Cultivating Relationships in Secondary Classrooms: Practices That Matter

Summary

The science of learning and development demonstrates that when young people maintain positive school-based relationships, their learning and well-being is supported and enhanced. This brief elevates the practices and approaches that secondary school educators and staff can use to put relationships and caring at the center of their practice. It describes personalization tools and practices that can cultivate positive student–teacher relationships and empathy-building. It also highlights approaches that school adults can use to promote a sense of safety and belonging, including practices that foster community-building, restorative approaches to conflict resolution, identity safety, student agency, and social and emotional wellness. The practices in this brief are vital to cultivating personalized and trustful relationships. When coupled with the school-level structures described in the companion brief, Cultivating Relationships in Secondary Schools: Structures That Matter, these relationship-centered practices can optimize student learning, well-being, and agency.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Relationships Support Learning and Development

Research on the science of learning and development demonstrates that when young people maintain positive school-based relationships, their learning and well-being is supported and enhanced. While true for all young people, positive relationships are especially crucial for young people experiencing the effects of poverty, trauma, and discrimination, which can inhibit relationships and trust-building with school adults. In addition, being connected to one or more caring adults is of particular importance for middle schoolers and high schoolers, who increasingly seek a sense of belonging as they explore their unique and multifaceted identities and interests.

While studies indicate that positive connections enable youth learning and development, secondary learning environments often make it difficult for students and school adults to build relationships. For instance, school schedules may make it so that students see seven or eight teachers a day for 45- or 50-minute intervals, while their teachers see more than 150 students on a daily basis. Schedules like these make it challenging for educators to know each student well, despite their best efforts.

How Relationships Support Learning and Development

Positive and caring relationships, when central features of a school, support student learning and development in multiple ways. Research suggests that relationship-centered schools:

- are rich in protective factors that help reduce anxiety and stress among students;

- support social and emotional development, which can bolster student engagement, motivation, healthy attachment, and a sense of school connectedness;

- allow students to explore new learning experiences and develop their multifaceted identities; and

- pave the way for improvements in student outcomes such as academic achievement and graduation rates.

Beyond the important impact that relationships can have on individual students, attention to relationship-building in schools can create a ripple effect that contributes to the development of a positive school culture and climate.

Source: Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140.

The research brief Cultivating Relationships in Secondary Schools: Structures That Matter illustrates how secondary schools can institute structures such as small learning communities, cohorts, advisory systems, and looping that provide greater opportunities for students and school adults to develop caring and supportive connections. However, having relationship-centered structures in place does not guarantee that positive relationships between youth and school adults will develop. The relationship-building practices that educators use within those structures are key to fully realizing the promise of positive relationships to support learning and development.

This brief elevates activities and approaches that school adults can use to put relationships and caring at the center of their practice. Drawing upon Design Principles for Schools: Putting the Science of Learning and Development Into Action, the brief describes personalization tools and practices that can cultivate positive student–teacher relationships and empathy-building. It also highlights approaches that school adults can use to promote a sense of safety and belonging, including practices that foster community-building, restorative approaches to conflict resolution, identity safety, student agency, and social and emotional wellness.

Practices That Personalize Relationships

Individual connections between students and school adults are at the core of relationship-centered schooling. Secondary school teachers and staff can incorporate a range of everyday practices and tools to enhance their relationships with students and support student learning.

Daily Practices for Personalization

When implemented consistently, several classroom routines can deepen relationships between students and teachers. For example:

- Everyday routines, like greeting students as they arrive to class or holding short conferences throughout instructional or advisory periods, help teachers to connect with students and understand their progress. Maintaining an open-door policy and holding weekly office hours, where students are able to connect with staff during lunch periods or after school, also invite students to have conversations with educators and staff. These practices make young people feel valued by school staff and reinforce that their teachers care about their growth and success in the future.

- Active listening and question posing can be practiced by educators and staff, where they encourage students to share their beliefs, interests, and experiences. In this way, teachers can better understand what students bring to the learning setting, which serves as a foundation for building knowledge. Students thrive when their interactions with adults are consistently characterized by interest and inquiry.

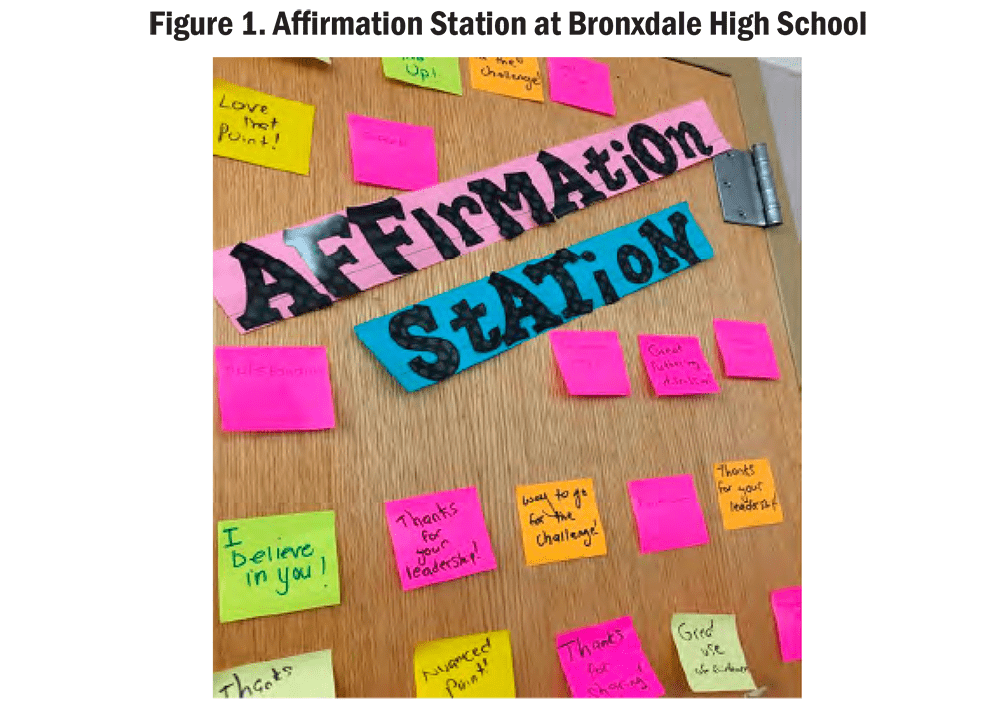

- Expressing authentic affirmation, such as “I believe in you” or “Thanks for sharing,” conveys care and respect and can boost students’ success and sense of connection. Affirmations may be shared in individual interactions between students and staff and reflected in the physical classroom environment. For example, staff at Bronxdale High School in New York City developed the “Affirmation Station” as a living forum in which sticky notes are used to express appreciation and support for students. (See Figure 1.) School staff can extend these practices by inviting youth to discuss their challenges, doubts, and worries in order to normalize the feelings and experiences that accompany adolescent development and encourage problem-solving.

The tenor and authenticity of the implementation of these personalizing practices matter for their impact. They are most effective when they lead to trustful, respectful, and reciprocal interactions that help students’ cognitive, social, and emotional capabilities and cultivate a positive self-concept.

Developing Personalized Relationships in Action

Educators and staff at Social Justice Humanitas Academy, a public high school in the Greater Los Angeles area, institute a number of daily practices and routines that allow them to regularly check in and connect with students. For example, then Principal Jeff Austin and Assistant Principal Marike Aguilar stand in front of the school each morning to greet students as they arrive, and teachers stand at the door of their classrooms to welcome students with high-fives, a smile, or other simple gestures of acknowledgment. In addition, administrators and counselors have an open-door policy and invite students to visit them when they are struggling with difficult issues.

These intentional routines provide staff with an opportunity to connect with students, see how students are doing, and communicate to students that their presence is valued. Students explained that they appreciated this collection of practices, and they valued knowing that their teachers care about their growth and success in the future. Students also reported that their teachers were responsive to their questions and messages and that they felt comfortable reaching out to their teachers for support, signaling that strong reciprocal relationships had been built.

Source: Saunders, M., Martínez, L., Flook, L., & Hernández, L. E. (2021). Social Justice Humanitas Academy:

A community school approach to whole child education. Learning Policy Institute.

Empathy-Building Tools

Practices that build empathy between students and school adults can positively impact relationship development. Research shows that empathy-building tools are powerful not only for the similarities between students and practitioners they surface, but also for “sidelining” bias and building transformative relationships. Tools that support empathy-building include:

- “Getting to Know You” Surveys. Administered at the beginning of the year, these surveys can include questions about students’ families, interests, hobbies, goals, and educational strengths. In one study, students and teachers who learned about their commonalities reported more positive relationships with each other. Students in that study also earned higher grades when teachers learned what they had in common, and achievement gap disparities for Black and Latinx students closed by more than 60%.

- Empathy Interviews. These one-on-one conversations between and among students and teachers use open-ended questions to surface insights into specific experiences that help uncover ongoing needs and challenges. Interviewers tailor four to eight open-ended questions to the purpose of the interaction, which can range from identifying challenges in schools and classrooms to brainstorming ideas for change. These questions include probes like “Tell me more” or “Why” to elicit the experiences and points of view of the interviewees. Each person engaged in the empathy interview is both an interviewee and an interviewer, enabling each individual to share their perspective and to understand the point of view of the other.

These and similar tools communicate care, interest, and appreciation for student experiences. They facilitate personal interactions between students and teachers and can help to illuminate and mitigate biases that impede relationship-building, often with tangible results on achievement.

Learning to Engage in Empathy Interviews

School leaders and teachers in the Long Beach Unified School District in California use empathy interviews as part of their effort to become a “relationship-centered district.” Practitioners are introduced to these relationship-building approaches during Learning Days—a voluntary professional development opportunity that gathers high school students and adults to learn together about the challenges and opportunities in the district.

During a Learning Day in February 2020, student facilitators introduced attendees to the practice of empathy interviews. Youth facilitators began the discussion of empathy interviews by describing their goals and the following norms to support their effective implementation:

- Be curious and take a learning stance.

- Listen more than you speak.

- Be fully present, without distractions.

- Do not challenge, correct, or interrupt.

- Express gratitude.

After this introduction, Learning Day attendees engaged in a fishbowl activity to witness the practice in action. They broke into small groups of 10–12 individuals and observed one educator and one student engage in an empathy interview guided by questions like:

- Talk to us about your experience at your school. What is your vision for student success at the school?

- What do you think it is going to take to transform your school into a relationship-centered school?

- What do you wish you knew more about, had more training on, or had more resources for in order to collaborate with students?

- What is your biggest hope for collaboration between staff and students at your school?

After a 10-minute exchange between the educator and student, observers were invited to pose questions about the empathy interview process—to inquire about the interview that just transpired as well as the processes that enable these conversations to be integrated into ongoing practice.

Source: Hernández, L. E., & Rivero, E. (2024). Striving for relationship-centered schools: Insights from a community-based transformation campaign. Learning Policy Institute.

Practices That Promote Safety and Belonging

Fostering a sense of safety and belonging within each and every student is also an essential component of relationship-centered practice. As educators and staff come to know students well through personalization practices, it is also important that they implement approaches that enable students’ social, emotional, and identity development to support their learning and sense of connection.

Creating a Sense of Community

Educators and staff can promote belonging and safety by intentionally building community, which can combat a sense of anonymity that many adolescents may experience in their schools. Teachers and staff can foster inclusion and community through practices such as:

- Regular community meetings to help build classroom environments where students have a sense of belonging, voice, and agency. Consistent community meetings, which can be held during advisory meetings or in regular course periods, are opportunities for students to build connections, raise issues that matter to them, and work to solve problems facing the community. They also afford opportunity to celebrate accomplishments and growth.

- Establishing shared values and norms, particularly those codeveloped with students. For example, teachers and students can establish norms of interaction for group work or develop classroom community agreements and display them in the classroom. When collaboratively developed, the practices build in student ownership and investment in classroom norms while helping students understand what is expected of them as members of the classroom community.

- Using restorative practices to address emerging problems and to repair harm. While restorative circles are a cornerstone of restorative approaches, educators and staff can use daily practices to resolve conflict in ways that sustain relationships and build community. These include the use of shared vocabulary that both staff and students can use to express feelings in a productive way. Teachers can also hold impromptu conferences during instructional time to redirect a student’s behavior with minimal disruption.

Instituting approaches and routines like these can build trust among and between students and school staff while allowing students to develop greater ownership, engagement, and responsibility in their learning settings. In addition, consistent use of these practices fosters predictability, which reduces stress and cognitive load among secondary students and thus enables greater capacity for them to engage in learning, problem-solving, and relationship-building.

Restorative Practices in the Classroom

School adults can address the challenges that emerge in secondary schools and classrooms through practices that reinforce a restorative approach to conflict resolution. This includes developing and using a shared vocabulary that students and staff can use to productively engage when confronted with a difficult situation. A common practice is the use of affective statements, which focus on the perceptions and feelings of the speaker rather than the actions or attributes of the listener. For example, instead of saying, “You are being disrespectful,” a teacher might say, “I felt hurt and disrespected when you walked out of the classroom.” This shift in language reflects a key principle of restorative approaches, which is to focus on the deed that transpired and to illuminate its felt impact rather than criticize the doer.

Another common practice is the impromptu student conference. A teacher might use an impromptu conference if she notices a student distracted by side conversations. In such an instance, a teacher could invite the student to speak privately and then ask the student restorative questions, such as, “Is there anything going on with you today that I should know about?” or “How can I support you right now?” Often, a short, impromptu conference can refocus the student without necessitating a removal from the classroom or undermining the teacher–student relationship.

Source: Klevan, S. (2021). Building a positive school climate through restorative practices. Learning Policy Institute.

Celebrating and Sustaining Student Identity and Interests

Practices that promote identity safety also foster a sense of belonging and relationship-building, as they acknowledge and build upon students’ identities and interests. Identity-safe environments reflect, respect, and celebrate different cultures, which can build student confidence and encourage a broader embrace of cultural pluralism. Teachers can integrate identity-safe approaches into their practice in several ways, including using:

- Diverse and culturally relevant content and materials during instruction so that students can relate learning to their life experiences and deepen their understanding of other cultures, histories, and communities.

- Physical spaces that reflect and embrace cultural diversity. Classroom displays should reflect cultural plurality and the diversity and history of the student population.

- Pedagogical activities that enable learning about and from students and their communities. For example, personal or community history projects allow students to explore their identities and backgrounds during academic learning.

- Community-based projects, which often begin with teachers posing a question or asking students to identify equity-focused issues impacting them and their communities. They often provide opportunities for students to propose solutions and share their learnings.

Culturally sustaining and relevant approaches help interrupt the effects of discriminatory practices that cause students to feel unwelcome and that undermine their learning and development. In this way, these approaches can pave the way for enhanced relationships, learning, and engagement.

Community-Based Projects in Action

By creating learning opportunities that allow students to explore issues of interest to them in school and community settings, Oakland High School in Oakland, CA, provides a curriculum that draws on young people’s experiences and knowledge. Instruction within the Environmental Science Academy pathway—one of the small learning communities within the school—is focused on developing young people’s leadership skills through a student-centered and culturally sustaining curriculum. As science teacher M Fields explained:

A lot of our curriculum is focused on student-centered problems and student-centered leadership opportunities to solve those problems. ... In many cases, the curriculum at Oakland High is almost written as we go, in order to address problems that are cropping up throughout the year. ... We’ll address environmental problems that crop up in our neighborhoods and in our communities.

Teachers in the Environmental Science Academy pathway also believe that their job is to be culturally responsive and help students understand themselves, what they care about, and how they can positively impact social issues that matter to them.

To achieve their pedagogical and instructional aims, Environmental Science Academy teachers prioritize project-based learning, which allows for collaborative engagement in learning as students explore a relevant question or problem. For example, the “lake class” taught by Fields is designed around the ecology of Lake Merritt, a short walk from Oakland High’s campus. In an activity made possible through a partnership with the Lake Merritt Boathouse, students embark on pontoon boats once per week to survey different areas of the lake for various water quality factors and collect samples for testing. Students then study the samples to determine the likely causes of water pollution and contaminants. After determining the pollution sources, students study potential policy interventions to address the health of their community lake. At the culmination of the class, students develop their own interventions to address water quality, which they present to a mock city board made up of local scientists, advocates, and other industry professionals.

Even as it builds science knowledge and research and writing skills, this project-based work also requires social-emotional skills and relationships, as students must work collaboratively, communicate effectively, and manage and track learning that is important enough to support the hard work and revision needed to achieve mastery. Moreover, it demonstrates how environmental science can be made relevant and culturally responsive by focusing on the environment as the space in which students live, work, and play.

Source: Adapted from Klevan, S., Daniel, J., Fehrer, K., & Maier, A. (2023). Creating the conditions for children to learn: Oakland’s districtwide community schools initiative. Learning Policy Institute.

Fostering Student Voice and Agency

Positive relationships are developmental, whereby they foster student voice and cultivate youth agency so that every student can become a confident and independent individual and advocate. Teachers can create daily opportunities for young people to grow their voice and agency. For instance, teachers can offer students choice and flexibility as they engage in intellectually demanding inquiries and help students develop strategies for monitoring and managing their own learning.

The practices described throughout this brief elevate youth voice and agency to varying degrees. Other notable opportunities for fostering youth voice and leadership in the classroom include:

- Student-led learning activities that allow students and teachers to codesign the experience and learn alongside each other. Examples include community walks that immerse teachers in students’ home environments as they educate teachers about students’ backgrounds, community, challenges, and cultural assets. Student-led learning activities can give teachers a deeper understanding of who students are and what they bring to the learning setting. This understanding, in turn, can help teachers continue to provide culturally relevant and sustaining learning experiences.

- Student-led conferences, where young people actively participate in and facilitate teacher–family discussions on their progress. Effective student-led conferences are held more frequently (e.g., 2 or 3 times per year) and at times that family members can attend. They are used as opportunities for students, families, and staff to plan together for children’s goals, rather than communicating judgments about how children are doing.

Student-Led Conferences in Action

Midway through each school year, middle schoolers and high schoolers at Gateway Public Schools in San Francisco, CA, engage in student-led conferences. During these conferences, students make presentations, share learning artifacts, and engage in discussions with their teacher and families about what they are learning and how they are doing.

Ilan, a precocious 7th-grader, led one such conference for his family members in attendance. Ilan began by welcoming his family and sharing the conference’s agenda before immediately describing how proud he was of the personal narrative essay he wrote for his humanities class. He shared:

For this project I had to analyze the text for structure, theme, tone, and character development, and then I had to use those skills to write a narrative from the first-person point of view. I’ve never done anything like this before, but I had a ton of fun. … The biggest challenge for me was the typing and the occasional writer’s block—even though I was writing from my own experience. A strategy I used to overcome this challenge was looking back at all of our old “Do Nows” when I got stuck on a scene.

As Ilan’s presentation turned to other subject areas, his parents interjected with clarifying questions and words of encouragement. When presenting his math work, Ilan candidly stated, “You all know that last year I didn’t do well. This year, I got some pullout time and extra help, and this is the best grade I’ve ever gotten in math.” Ilan’s father then said, “Ilan, congrats buddy. You have worked so hard, and I’ve seen you gain so much confidence.” The conference continued in this way as Ilan reflected on all his classes. During the goal-setting time, the presentation became a conversation in which Ilan, his parents, and his teacher together brainstormed goals for next quarter.

Overall, Gateway’s student-led conferences foster student agency and leadership and support students in taking control of their own learning, as they share their work, their progress, and their goals with both their families and teacher.

Source: Adapted from Cook-Harvey, C. M., Flook, L., Efland, E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2020). Teaching for powerful learning: Lessons from Gateway Public Schools. Learning Policy Institute.

Attending to Students’ Physical and Emotional Well-Being

Teachers in secondary schools can enhance a culture of care and connectedness through daily routines that promote student well-being. These routines include:

- Breathing or movement exercises at the beginning of class or as a break from instruction to support emotional awareness and regulation.

- Restoration spaces in classrooms where students can go to monitor or redirect their attention so they can productively engage in learning and peer collaboration.

- Mindfulness and other calming or recentering practices that focus on breathing techniques and contemplative practice.

These types of practices benefit the brain’s architecture, learning, and stress management, and they may be particularly helpful during adolescent development.

Conclusion

This brief describes practices that secondary school teachers and staff can use to build personalized, caring, and trustful relationships with students that can enable them to grow and thrive as individuals and learners. When coupled with school-level structures that create ample opportunities for positive connections between students and school adults, these relationship-centered approaches can optimize student learning, well-being, and agency.

While this brief focuses on approaches that build teacher–student relationships, practices that build personal connections among teachers and between teachers and families are also important to enhancing student achievement and healthy development. Educators and staff in relationship-centered secondary schools make a concerted effort to strengthen their connections with colleagues as they work to support student progress. Educators and staff in these schools also prioritize building relationships with families, taking strides to maintain consistent, meaningful, and culturally responsive communication with parents and guardians to form a supportive foundation for student learning and thriving.

Cultivating Relationships in Secondary Classrooms: Structures That Matter (brief) by Laura E. Hernández and Linda Darling-Hammond, with Natalie Nielson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by The California Endowment and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.