education through accountability systems that take into account student outcomes across a wide variety of measures. These measures can include both status and growth on achievement measures and graduation rates, as well as indicators of opportunities to learn, such as suspension rates, school climate, and college- and career-readiness indicators.

Federal and state policies can invest in a strong, readily available infrastructure of high-quality professional learning opportunities that build the collective capacity of schools and districts to teach for 21st-century standards and to meet the full range of students’ academic, social, and emotional needs.

Districts can support capacity by focusing not only on outcomes but on the learning of educators to help all children meet those outcomes. These include professional learning communities and coaching cycles to implement new instructional strategies and develop them in practice, supported by observation and feedback. Districts can reach out to experts in areas that are the focus for improvement, as well as harness expertise among existing staff and invest in district teachers and leaders to support professional learning within the district.

3. Use assessments and data strategically to support continuous improvement.

Positive outlier districts used both rich assessments and a range of data and evidence to improve practice, not to punish students or teachers. In these districts, formative assessments informed instruction and helped teachers tailor supports to individual student needs. A range of data about student learning in relation to teaching practice allowed teachers and leaders to monitor the effectiveness of programs and interventions and continuously improve.

State and federal policymakers both have a role to play in developing productive assessments and appropriate uses of data. Federal policy should incentivize the development of performance-based assessments that can better reflect and measure deeper learning. This can be accomplished through both funding for assessment development and the use of appropriate standards for approving state plans. States can select and develop assessments that measure higher-order skills and support districts in using them, along with an array of data to support student learning. California has moved in this direction with the adoption of the Smarter Balanced assessments (now named the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress), emphasizing advanced competencies such as critical thinking, the adoption of a multiple measures dashboard, and the Local Control Accountability Plan process. States can augment these with school climate surveys for students, staff, and families to inform school and district improvement efforts and triangulate with other data.

Districts and schools can use these assessment tools, analysis of student work, survey data, and other indicators—such as attendance rates, suspensions, and evidence of student needs—to improve school climate, to shape teaching and learning, and to identify and address student needs. Districts can support schools and teachers with professional learning and establish structures for data to be analyzed and used effectively in continuous improvement cycles at district and school levels.

4. Create coherent systems of support based on student needs, including academic, social, and emotional learning.

Positive outlier districts created systems of support for students, tailored to their specific needs. Consistent with research in the science of learning and development, these supports incorporated both academic and social and emotional learning supports and were increasingly framed as multi-tiered systems of support.Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791. Social and emotional supports included social-emotional learning programs; wraparound services for health, mental health, and social supports; strategies such as culturally responsive teaching and learning; trauma-informed teaching and restorative justice practices; and parent engagement strategies to support student learning in and beyond school.

Federal and state policymakers can support these practices by coordinating agencies, programs, and funding to provide more streamlined and better integrated services to children to support their physical and mental health and welfare, as well as their academic, social, and emotional learning. They can also invest in the training of educators and associated professionals so that they can develop practices and systems focused on the needs of the whole child, while ensuring that resources for developing effective programs for English learners, students with disabilities, children who are homeless or in foster care, and others with particular needs are readily available.

Districts can implement multi-tiered systems of support as a core strategy to meet all students’ academic, social, and emotional needs, and foster inclusive student assignment policies. They can also increase support for both specialized and integrated English Language Development in mainstream classes. Districts can support programs to engage parents as partners in student learning.

5. Allocate resources for equity.

Positive outlier districts consciously allocated resources to meet a wide range of diverse pupil needs for additional supports. They also invested in an experienced, stable educator workforce and in professional learning to enable that workforce to become highly expert in meeting all students’ needs.

Federal policymakers can encourage these practices by enforcing equity provisions in federal laws, such as the Every Student Succeeds Act, that require equitable distributions of resources and staff. State policymakers should allocate funds based on pupil needs and, when making investments, take into account the need for increasingly well-prepared educators and a wide range of wraparound services and integrated student supports. California’s LCFF was designed for greater equity, providing additional funds to support districts with concentrations of students living in poverty, English learners, and those in foster care. Through the state’s Local Control Accountability Plan, the state has also set expectations that districts will allocate funds internally to meet the needs of historically underserved students.

Districts should also focus on resource adequacy and equity—not only in how they allocate funds to school sites and programs, but also in how they build and resource supports for struggling students. In particular, districts can spend funds efficiently when they invest in expert teachers who are assigned to teach students with greater needs and to mentor the teachers in those contexts, when they design and fund effective programs for those students, and when they intervene early and effectively for students who may struggle.

A goal of school reform and improvement is to increase the number of districts succeeding in educating all students well. This requires not only focused work on the part of schools and districts, but supportive policy environments that enable that work to be productive and widespread. This report offers some insights to develop policies and practices that can support deeper learning and equity from the statehouse to the schoolhouse.

Closing the Opportunity Gap: How Positive Outlier Districts in California Are Pursuing Equitable Access to Deeper Learning by Dion Burns, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Catilin Scott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this project and the deeper learning work of the Learning Policy Institute has been provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Sandler Family Foundation.

Photos provided with permission by Chula Vista Elementary School District, Clovis Unified School District, Gridley Unified School District, Hawthorne School District, Long Beach Unified School District, Sanger Unified School District, and San Diego Unified School District.