In Debt: Student Loan Burdens Among Teachers

Summary

Efforts to build a well-prepared, stable, and diverse teacher workforce can face many challenges; these include lower compensation than comparable college-degree careers and high costs of credentialing. More than 6 in 10 teachers have taken out student loans to support their education, and close to 4 in 10 are still repaying them. Student loan borrowing and repayment rates are highest among beginning teachers, special education teachers, and Black teachers. These loans require many teachers to take second jobs and result in high levels of loan-related stress. Student loan burdens may contribute to teacher shortages and influence the workforce composition: They can disincentivize entry into the profession, dissuade teachers from seeking additional certification, or affect teachers’ decisions to stay. Policies to address teachers’ student loan burdens include expanding service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs; expanding affordability and availability of high-retention preparation pathways; increasing total compensation; and underwriting the costs of earning high-need, advanced credentials.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

Recruiting and retaining a well-prepared, stable, and diverse teacher workforce is a critical endeavor to advance student learning and development. However, persistent teacher shortages across the nation’s schools—influenced by the quality and affordability of teacher preparation and credentialing, job-related stress, and compensation—hamper this mission. The student loan debt incurred to become and stay a teacher is intertwined with these factors, as suggested by prior research.

In 2023, teachers’ average salaries were 26.6% lower than salaries for other college graduates.The estimate compares salaries for teachers with salaries of other professions that require equivalent levels of educational attainment. When student loan repayments are layered on top of lower salaries, they further reduce teachers’ income that can go toward living costs, family expenses, or saving. For some teacher candidates, the prospect of accumulating student loans could deter them from pursuing high-quality comprehensive preservice preparation; these programs may take longer to complete and thus typically cost more than shorter and often less-rigorous programs that bypass extensive clinical practice and integrated coursework. For other potential candidates, student loan debt may dissuade them from pursuing teaching as a career altogether. For current teachers, student loans and debt repayment could discourage them from earning advanced degrees or credentials and add to their job-related stress.Chapman, B., & Lounkaew, K. (2015). An analysis of Stafford loan repayment burdens. Economics of Education Review, 45, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.11.003; Rothstein, J., & Rouse, C. E. (2011). Constrained after college: Student loans and early-career occupational choices. Journal of Public Economics, 95(1–2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.09.015

Accordingly, the current state of teaching and the continued need to support a well-prepared, diverse, and stable profession underscore the importance of assessing how student loans impact teachers, especially given the investments required to become and stay a teacher. First, nearly all states require that teachers have a bachelor’s degree to earn a standard initial teaching license, and most states require teacher candidates to complete an approved teacher preparation program. A large and rising percentage of teacher candidates and public school teachers are obtaining master’s or other advanced degrees, and higher degrees or additional credentials are increasingly common for career advancement.

Second, these investments have become increasingly expensive. The costs of postsecondary education have grown by close to 50% over the past 2 decades. While there are some supports from the federal government to defray these costs—including the Public Service Loan Forgiveness, Teacher Loan Forgiveness, and TEACH grant service scholarship programs—they are not enough to offset them. As a result, teacher candidates and teachers may seek out external sources of aid, such as student loans. Indeed, the average amount owed in loans among those who completed an education program in 2020 and took out student loans was $29,250 for a bachelor’s degree, $38,230 for a master’s degree, and $42,480 for any post-baccalaureate degree (i.e., a master’s or doctorate degree or post-baccalaureate certificate programs).Amount owed is based on the principal balance (excluding interest) and was calculated only for degree completers who had outstanding loans. Data include federal and private student loans. See U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2020 Undergraduate Students (NPSAS:UG); U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2020 Graduate Students (NPSAS:GR). Data can be retrieved on NCES’s DataLab using codes lhbxpo and nixwab.

The landscape for student loan borrowers has continuously shifted over the last several years. These shifts included the student loan payment moratorium established in response to the pandemic and an October 2024 ending of protections that shielded borrowers from the harshest consequences when missing payments, among others. Altogether, these changes have resurfaced the need for policy action to address student loan debt and the impacts the debt can have on the teaching profession. The strains arising from student loans could pose additional challenges for teachers as well as for policymakers and school leaders who want to support a highly qualified, stable, and diverse teaching workforce. As such, it is important to understand the landscape and the implications of student loan debt among the teaching workforce and to outline recommendations for alleviating these debt burdens.

This brief describes the state of student loan borrowing and repayment among full-time public school teachers who have at least a bachelor’s degree, using data from the 2020–21 National Teacher and Principal Survey.The data are nationally representative and provided by the National Center for Education Statistics. More details on methodology are described in the report’s Technical Appendix. Using analyses of this survey, the brief discusses how student loan burdens differ by teacher characteristics and the extent to which student loan borrowing and debt is associated with teachers’ employment decisions and well-being. The brief concludes with policy recommendations.

Student Loan Borrowing and Repayment Among Teachers

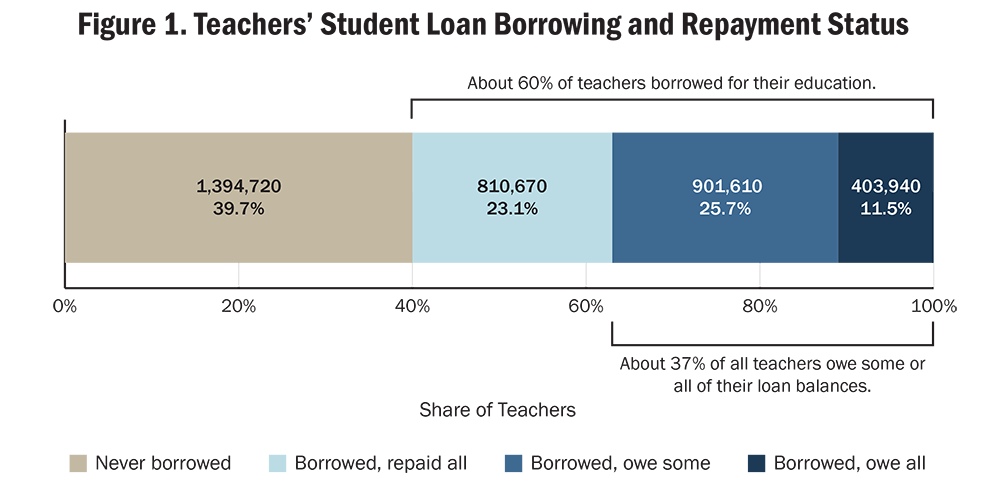

About 60% of teachers borrowed for their education, representing about 2.1 million teachers. This included 55.5% of teachers with a bachelor’s degree and 63.2% of teachers with a master’s degree. Data from another national survey of recent graduates show that those who majored in education had borrowing rates at least 10 percentage points higher than graduates as a whole, at both the bachelor’s and master’s degree levels.Specifically, 75.9% of bachelor’s degree holders and 76.4% of master’s degree holders who majored in education have borrowed, compared to 60.8% and 66.2% of all program completers in any major at the bachelor’s and master’s levels, respectively. For additional context, not all education majors end up pursuing a teaching career, and not all teachers enter the profession after completing an education major. See U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2020 Undergraduate Students (NPSAS:UG); U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2020 Graduate Students (NPSAS:GR). Data can be retrieved on NCES’s DataLab using codes uilktf and zvphtk.

About 37% of all teachers, or about 1.3 million teachers, are still repaying their student loans. Nearly one third of these teachers—totaling more than 400,000—still owe their full balance, as shown in Figure 1. On average, teachers repaying their student loans reported paying $342 a month, which exceeds the amount the typical borrower pays toward their student loans monthly ($200–$299).

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of the National Teacher and Principal Survey, 2020–21. (2023).

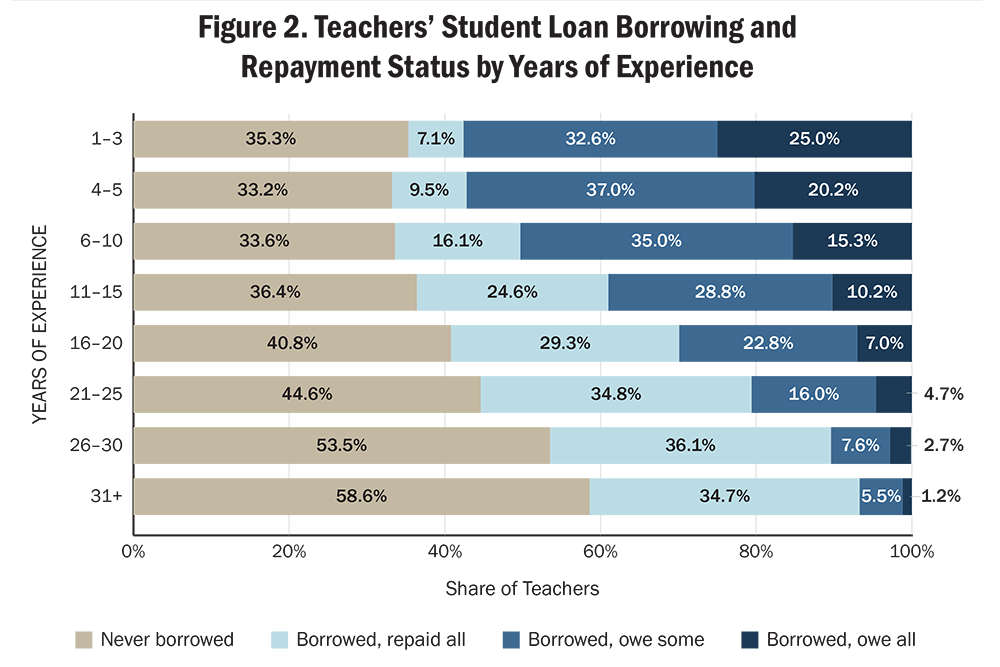

The portion of teachers who carry loan balances decreases as teachers have more years of teaching experience. This could be expected given the typical timing and structure of student loans and teachers’ ability to repay over time. Still, a sizeable portion of teachers carry loan debt well into their careers. For example, as illustrated in Figure 2, close to 3 of every 10 teachers with 16–20 years of experience are still repaying some or all of their loans. This is despite the fact that these teachers can typically benefit from the Teacher Loan Forgiveness program (up to $17,500 in forgiveness after 5 years of consecutive service) or the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (full forgiveness after 10 years of service) with that level of experience. This could signal potential barriers in information about or access to these programs.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of the National Teacher and Principal Survey, 2020–21. (2023).

Student loan debt affects all groups of teachers, but beginning teachers, special education teachers, and Black teachers have taken out student loans and owe payments at higher rates.

Student loan borrowing is especially acute for newer teachers: Around 65% of teachers in their first 10 years of teaching have ever taken out loans, compared to about 41% of teachers with more than 30 years of experience. The growing reliance on loans aligns with overall trends in student loan borrowing rates over time and may reflect the rising costs of preparation and credentialing.

Special education teachers, compared to teachers of other subject areas, are most likely to have ever taken out student loans (65.2%) and to owe their entire balance (15.4%).See Appendix Table A2 in the report for more details on the variation in the rates of student loan borrowing and repayment by field of main teaching assignment. Generally, special education teachers obtain a master’s degree, advanced certificates, or additional training for specializations after they earn their bachelor’s degree and licensure. These may contribute to higher costs and greater loan debt to teach in an area that is facing one of the most intense shortages nationwide.

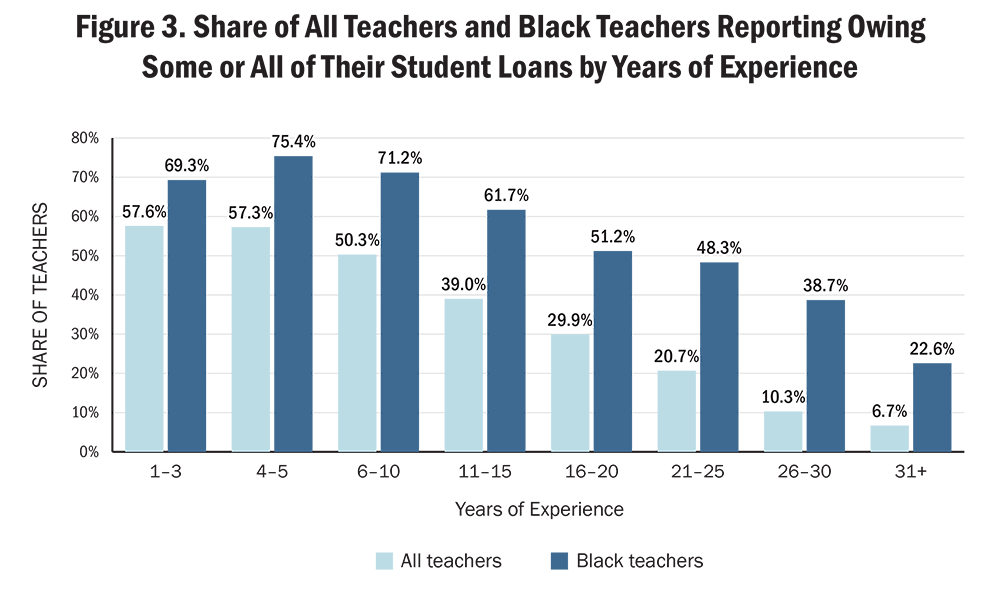

Relative to other racial and ethnic groups studied, Black teachers borrow and owe on their student loans at the highest rates, with about 71% of Black teachers having ever taken out student loans and almost 60% of all Black teachers still in repayment. Moreover, 31.4% of all Black teachers still owe their entire balance—close to 3 times larger than the share of all teachers who owe their full balance (11.5%; see Figure 1). These disparities hold true for teachers with more years of experience, as shown in Figure 3, as well as across levels of educational attainment. They also signal potential systemic barriers that make Black teachers more reliant on student loans and more likely to hold debt throughout their teaching careers.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of the National Teacher and Principal Survey, 2020–21. (2023).

Consequences on Teachers’ Employment and Well-Being

More than one third of teachers who borrowed for their education work multiple jobs because of their student loan debt. This represents about 22.1% of all teachers. The share of teachers working multiple jobs is larger among those who have larger repayment bills.

Most teachers with outstanding student loans—about 6 in 10—report high or very high levels of stress due to their student loan debt. This represents about 22.4% of all teachers. Student loan-related stress is correlated with overall job-related stress: Teachers with very high loan-related stress levels were nearly twice as likely to report feeling stressed and disappointed with their jobs compared to teachers with very low to moderate loan-related stress levels.

Policy Recommendations

In order to build and maintain a well-prepared, stable, and diverse teacher workforce, it is important to reduce the barriers related to entering and staying in the profession. The consequences of student loan borrowing and repayment could contribute to already challenging working conditions in the profession, which in turn can influence attrition and teacher shortages. Reducing debt burdens could influence who enters and stays in the profession, their preparation experiences, and their stress levels and satisfaction while teaching. There are multiple policy approaches that could reduce student loan debt and the barriers it poses for prospective and current teachers. With over 90% of outstanding student loans being administered or held by the U.S. Department of Education, the federal government is in a particularly strong position to directly address teachers’ loan-induced financial strains. Accordingly, the recommendations primarily focus on federal levers, many of which can be supported with state and local action. Most of the strategies address the financial strains associated with student loans while also strengthening teacher recruitment and retention.

-

Expand service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs. Service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs provide financial support to teachers in return for a service commitment (e.g., working in a high-need school for a certain number of years). Service scholarships provide upfront aid that reduces or eliminates the need to borrow, while loan forgiveness programs cancel accrued loan debt. Both programs aid in teacher recruitment and retention when they meaningfully offset the cost of a teacher’s preparation, are well-designed, and are administered competently.Podolsky, A., & Kini, T. (2016). How effective are loan forgiveness and service scholarships for recruiting teachers? [Policy brief]. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/how-effective-are-loan-forgiveness-and-service-scholarships-recruiting-teachers; Steele, J., Murnane, R., & Willett, J. (2010). Do financial incentives help low-performing schools attract and keep academically talented teachers? Evidence from California. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(3), 451–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20505 These programs could be expanded and improved upon, including their administration, to alleviate the student loan burdens teacher candidates and teachers face.

-

Increase service scholarships award amounts and improve the programs’ administration. Federally, the TEACH grant offers up to $4,000 per year in grant aid to postsecondary students who commit to teaching a high-need subject for 4 years in a school that serves students from low-income backgrounds. However, this grant amount has not increased since its initial authorization in 2007, despite the increasing costs of preparation and credentialing.Instead, the program has been cut by, on average, roughly $225 annually since 2013 due to automatic spending cuts required by the Budget Control Act of 2011. The maximum award for FY24 is $3,772. Cuts will continue through FY2029 absent congressional action. See Federal Student Aid. (n.d.). Receive a TEACH Grant to pay for college. https://studentaid.gov/understand-aid/types/grants/teach; Congressional Research Service. (2019). The Budget Control Act: Frequently asked questions. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44874.pdf The grant can also convert to a loan with backdated interest if teachers do not complete the 4-year service commitment. To align the TEACH grant program with the research on effective service scholarships and the current costs of higher education, Congress could increase the grant award, reform the loan conversion penalty, and allow early childhood educators (who are not currently completely covered) to be eligible for benefits.Darling-Hammond, L., DiNapoli, M. A., Jr., & Kini, T. (2023). The federal role in ending teacher shortages. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/649.892

-

Make federal student loan payments for teachers until they are eligible for forgiveness. Federal loan forgiveness programs for teachers, primarily the Teacher Loan Forgiveness (TLF) and Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) programs, relieve some or all of teachers’ outstanding student loan balances after the fulfillment of a service requirement. However, these programs require teachers to shoulder monthly payments for years with salaries that are lower than those of similarly educated professionals, especially in the first few years of teaching.For teacher salaries relative to other college educated professionals, see Allegretto, S. (2024). Teacher pay rises in 2023—but not enough to shrink pay gap with other college graduates. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/teacher-pay-in-2023/. For starting salaries for teachers and their variation across states, see Learning Policy Institute. (2023). The state of the teacher workforce: A state-by-state analysis of the factors influencing teacher shortages, supply, demand, and equity [Interactive map]. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/state-of-teacher-workforce-interactive The federal government could make the monthly student loan payments on behalf of public school teachers while they are teaching and ensure the debt is retired after 10 years of service—an incentive for both recruitment and retention. The federal government could provide even more support to teachers working in high-need schools and in early childhood education (who are not always eligible), where salaries are generally lower, by not only covering their monthly federal student loan payments for as long as they are teaching but also speeding up the time it takes for their debt to be forgiven (for example, to 5 years of service).This can be accomplished through congressional action, such as the Loan Forgiveness for Educators Act, as well as executive action by the U.S. Department of Education. For more details, see Loan Forgiveness for Educators Act. S. 963. 118th Congr. (2023). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/963; Darling-Hammond, L., DiNapoli, M. A., Jr., & Kini, T. (2023). The federal role in ending teacher shortages. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/649.892

-

In addition to federal programs, multiple states offer educator loan repayment programs in which the state directly pays teachers’ student loan providers, as well as state-specific service scholarships to support teacher candidates.For state examples of loan forgiveness programs, see Delaware and Illinois; for state examples of service scholarship programs, see California’s Golden State Teacher Grant Program and North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program. These types of state programs can complement federal loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs.

-

Expand the affordability and availability of high-retention preparation pathways. Some high-retention pathways into teaching, such as residency programs and some Grow Your Own programs, offer high-quality preparation along with financial support. These types of programs often underwrite all or most of the cost of teacher preparation and provide stipends in exchange for a service commitment. Some residency programs also subsidize the costs of tuition, lowering the overall costs for candidates.Fitz, J., & Yun, C. (2024). Successful teacher residencies: What matters and what works [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/successful-teacher-residencies-brief; Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Learning Policy Institute. These financial supports can reduce or eliminate the need to borrow. Such programs have been found to improve teacher retention, boost teacher effectiveness, address high-need subject area shortages, and help diversify the teacher pipeline.Azar, T., Hines, E., & Scheib, C. (2020). Teacher residencies as a vehicle to recruit teachers of color. National Center for Teacher Residencies; Papay, J. P., West, M. R., Fullerton, J. B., & Kane, T. J. (2012). Does an urban teacher residency increase student achievement? Early evidence from Boston. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(4), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373712454328

-

Increase funding for programs that support high-retention pathways. At the federal level, programs that fund high-retention pathways into teaching, including the Teacher Quality Partnership, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Part D Personnel Preparation, and Augustus F. Hawkins Center of Excellence programs, have been chronically underfunded. The federal government could provide robust and sustained funding to these programs and leverage such increases to support state capacity to grow high-retention pathways with federal seed or matching funds.

-

-

Increase teachers’ total compensation to bolster teachers’ capacity to repay their student loans. Outstanding student loan debt is relatively more burdensome for teachers than for other college graduates because teacher salaries are relatively lower. This debt can affect the recruitment of new teachers, where teachers decide to teach, and the likelihood that teachers remain in the classroom.Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/454.278; Sherratt, E., Lachlan, L., & Alavi, K. (2023). Raising the bar on teacher pay. Center on Great Teachers and Leaders at American Institutes for Research and the Teacher Salary Project. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/Raising_the_Bar_on_Teacher_Pay.pdf

-

Raise teachers’ salaries. Raising teachers’ total compensation would reduce the financial strains teachers experience, not only from student loan repayment obligations but also from other expenses such as housing and child care costs. State and local education agency actions to raise and equalize salaries can help increase teachers’ ability to contribute toward their student loan repayments, savings, or other expenses. For example, some states—including Maryland, New Mexico, and Tennessee—have enacted salary equalizations and raises through legislation. Various governors have also recently committed to raising teacher pay.

-

Bolster teachers’ net compensation through tax credits and housing subsidies. These non-salary supports can also increase teachers’ total compensation. A federal and/or state refundable tax credit for educators could be designed to incentivize service in high-need areas, where there are fewer state and local resources than in wealthier areas and salaries are lower.Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2011). Speaking of salaries: What it will take to get qualified, effective teachers in all communities. Center for American Progress. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED536080; Benner, M., Roth, E., Johnson, S., & Bahn, K. (2018). How to give teachers a $10,000 raise. Center for American Progress; Darling-Hammond, L., DiNapoli, M. A., Jr., & Kini, T. (2023). The federal role in ending teacher shortages. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/649.892; Partnership for the Future of Learning. (2021). Competitive and equitable compensation. In Teaching Profession Playbook. https://www.teachingplaybook.org/digital/chapter-5-compensation For example, such a program could provide tax credits on a sliding scale to give the largest credit to teachers working in schools classified as having the highest need.

-

In addition, policymakers in federal, state, and local governments could provide housing support and other subsidies to educators, especially in areas where housing options are limited or expensive, further straining teachers’ lower salaries. The federal government could make existing housing subsidies more readily available and offer additional housing supports through down payment assistance, low- or no-interest home loans, or support for governmental entities to build or purchase affordable housing for teachers. Some states and districts have taken steps to lower housing costs and expand these incentives.

-

Incentivize and underwrite the costs of earning high-need, advanced credentials, which may help avoid additional debt, improve compensation, and enhance teacher satisfaction and retention. Ensuring that teachers can access high-need, advanced credentials—such as obtaining additional certification in special education or bilingual education or pursuing National Board Certification—often offers them an opportunity to increase their income by moving to a higher pay scale without having to go further into debt.

-

Underwrite coursework and certification costs to help teachers earn high-need credentials. These investments, which can be made by federal, state, or local governments, not only lift the burden of additional financial strain from individual teachers but also allow schools to build on the expertise of current teachers, both of which serve as effective retention strategies. These investments could encourage teachers to earn subject matter credentials that are in high demand, such as those for special education, bilingual education, math, and science, adding value to schools’ abilities to meet student needs while increasing compensation on most salary schedules at the same time.

-

Provide support for advanced credentials, such as National Board Certification. States and districts can provide financial incentives to train and support teachers to become National Board certified by underwriting certification costs. Teachers who are National Board certified have been found to be highly effective as teachers, mentors, and colleagues, raising both the level of practice and student outcomes. Many states offer support to pay for, award annual stipends for, or raise salaries for National Board Certification, with greater incentives for those who work in high-need schools—providing stability and mentoring for new teachers in those schools while retaining accomplished teachers as well.

-

In Debt: Student Loan Burdens Among Teachers (brief) by Wesley Wei, Emma García, Michael A. DiNapoli Jr., Susan Kemper Patrick, and Melanie Leung-Gagné is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.